Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Slip at the Lip of the Cup

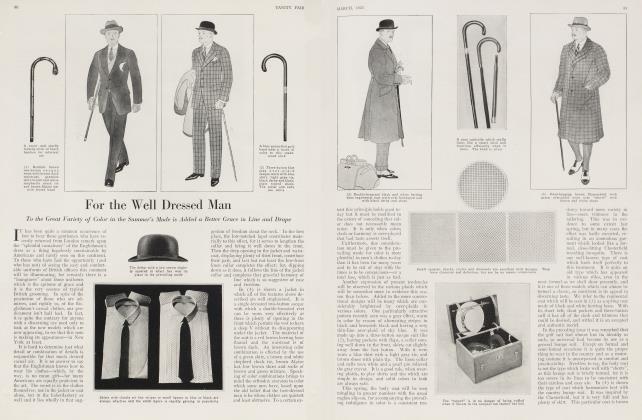

Star Golfers Have Seen Fame Disappear by the Margin of a Putt that Wouldn't Trickle In

GRANTLAND RICE

FAME, in almost every sport, is very often built upon a foundation less than an inch in width, almost as flimsy as a thin reed in a gale. Men come into a great fame that lasts for years, where a half flicker the other , way would have knocked the laurel wreath from their clammy brows to hang over the right or left ear in a sadly disorganized state.

You may or may not recall the intimate evidence connected with the case of Home-run Baker in 1911 at the Polo Grounds. Baker was facing Christy Mathewson in one of the crucial games of the world series. There were two out in the ninth inning with New York leading 1 to 0 and Baker at bat! There were two strikes and two balls on Baker when Mathewson cut the outside comer with his next pitch. For one-half second the umpire waited and then called it a ball. It was a toss-up as Mathewson still insists that the ball was over the comer. The umpire could have called it either way, as Baker stood there with his bat upon his shoulder. On the next delivered ball Baker struck off a home run that ultimately brought defeat to the Giants.

The margin between Baker striking out and Baker hitting a home run was almost as thin as air. Of such is a considerable amount of fame.

Of all games there is none where the shift of fame may spin as quickly by the turn of a ball as in golf.

While many matches are won by decisive margins, there are countless others from championship affairs to battles between enthusiastic duffers, who have never played below 100 in their careers, where the outcome is decided by this last wobble at the lip of the cup.

The Most Celebrated Case

THE most widely discussed single stroke in any amateur championship held in America was Max Marston's famous putt in 1914 against Bob Gardner.

Coming to the final tee in a 36-hole match in the semi-final round, Marston stood 1 up. A half here at the 18th hole would eliminate Gardner and send Marston into the final round against John G. Anderson.

Gardner's fine iron stopped within 8 feet of the pin while Marston reached the green some 30 feet from the cup. His approach putt was a magnificent effort, the ball curling just by the lip of the cup to stop only 20 inches below.

Quite apparently it was up to Gardner to sink his 8-footer to remain in the championship list. Gardner's putt was boldly played but the ball failed to drop. He took a step forward as if the battle were over and then decided to await the issue of Marston's final tap. The cup on this green had been placed on a slight elevation from which the grass had been worn away by constant play.

Marston's putt ran straight for the lip of the cup. Then, less than half an inch away, the roll of the ground and the grassless surface formed a combination that barely deflected the ball to one side, less than an inch out of line.

It was by the final turn of this 20-inch putt that Gardner remained in the tournament and finally won his second amateur championship. No golf match could have been decided upon a closer twist of fortune.

Mike Brady's Case

THE 120 man frequently enters the club house with his brow furrowed with care and anguish over the thought of a putt that hit the cup and jumped out, thereby costing him a golf ball and the thrill of victory. We have known such a turn to cost the depressed player over $1,000, and it is some time before his soul recovers fully from the shock.

The cost in a big championship is, of course, even higher. There is the case of Mike Brady for one notable example.

Starting the final round at Braeburn for the open championship last summer, Brady was leading Hagen by 5 strokes. Brady had slipped a trifle in his start but he had to all purposes settled down at the fourth hole. Here he had a fine, long tee shot and his second held the sloping green within 20 feet of the cup. His approach putt drifted by the rim of the cup and stopped less than 18 inches beyond where he had nothing more than a tap to get his par 4 and be under full steam again. As Brady stepped up to his ball, adjusted the club and started the head back, a big butterfly circled around and lit on the ball. Brady stopped his swing, dispersed the butterfly and became set again for another effort. But this particular butterfly was a most insistent species. It had evidently decided that the golf ball was a new white blossom, not to be so lightly given up. So again Brady found the butterfly circling around the ball in the midst of his stroke.

He stopped again. This time the butterfly was thoroughly routed, but the putt had become a different matter. There was a general feeling among the big crowd around the green that he would miss. The queer part is that Brady did not make a bad putt. He tapped the ball firmly, it started correctly, rolled a half turn out of line and after striking the rim of the cup hung on the back side.

This putt cost him the open championship, of America as he and Hagen were tied at the end of 72 holes and were forced into a play-off. This slip may have cost him even more than the one stroke for he began to worry from that point on and due largely to this worry many additional mistakes developed. It is easily conceivable that if that putt had dropped from only 18 inches away Brady would have been under full headway again with a decisive margin at the finish. At the worst he would have won by a single stroke.

The vast majority of these close turns come upon the putting green as the putt is usually the decisive stroke. The hole isn't won or lost, as a rule, until at least one putt has dropped. And most short putts that are missed are by hairbreadth margins. The final putt that Harold Hilton sank against Fred Herreshoff at Apawamis on the first extra hole barely skidded in. Hilton's short approach putt, after his ball had bounded from the big rock to the green, was three feet off line. His final effort trickled up to the cup, hung in suspense for a second and then finally curved in.

(Continued on page 114)

(Continued from page 76)

More championships have been won by this final wobble at the bare rim of the cup than you might imagine. And the number lost by the same turn has been equally great.

Off the Green

TYTOT all sudden flips from fortune or ^ misfortune develop on the green. Not all are putts. When the amateur championship was held many years ago, Walter J. Travis and Jerome D. Travers were in the thick of a nip and tuck duel. Travis stood 1 up and 2 to play. Travis, with a simple shot before him off the green, played straight for the pin. The ball was headed in the proper direction and just before reaching the green had begun to trickle slowly.

At this juncture one of the spectators decided to select a better spot to observe the putting battle that was to follow. Leaving his place in the crowd he rushed across the course at the green's edge and on his way over struck the Travis ball that was still moving with his foot. The new impetus sent the missile across a corner of the green into a deep trap, thereby wrecking the hole beyond all repair. In place of having a good chance to end the contest then and there, with a sure half in sight, Travis found the match all squared with Travers the ultimate victor.

But the true golfer rarely thinks of the long putts or the short putts that dribbled up to the cup and then barely skidded in. These are not to be counted. His main thoughts are upon those putts that ambled up to the rim and then stayed out. And as there happens to be more space outside the cup than there is inside the cup, it is only natural that more putts should stay out than drop in.

This, however, is one of those philosophical calculations about which most golfers have little time for thought.

They rarely recall the hooked drive that stopped six inches from the maw of a deep trap, replete with sand and heel prints. They rarely recall the sliced iron that started out of bounds, struck a tree or a fence and bounded back to the course. And of no consequence is the shot that stays out of the thick and waving grass by the span of a hand.

These are all natural consequences. But the putt that turns away from the cup at its final spin—the putt that doesn't go down—is a concrete example of raw injustice and only to be endured because there is nothing else to be done about it.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now