Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowOur Auction Bridge Refuge

A Sanctuary and Retreat for Persistent, Not to Say Incurable, Bridge Addicts

R. F. FOSTER

AFTER a recent duplicate match between two prominent clubs in Montclair, N. J., the hands were carefully examined by one of the officers of the losing club to determine just where the tricks went, who lost them, and how, so as to account for the difference of 1,803 points in 30 deals, the margin by which the match was lost. This is equal to about 60 points a deal, very close to the average by which the Knickerbocker team from New York won the duplicate championship at Spring Lake.

The most remarkable thing about the result of this examination was that failure to save the game, or to win the game, or to make a slam, when it was easily possible to do one or other of those things, cost the winning team 1,584 points, and the losers 3,201. The difference is 1,617, or very nearly the amount by which they lost the match.

Leibenderfer's remark, quoted in Vanity Fair for May, 1919, that eight games out of every ten are "chucked", seems still to hold true. Nothing is a surer mark of a first-class player than the way he makes or saves games. Take this distribution:

Every table in the room in a duplicate match seems to have arrived at hearts as the final declaration, and at every table A led the spade queen. Only one table out of a dozen or so won the game, making four odd, yet that result is possible against any defence. Readers of Vanity Fair are left to figure out how. The play will be given next month.

IT was to be a social progressive game, four deals at a table, and then move and change partners.

"I hope you won't have to play with him, my dear girl," remarked the widow. "You know he is not exactly a young man any more, and at the bridge table he is something fierce."

"Why, he is too much of a gentleman to say or do anything rude, I am sure."

"At a dinner or a dance, that is true; but when he sits down to play cards he is like another person. He is what they call a fan, which means a fanatic, I believe. He gets so excited if anything goes wrong, glares at his partner and shakes his head, and goes on like a wild man if his partner does not see through the back of his cards."

"You astonish me."

"Well, my dear girl," tapping her lightly with her fan, "I can only hope that you do not have to play with him, because you made such a good impression on him at Mrs. Densmore's dinner, and he's a very good catch, you know."

There were only two more progressions to make, when the girl saw that her friend the fan was taking his place at the next table but one. An instant's reflection told her that if they both won, they would meet as partners at the intervening table for the last round. The way out of that was simple; she would throw the game to her opponents, so as to be sure to lose, and stay where she was. Then the dreaded meeting would be impossible, and the game would be over.

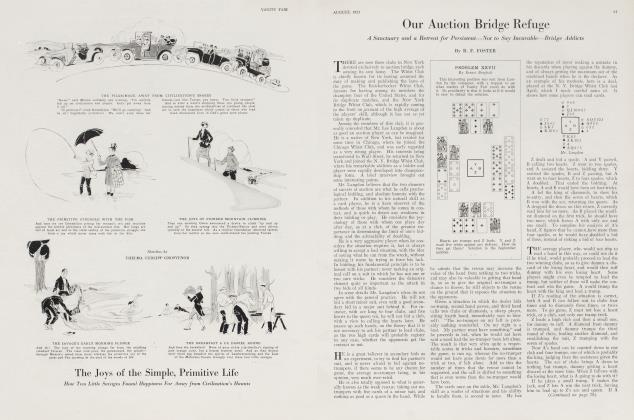

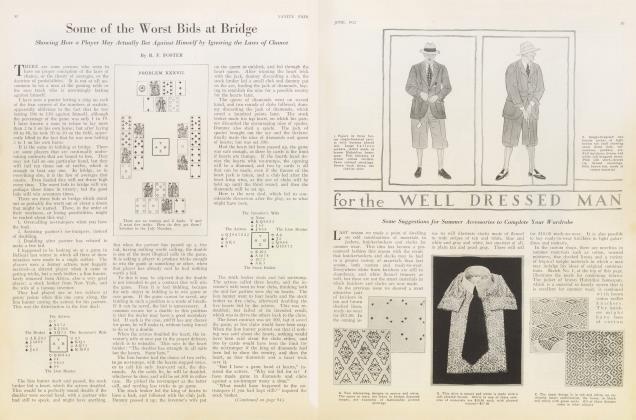

Problem XI

This is one of S. C. Kinsey's instructive seven-card endings, which show how to' pick up just one more trick than there is in sight.

There are no trumps and Z leads. Y and Z want six tricks against any defence. How do they get them?

The answer to the February problem will be found on page 108.

But, unfortunately for her plan, she had a partner who held wonderful cards, and added some twelve hundred points to their score. It seemed the hand of fate.

The fan was all smiles. He had a big score.

"I hear you are quite an expert," he told her, as he pushed the chair under her. "This is the last round, I believe. Who are our adversaries? Oh! Mrs. Chandler. How delightful."

The hand of fate had also brought the widow to the same table. She tried to persuade the fan to take her for a partner instead of the girl; but he would not listen to it, so she allowed him to arrange her fur as she whispered to the girl, "Brace up. I have a fearful dub for a partner."

In spite of her nervous dread of making some silly mistake, such as she would never make under ordinary circumstances, all went well for three hands, the fan playing them all, thanks to the widow's tact in not overcalling any of his bids. The girl was thanking her stars that nothing had happened, and the widow was all smiles of encouragement as she cut the cards for the girl to deal the last hand. This was the distribution:

She had a tremendous score, and perhaps it would be safer to call the clubs, and then her partner would take her out and play the hand. Still being in dread of his criticism, even as dummy, she decided to bid her hand aright, no-trump, and hope he would take her out in hearts or spades; but every one passed.

The dub led the trey of hearts and dummy's cards went down. The weakness in spades was the first shock, and she was so nervous that she pulled the eight of hearts from dummy, instead of the deuce, and when the widow put on the jack, she imagined it was the king and took the trick with the ace. As she gathered the trick she realized her mistake, and got so flustered that she hardly knew what she was doing.

At first she was going to apologize on the spot, but had presence of mind enough left to pull herself together and examine the position with a view to pulling herself out, and perhaps covering up the error. A glance at the dummy showed that she dare not risk getting that hand in on the spade for the finesse in diamonds or clubs, so she led the ace and queen of diamonds right out, the dub winning the second round.

When he led another small heart, she nearly fainted, and when her lone queen held the trick she could not believe her eyes; but realized instantly that the widow must have not only unjustifiably finessed the jack on the first trick, but was holding up the king now, to help her out. The widow's partner was such a dub, he would never notice it. She was smiling her thanks in the direction of the widow when the dub blurted out, "Why I thought you had that queen, partner," at the same time showing his cards to the fan, who instantly realized what had happened, and beamed upon the girl.

"Pretty work, partner," was the encouraging comment, "pretty work."

The rest was easy, the widow, still wondering what it was all about, discarding two small spades and a club on the diamonds, so as to keep a heart to lead to her partner, with the result that the girl made a little slam.

"That's the greatest hand played in New York this winter," was the fan's remark, as he put down the score. "If he does not think his partner has the queen, he leads the spades and they save the game. You win first prize in a walk. I should be delighted to play with you agam some time," and he shook hands warmly, while the widow smiled her approval.

(Continued on page 106)

(Continued from page 77)

To this day the widow is the only person who knows that the wonderful coup was nothing but a case of nerves.

Penalties at Auction

TOURING his tour of the United States in the interests of the Red Cross, Milton Work, the author of "Auction Declarations", and chairman of the committee on laws, gave a number of entertaining lectures on various subjects connected with auction bridge.

Among these was a talk devoted especially to penalties, and the general laxity of the average player in demanding some of them, although the framers of the laws considered that all were equally important, and that auction was not auction unless the rules of the game were strictly lived up to in every respect.

As he pointed out, there are about a dozen penalties connected with the play of the cards alone, after the bidding is finished, but only three of them are ever insisted upon in the ordinary social game; two of them being penalties for failure to make the contract, the other for a revoke.

These penalties are briefly summarized in a little card printed by the U. S. Playing Card Co., of Cincinnati, which is here reproduced by their permission:

PENALTIES AT AUCTION

(Condensed from the Official Laws for 1915) (Copyright, 1916, by R. F. Foster)

1—25 points for looking at a trick turned down, or for each card looked at before the deal is complete.

2—50 points for every trick by which the contract fails, 100 if doubled, 200 if redoubled.

3—50 points for a contract fulfilled after being doubled, and 50 for each trick over the doubled contract. 100 in each case if the double has been redoubled.

4—For a bid out of turn, other than passing, opponents may demand a new deal, before they bid or pass; or they may treat the bid as void, or allow it to stand.

5—When three players have passed, any information as to previous bids may be penalized by calling a lead.

6—For a lead out of turn, declarer may call a suit, or call the card exposed. No penalty for declarer or dummy leading out of turn, but the lead cannot be taken back except at the direction of an opponent.

7—If declarer touches a card in dummy, he must play it. If dummy touches or suggests a card, he may be required to play or not to play it.

8—Exposed cards must be left on the table, face up, and subject to call. No penalty for declarer's exposing cards.

9—Revoke penalty is 100 points if made by declarer. If made by opponents, declarer may take three actual tricks, or 100 points. Dummy cannot revoke. Revoking side scores nothing but honors as held.

10—Declarer may demand highest or lowest of the suit from player correcting revoke, or call card exposed.

11—If a player says trick is already his, or draws his card toward him, his partner may be called on for his highest or lowest; or to win or lose the trick.

Nos. 2, 3, and 9, Mr. Work thinks, are about the only ones to which players pay any attention, except in clubs that make a feature of auction bridge. This is either because the average player is not aware of the existence of any such laws, or because they do not think it "nice" to enforce them.

But why should three penalities be insisted on with the utmost rigor and regularity, and the remaining eight or nine be totally disregarded? One infraction of the laws is just as bad as another, and the breach of any rule may be not only unfair but unjust to the opponents. The revoke, for which almost every player exacts his pound of flesh without the slightest compunction, seldom makes the slightest difference in the result, and might more sensibly be overlooked than almost any other error in the game; but the bid out of turn, or the reference to a previous bid, may alter the "whole swing of the hand.

Here is a curious example of the result of a player's ignorance of the rules, and the consequent injustice done to her partner; or, it might be put the other way, and say that it was the partner's ignorance of the existence of Clause j, Law 60, defining dummy's right to tell the declarer that she was entitled to a specific penalty that cost them about 500 points.

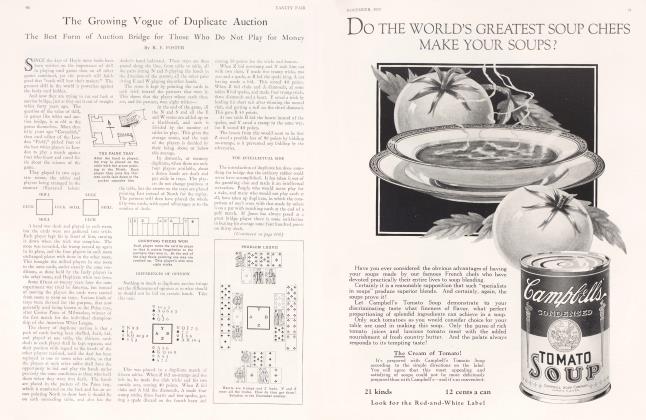

The interesting point about this hand is that the penalty allowed by the laws would have been worth something in this case, if enforced. In many hands that have come under my notice it would be inadequate. This was the distribution of the cards:

The lady who held Z's cards dealt and bid a club. A bid two hearts, and Y two spades, B and Z passing. A went to three hearts, and, Y to three spades, which B doubled, Z passing again. Instead of letting the double stand, which would have set Y for only one trick, A went to four hearts, which Y doubled, all passing.

Not wishing to lead away from the major tenace in spades and having apparently forgotten all about her partner's original bid, so much had happened since then, Y led the six of diamonds, upon which dummy put the seven and Z the trey. Looking up at her partner with astonishment before A played to the trick, Y exclaimed, "Is that the best you have? I thought you might have a trick somewhere." To this her partner replied, "I never said anything about diamonds. I bid clubs."

A was a very fine player, but evidently ignorant of the proper remedy for this offence, as she passed it without any remark. After studying the situation for a moment, she overtook dummy's seven with the ace and led the ace and queen of trumps, Y winning the second round with the king.

Taking her partner's hint, Y promptly switched to the clubs and after making two tricks in that suit, Z led the spades, trumping the third round of that suit with the six of hearts.

This gave Y and Z six tricks, and put the contract down for 300, the result being entirely due to Z's unjustifiable reference to a bid that preceded the final declaration, and which her partner had entirely forgotten in the excitement of bidding her spades against the hearts.

Under penalty No. 5, in the foregoing schedule, A had a right to call a suit, the moment either Y or Z got into the lead.

(Continued on page 108)

(Continued from page 106)

This would be when Y won the second round of trumps with the king.

By calling a diamond, dummy would have won the second round with the ten, caught Z's six of trumps with the eight, still retaining the lead, and given A three spade discards—not clubs—on the established diamond suit. Now the club ten forces Z to lose a dub trick, and A makes her contract, 64 below the line and a game won, instead of being set for 300. If a game is worth 125, this is a difference of 489.

Answer to the February Problem

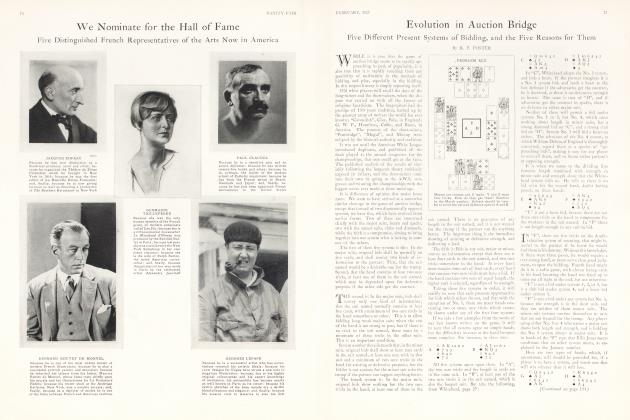

THIS was the distribution of the cards in X, which is a variation of a theme proposed by the late W. H. Whitfeld, which is to emphasize the importance of keeping as many winning cards as possible in hand until one or other of the adversaries has picked a discard.

Hearts are trumps and Z leads. Y and Z are to win every trick, against any defence. In spite of the fact that many have written to say that this is impossible, it can be done, and this is how it is managed.

In the first place, it is obvious that if Z starts with his top diamond, he forces his partner to discard at a disadvantage, because A and B can adjust their discards accordingly. On the other hand, if Z gives up his high cards in either of the shorter suits, he loses a very important reentry.

The solution, therefore, is to start with a small diamond, which Y trumps, A probably discarding a club. Now Y leads a trump, and B has to guess. If he discards a spade, Z and A will also discard spades, and Y leads a spade, which Z wins.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now