Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

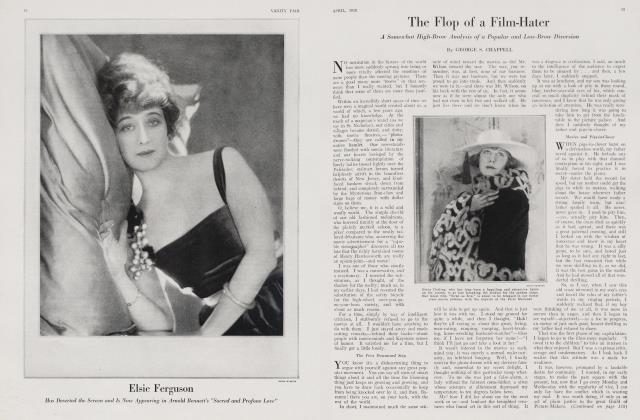

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Financial Situation

Wall Street Enters the Movies

MERRYLE STANLEY RUKEYSER

TO the cultivated person the assertion that the movies are more a business than an art will not come as a startling revelation. Yet the relatively few who are in no way associated with the industry scarcely realize perhaps what a gigantic activity it has become. Retailing movie entertainment is now yielding approximately $750,000,000 a year in receipts.

In the days when the average onerecler consisted of an intermittent chase over housetops and across mountains, the picture business had little appeal to those men of enterprise who like to call themselves substantial. Manufacturing of films in that "wildcat" period centered in Europe. The selling of the new form of entertainment to the ultimate consumer in this country was done in stuffy nickelodeons, which pioneer fans entered with five-cent pieces and left with headaches. Every school child old enough to reach the eighth grade can remember when trick films were still in vogue.

The improvement which has come with such prodigious speed is not reflected simply in the elegance of new picture theatres, in the elaborate care used in the production field, or in the development of the industry as a business venture. The really significant alteration is in the attitude of the people towards the movies. The child of to-day looks upon pictures as regular plays, and upon the spoken drama as something bizarre and novel.

The underlying asset of the picture industry is. neither brick and mortar theatres, not studios, nor prints, nor good will, nor any of the other items that commonly appear on the balance sheets of the motion picture companies. That which gives value to the enterprise is the acquired appetite of the people for pictures. Those companies succeed most completely which best satisfy this new craving.

This hunger to see shadowy figures on the screen perform in the realm of romance and of sombre reality has become a moving force in the national life, the full implications of which are not yet thoroughly understood.

One-tenth of us, the people of the United States, flow into the picture theatres every day in the year, with the regularity of the tides. In other words, according to the estimates of the producers, each of us goes to the movies once every ten days. And whereas a nickel used to be a passport to the movies, it now scarcely does more than take care of the Federal tax.

Capital in the Movies

THIS passion of Americans to see drama projected on a screen is piling up wealth for those who have capitalized it. Press agents have had a few words to say about the wages of stars, and, even if one does not habitually believe press agents, the actual amount paid is still handsome. And the average director—not the handful of the very best—draws between $500 and $1,500 a week, to help him win bread, clothes, and shelter. Then, there are the magnates, the old type and the new, who, according to the news on the Rialto, are being well compensated for assuming risks, financing imagination, and growing as fast as the industry they are leading. Two hundred and fifty thousand men and women are engaged in the various stages of manufacturing, jobbing, and retailing plays for the screen.

Capital, frequently reputed to be timid, has nevertheless a real proclivity for streaming into the rivers where profits flow. Investable money, the stuff which has helped to build transcontinental railroads, skyscrapers, and great factories, lacks constancy. It makes intimate attachments which continue for many years, but it will stay voluntarily only as long as it is rewarded with income. New capital does not follow old, if the latter is being starved. From the Civil War until a few years ago, railroad and public utility securities were deemed gilt edged. They were the standard by which others were judged.

But in recent years, neither the railroads nor the public utilities, broadly speaking, have fared so well. Capital therefore has been seeking other outlets. This is reflected in the security markets, where new fashions now prevail. Motion picture, safety razor, perfume, and oil stocks have been absorbing capital that otherwise might have gone into the old type of investments.

Speculation in the Movies

IN the last six years, certain elements in money row have dabbled in the movies. Speculators who match their hopes against reality in the New York Curb Market became financially acquainted with the movies through stocks of the World Film and Triangle Film, whose fortunes have been fluctuating downward.

(Continued on page 126)

(Continued from page 124)

History repeated itself in the financing of some of the lesser companies. The same things that happened in bringing out stock of other industries were recapitulated. Countless smaller companies, which represented scarcely more than the fond fancies and ambitions of their founders, offered securities to whomsoever would buy. Female stenographers as a result took an impressive part in financing the fringe of the industry by buying such offerings. Many a five-dollar bill went into these stocks—and stayed there. Guardians of the public weal regularly get letters from disillusioned "investors" something like the following, which was recently written by a young working girl in Brooklyn: "In 1016, I purchased five shares of Moonbeam Motion Picture Stock at $5 a share. Can you give me any information about the above? Nite Brothers were the agents. I expect it is a lemon."

One of the evils of unregulated trading on the Curb is that companies whose securities are traded in are not compelled regularly to issue financial reports, indicating how they are flourishing. Companies whose stocks are listed on the New York Stock Exchange must issue regular statements. Falling into the ways that prevailed, several picture companies, whose stocks were offered to the public, kept their finances secret, although they were amply manned by energetic press agents. Under a reign of silence, rumors and "tips" are at a premium, and an intelligent estimate of values becomes extremely difficult.

Within recent months, men and firms who stand at the forefront in the financial community have been identifying themselves with the movies. Names like Kuhn, Loeb & Company, the du Fonts, G. W. Davison, president of the Central Union Trust Company, of New York, and E. V. R. Thayer, president of the Chase National Bank, of New York, have been sponsoring recem motion picture development, and movie financing has now reached a new plane.

The underwriting of new preferred stock of the Famous Players-Lasky Corporation, the stepping of several important personages of the financial world into the Goldwyn Pictures Corporation, and the flotation by financial men of standing of the stock of the new Loew, Inc., which has taken over the various enterprises of Marcus Loew— these three recent events are the main basis for the impression that Wall Street is now in the movies. The financial district has long had its "silent men", bankers who perpetually shunned the press, and now it has its silent drama men.

Is Wall Street in Control?

IN the milieu of independent film men, it is frequently asserted that Wall Street is now in control of the movies. To hear them dilate, one would think that the Morgans, Schiffs, and Stillmans were actually writing the scenarios, selecting the stars, personally directing the productions, and supervising the distribution. Those who view with alarm the influx of capital via Wall Street foresee many bogies. One of them is the phobia that Wall Street is seeking to dominate the screen for propaganda purposes. However, unless one secs red constitutionally, one is unlikely to find any evidence that the Wall Street interest in the movies originates simply from a realization of its uses for propaganda purposes. (Incidentally, there are about ten major producing companies, and enough independent, smallet enterprises, financed mainly through private sources and Pacific Coast banks to bring the total to about 125.)

Men of finance have apparently gone into the movies primarily because of the prospects for profit. The old leaden of the industry have wandered intc Wall Street because the movies had outgrown the old financial methods of getting capital informally through private channels. The industry had advanced so far that it had become feasible and in the opinion of the captains of the trade, worth while to summon the special ability of Wall Street to attract the savings of men and women all over the country to motion picture securities As a rule, the financial institutions do not hold the securities they underwrite themselves, but merely market them throughout the land.

Besides capital, the financial men are contributing system and business method, elements which the motion picture industry conspicuously lacked. Expenditures in the companies affected are being budgeted more scientifically, and the salaries paid to executives are being carefully scrutinized. At the moment, the free and easy ways under which the movies have sprung to greatness since their birth about 1894 are clashing with the passion for card indexes and efficient accounting of Wall Street and big business.

A Movie Census

AN official census has never been taken of the cinema in America, but one is now definitely promised. Facts about the industry are therefore still a good deal diluted with guesswork. However, it is estimated that there are 15,000 picture theatres in the United States, with a sealing capacity of more than 8,000,000. and about 1,200 theatres under construction. In all the rest of the world, there are no more than 17,000 temples of the cinema. In 1919, which was a year of unprecedented prosperity in the industry, it was estimated that the net earnings of the theatres represented 15 per cent of gross receipts and 25 per cent of the capital invested. In 1018, $250,000,000 was invested in all branches of the industry, but the sum has since mounted with a startling rapidity. In the past, the growth of the industry has been financed mainly out of its own earnings by pyramiding profits.

As the motion picture industry stands to-day, Adolph Zukor, president of the Famous Players-Lasky Corporation, recently told his stockholders, "it is the most convenient, the cheapest and the most popular form of amusement. I believe the industry will continue the rapid growth which it has lately been experiencing."

Since the movies plunged into high finance, there has been much sentiment in favor of stabilizing the industry, because investors want a regular and certain income.

Captains of the industry contend that it has emerged from the period of excessive risks, particularly in the retail phase. They call attention proudly to the extremely few foreclosures of theatres. And yet the production of a picture involves great hazards, just as paying to see one does. The author of the scenario may be eminent, the star may be gifted, and the director talented, and still after the elements are well mixed into a five-reel picture, the product may be wretched. It may be a failure artistically or financially. But then it should be remembered that even the incomparable Shakespeare wrote an occasional poor play. Even Shaw himself is occasionally dull.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now