Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Artist Enters the Close-up

A Discussion of the Development of the Movies Toward Artistic Lighting and Setting

KENNETH MACGOWAN

IT takes no particular optimism to believe that the art of the screen has not reached the peaks in Theda Bara, Tom Mix and Mack Sen nett. Or, for the matter of that, in D. W. Griffith and George Loane I ucker.

The movies know it, if the critics don't. This "industry" which has rushed in ten years from "two-reel Westerns" to Broken Blossoms, manufacturing a whole new technique of acting, stage direction, photography and story telling on the way, finds it devilish hard to stop moving. It has an instinctive genius for recognizing the limitations of what it has done, and for seeking new roads to accomplishment. It may brag—and justly—about its Miracle Man and its Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, but subconsciously it discounts all it has accomplished, and goes on seeking some new creative factor to redress the balance of the old.

That is the meaning of this year's phenomenon, the entrance of the artist into the movies. I am inclined to doubt whether the Zukors, Laskys and Hearsts know precisely what they are doing when they hire Paul Chalfin, the decorator, Penrhyn Stanlaws, the illustrator, and Joseph Urban, the scenic designer. They may imagine that they are buying better backgrounds for Gloria Swanson, Bebe Daniels, "the good little bad girl", and Marion Davies; but the instinct which makes them know that all is not well in movie-land, has led them to a step that must end in the supplanting of that second-rate mechanician called the director by a supervising artist who sees human drama in pictorial form. Whatever Mr. Stanlaws' abilities may be, the intention in his case is to graduate out of interior decoration into direction. Pointing the way more decidedly, Norman-Bel Geddes, the young designer of opera and stage settings, is uniting with Rob Wagner, the prose laureate of Hollywood, in a project for the joint production of a new type of motion picture.

(Continued on page 110)

(Continued from page 79)

The Early Development of the Movies

SUPERFICIALLY, here is the logic of the movie magnates. They have tried various methods of production and emphasized various factors in the process. First there was the day of the company, the day when the public went to see a "Biograph" or an "NYMP," rather than the work of D. W. Griffith and Mary Pickford or Thomas H. Ince and W. S. Hart. With the break-up of the old-line companies came the ascendancy of the star. The discovery by the public, as well as the producers, that the presence of some particular set of curls did not necessarily insure a welltold story, resulted in a tendency to exploit the director. Even with star and director accounted for, there seemed to be a weak spot in the motion picture armour; somebody noticed that the scenario writers were usually long on technique and short on human material. The result was the starring of popular writers like Rex Beach, Rupert Hughes and Mary Roberts Rinehart. The fact that these diverse factors—star, director and author—usually fail to fuse, has led one or two perspicacious persons to the notion that moving pictures might be more picturesque and more moving if someone who understood human emotions from the pictorial angle assumed some sort of supervision over the whole process.

Roughly, this means bringing to the screen a considerable part of the revolutionary ideas and revolutionary methods which Gordon Craig and Adolph Appia have at last thrust down the theatre's throat. It means pushing these theories a little farther than they have gone even in Reinhardt's Deutsches Theater and Stanislawski's Moscow Art Theater. It means putting the artist completely in control of the whole process of production.

Like any healthy art in the first surge of life, the moving picture has travelled unconsciously much farther toward its necessary goal than many observers of its brief career would suspect. On the purely decorative side, the American screen antedated the American theatre in accepting and using large parts of Craig's philosophy. The Belasco tradition of rich detail had come to the screen through the Lasky Company's employment of Mr. Belasco's assistant, Wilfred Buckland, as art director; but the discovery of "Lasky lighting"—a flood of illumination from one direction —soon subordinated mere detail to a general warmth and richness of effect, centering about the actors. Robert Brunton, art director for Thomas H. Ince, took the next and perhaps most important step when he began to concentrate his lighting upon the actors in the drama by blotting out the greater part of his very solid settings in what seemed natural shadows. This made for a certain vivid dramatic quality in the light, and drew attention where it belonged, upon the actor.

Flashes of Pictorial Power

WHEN the Goldwyn forces, then uniting Arthur Hopkins and Edgar Selwyn with old-line motion picture men, first brought the painter upon the screen, it accomplished two new things. In Polly of the Circus, the film that Everett Shinn worked upon, night scenes were actually taken at night for the first time, and successful and artistic artificial exteriors were produced. In Baby Mine Hugo Ballin, the mural decorator, began to introduce simplified settings. He eliminated useless detail. He used large spaces of clear wall with restrained detail. In the decoration he began to suggest more of the habits and nature of the characters of the story than had at that time been attempted on the stage. Now, as the head of his own company, he is ready for more daring experiments.

Since Ballin brought simplification and suggestion into the movies—now almost three years ago—many attempts, both casual and deliberate, have been made at pictorial reform. Thus, under Maurice Tourneur, Ben Carré has tried, not very happily, to wed an artificial, poster-like sort of scenery to plays like Prunella and The Blue Bird. Just as Baron de Meyer adapted to photographic portraiture the "back lighting" of the screen, D. W. Griffith has utilized the soft focus of art photography in The Greatest Thing in the World and Broken Blossoms to beautify and heighten the emotion of the close-up. Through all the work of the best directors of the past three years run vagrant flashes of a pictorial power, which, whether deliberate or accidental, have heightened the dramatic effectiveness of scene after scene. I recall the simple and shining visions of Joan of Arc in Paul Powell's Susan Rocks the Boat; Allan Dwan's first scenes in Panthea, full of the true spirit of music; George Loane Tucker's two moving yet discreet expressions of youthful passion in The Hypocrites and The Manxman; the bare cathedral piers in the coronation scene of the De Mille-Buckland Joan the Woman; Christy Cabanne's application of Degas to his dancer in Diane of the Follies; Irvin Willat's idyllic countryside in the opening of Civilization, and the many beautiful scenes which Marshall Neilan linked with the gripping contrast of Mary Pickford's poignant little slavey in Stella Maris. In each of these cases it was not mere physical beauty that the director achieved, but a beauty expressive of dramatic action.

Moving Picture Manners

NOW, of course, I have catalogued not a tenth of the notable bits that I have seen in the past three or four years, not a hundredth of the total good output, and not one ten-thousandth of the dull, ugly and inexpressive scenes that have raced across the silver sheet since The Birth of a Nation. All that the directors have done by sudden flashes of inspiration, and all that the art itself has accomplished in its evolution from "Lasky lighting" to Ballin's simpler settings is almost trivial beside the mass of ugliness and bad taste with which the ignorance of the bulk of the motion picture directors has filled the screen and killed their drama.

This ignorance runs all the way from an inability to guess the emotions of a Wall Street broker who finds his wife enamoured of a Greenwich Village artist, to the habits of his valet and the decorations of his Adam drawing-room. Whatever these new artists of the screen may accomplish when they at last replace the third-rate actors and brokendown stage managers who at present have the last word on the screen, their first business, and the thing by which they will prove their right to directorship, will be the making over of the laughable interiors, grotesque clothing, misplaced furniture, impossible lighting and boorish manners which now clog and divert the photoplay's stream of emotion.

The most ignorant of directors could quickly, easily and cheaply find men and women who could put these matters right— if it weren't that their ignorance prevents them from knowing their errors, as well as the sort of persons with enough experience of life to set them on the right track. An intelligent butler or two could put these movie valets into proper clothing, and stop their constant bowing to "the master." A sub-deb could get them safely through a house party, and any one of a thousand decorator's assistants could keep them from mixing what I have heard called "Louis Quince" furniture with a Louis Quatorze setting. As for humbler milieux and less fine-spun emotions—it does not seem impossible that among the players and cameramen about them these directors might find a man or two less blind than themselves to the ordinary things of life through which they have passed.

(Continued on page 112)

(Continued from page 110)

The Case of Joseph Urban

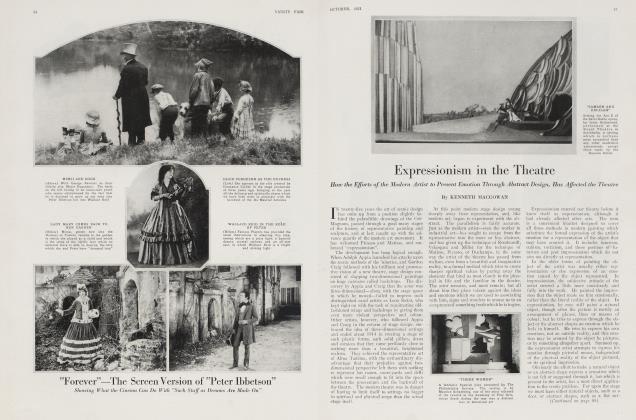

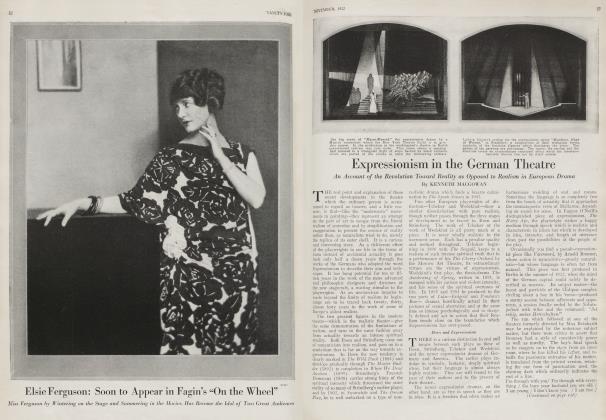

SO long, of course, as the present type of director continues his autocratic sway, the road of the artist—or the supervising butler—will be rocky, indeed. The case of Urban is demonstration enough. For almost a year, he has been working for the Hearst organization under what are probably the happiest circumstances that any artist is likely to encounter; yet the illustrations reproduced with this article should show the extraordinary difficulties under which any man labors who tries to give the average director either intelligent and beautiful lighting or an appropriate background.

In the two photographs of the artist's studio in The Restless Sex the impossibility of making a director light a room through its window (or, at any rate, to seem to do so) is characteristically shown. In the beautiful and elusive photograph in which the disconsolate artist sits bowed like his statue, Urban has arranged his lights to suit his own notions of charm and reality. The light of the scene appears to come from the window. In the other photograph the director has rearranged his lighting battery so that it streams down the walls above the window in a ludicrously impossible fashion. Another set of photographs shows a patio lit by Urban with variety, discretion and warmth, and relit blankly or with impossible shadows by the director. A still more interesting comparison lies between a dining-room designed and built by Urban and the room which the director insisted on having in its place. The story called for the apartment of a very sympathetic and imaginative millionaire, who had made his fortune in the lumber business. Since he showed himself a man of modern sympathies and ideas, Urban felt that he would turn the designing of his house over to an architect of modern tendencies, who would use as much wood as possible in the interior because he was building for a man who valued and loved wood. It was not a conception that appealed to the director. He scrapped the elaborate and beautiful set, and got one to suit his own ideas. From the ill-composed doorway to the "dining suite" of furniture, from the three negro caterers' assistants to the ostentatious lace tablecloth, the director has fitted perfectly the atmosphere of his production to the mood imposed upon his players.

(Continued on page 114)

(Continued, from page 112)

I have said nothing of the stories which the new artists of the screen will be expected to vivify, because while most of the fables of the films are almost unbelievable, plenty of good fiction has been screened—damnably. It will be their business to see that the motion picture lavishes its expensive and assiduous attentions upon interesting, plausible, human and screen-wise material. That should not be a difficult task, compared to ousting the directors who now make screen life hideous.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now