Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTag-Days For American Realists

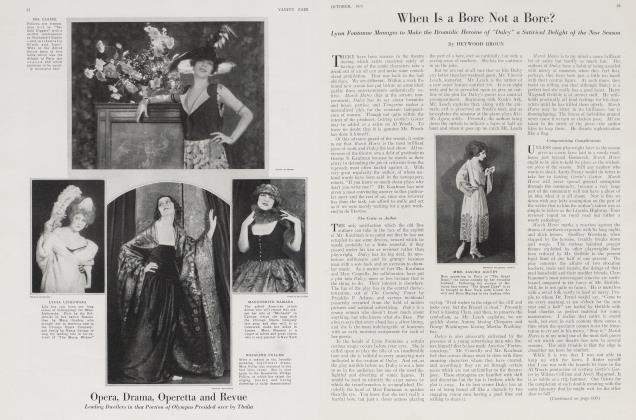

The Effort of the Novelist to Live Up to the Tag of the Critics May Well Prove Fatal

HENRY G. AIKMAN

Author of "Zell"

IN a highly complicated society and an age of specialization, the human intellect instinctively attempts to ease the strain of living by pigeon-holing fresh complications almost as rapidly as they arise. A jaded people like ourselves cannot possibly take the time, or undergo the mental fatigue necessary, for the real understanding of each new phenomenon that presents itself. Complete ignorance, on the other hand, is equally distasteful; it is a part of our vanity to feel we are "up on new things". We Americans, therefore—to a greater degree, perhaps, than the unfortunate foreigner—have found a characteristically ingenious solution: we escape the ordeal of patient mental labour, and simultaneously sop our national conceit, by the simple expedient of instantly cataloguing new things—of applying labels, more or less derisory, to novel manifestations we ought to know about and yet can't be bothered with looking into. To tag new people and new ideas saves a lot of bother, yet yields a grateful sense of quick perceptiveness. Mr. Edison is right: we will "resort to almost any expedient to avoid the real labour of thinking".

Jazzed News

OUR newspapers never exactly recondite, surely—sense our impatience with mere solid information. More and more they become "daily magazines", the apostles of sprightliness —witness the sporting page, with its jocular, "kidding" note and its expansion from one to three sheets. Pure news, like drugs in the modern drugstore, becomes rarer and rarer. Yet now, alas, even our newspapers bid fair to go under, as too intellectual, in the struggle with that marvel of mental economy, the "illustrated daily", which, hand in hand with the "educational weekly" film, gives us our news in pictures. Ten years more and our children will be educated without effort by moving pictures; and we, being so much more alert mentally than other peoples, being, in fact, so "quick and clever", we can grasp the most abstruse concepts instinctively, will do our jump to our conclusions without the necessity of reading at all—even now do we not begin to resent the one-line movie title?

Till that happier day, however, endure the fatigue of reading our newspapers we still must. But that fatigue, we have a right to insist, shall be minimized. We'll have our news "spiced up", or not at all. We want our sugar-coating. And when, to avoid the ignominy of appearing to be "back numbers", we are under the painful constraint of acquiring information about something new, something possibly abstract, we'll demand of our press, not accurate and illuminating presentation, but only the pseudo "short-cut", enough of a smattering of non-essentials to "get by" with. What's more, we want even that smattering "jazzed up"—the emphasis all upon the superficially striking, the unimportantly incidental, the sensationally personal. What we want, in brief, is a convenient tag, the idea in a nutshell—suggesting our easy familiarity and, wherever possible, our humorous contempt—for the instant subject.

Ask the Man on the Street about any one of the following concepts—old and new—and hear him answer—with that quick intuitive intelligence found nowhere save among Americans:

1. Evolution. (Extremely ancient, but still sure-fire.) "Why, that means we're all descended from monkeys".

2. Bolshevist. "One of those long-haired Russian birds who believe in free love".

3. Radium. "The stuff that shines in the dark".

4. Relativity. "Something to do with the stars, ain't it?"

5. Woodrow Wilson. "Ye-ah, I know— 'too proud to fight'."

6. Art. "Highbrow stuff".

One more—but in this instance, approach, if possible, one of the subject's kinswomen-by-marriage:

7. Realist. "Author of that disagreeable book? I do hope next time he'll write about something nice!"

Such labellings of his work, reaching the attention of the so-called "American Realist", must always evoke in him, I imagine, a degree of mild surprise. "Disagreeable?" Certainly he started out with no intention of being disagreeable, or even remotely shocking. In the beginning, he was, perhaps, conscious of two emotions within himself: first, a sense of annoyance with the feebleness, the false optimism, of most contemporary American fiction —this, and a very whole-hearted scorn for all sham; second, a certain feeling of his own about some phase of indigenous life—a feeling sincere, if somewhat saline—and strong enough in him to induce the impulse to transfer it, the impulse, in brief, to create Art. Your "Realist" thereupon set about writing his novel, as skilfully and—more to the point—with as little leakage of his first feeling—as in him lay. His "method", his "technique"—what, in fact, people call his "Realism"—was almost wholly unconscious and reflexive; it grew organically out of the precious substance (precious to him, anyway!) he sought to carry across into prose.

The Sudden Rise of the Realist

THUS our author toiled over his book and eventually brought it to completion. In the ordinary course of events, it would have sold its customary twelve hundred copies, and been promptly forgotten—just as its predecessors, the volumes of Messrs. Norris and Dreiser, had passed into magnificent oblivion. But now occurred a wholly unexpected phenomenon: several authors, instead of just one, had been seized more or less simultaneously with similar emotions and impulses. How this happened—why it came to pass at this particular time—no one has explained; to attribute it to post-war disillusion is not convincing: the result, at all odds, was the publication within a few months of each other of a fair-sized sheaf of respectable and competent American novels.

Now certainly nothing could be clearer—no matter what else may be said—than that here was no premeditation, no hint of imitation, no trace of a conspiracy among these authors to establish a new literary "movement" or cult. The novels themselves are so widely dissimilar —each is so distinctive and original—that their classification in one group seems incredible. Compare those first two, Miss Lulu Bett and Main Street; note how far apart they range in approach, in treatment, in viewpoint, in all their technical aspects, and even in their subject matter; their one common excellency, in fact, is the sincerity of the veridical impulse that produced them.

Yet the mere coincidence of numbers remained astonishing; the wonder of it began percolating through to the Man on the Street. Here, obviously, was something he should be "up on", however reluctantly. Thereupon the time-hallowed process of tagging the new phenomenon took place. The newspaper reviewers —assisted covertly by a few very shrewd publicity agents—presently evolved a facile, all-explaining catchword, a convenient handle. That catchword, that handle, was "Realism". The authors, much to their surprise, became "American Realists"—sometimes, quite regardless of birth records, the "Young American Realists". They had banded together to form a new "school" of fiction, it appeared. Another artists' fad. And by way of explanatory subtitle—for comic relief—we had the "Creed of Realism: Ugliness for Ugliness' Sake".

Everybody felt satisfyingly well-informed; the "Realists" reaped royalties on greatly stimulated sales; and the Man on the Street, comprehending the phenomenon with splendidly rapid derision, felt free to return to golf and the really worth while preoccupations of existence.

"American Realism"

A YEAR has passed; the fog begins to lift; perhaps by now it is possible to point out the simple fact that "Realism" is a misnomer in the case of five out of six of the current American novels to which it has been so loosely appended. The true Realism of the nineteenth century stressed literal fact, for example, without selection of either subject or detail; what passes for American Realism quite on the contrary endeavours painstakingly to select only such detail as is significant and highly relevant to the author's preconceived ideal. True Realism was a hard-and-fast philosophy of technique—I say was, advisedly, for it is long since dead; "American Realism" is a subjective viewpoint. One thinks of true Realism as tedious and verbose; its American cousin is nothing if not terse and very sharply etched.

The whole episode might be dismissed as an amusing Americanism, save that it has begotten two problems that now begin to vex our pseudo-Realist. One of his original impulses to creation, you will remember, was a very acrid annoyance at the namby-pamby in American fiction. His motivation, in part, was that of the revolté. Now revolt is admittedly a healthful and serviceable reagent, yet revolt become self-aware and self-approving inevitably becomes absurd and a bit insincere. Your "Realist's" first annoyance was capital; it drove him forth into fresh channels, it made of him an emigrant, a colonizer; it created new and vital forces in literature. But signs are not entirely wanting that our pseudo-naturalists begin to face the temptation of making a fetish of revolt for revolt's sake—even to capitalize their non-conformity—to write novels, in short, that are genuinely "disagreeable" and "ugly", without the justification of truth and the alleviation of sympathy. Your "Realist's" first problem, then, is to remain sane, even in revolt.

And his second dilemma arises similarly from the circumstance that he may have taken seriously all this pother about Realism. Granted, it does not much matter that the Man on the Street and his newspaper call you a Realist; the danger lies in the possibility that you will presently begin calling yourself a Realist. From that point on, the path leads straightway to self-consciousness, and thence to pose &nd empty, gaudy phrases. There is no more astonishing situation in all life—and none more grimly ironical—than the infestation of all Art by swarms of sciolists; here the atmosphere's very freedom seems to invite imposture. Thus for one actual novelist there are ten loquacious persons who will gratuitously tell him things about his book he never dreamed were in it. Nowhere else will you encounter such a clustering of dilettantes, so much confusion between the real and the spurious, so much ponderous talk about non-essentials.

Often the thing goes to ludicrous extremes. Note, for instance, the hot debate that constantly breaks forth afresh over the relative advantages of using a typewriter or pencil for the act of composition. Not long ago, a story of the writing methods of Mr. Booth Tarkington went the rounds. Mr. Tarkington, it appeared, wrote slowly, with infinite care; well and good, but more important—he always used a pencil. Not a pen, or a typewriter—a pencil. And not one pencil, but several. Not several ordinary pencils, either, but several sharp pencils. Mr. Tarkington was insistent on that score. He was the owner of a pencil-sharpening machine; each day, before commencing work, he would meticulously sharpen all his pencils—a dozen, perhaps; lay them carefully down on his desk; and—now mark attentively!—the instant he found the pencil in his hand becoming dull— ever so slightly dull—he would discard it in favour of one of the sharp pencils. Mr. Tarkington simply would not write with a blunted pencil; indeed, Mr. Tarkington's whole eminence as a novelist depended upon, nay, was inferentially the direct consequence of, the sharpness of his pencil-points.

At once, ninety-nine out of every hundred of the earnest young men and women who read this interesting information thrilled to the visualization of themselves employing henceforth only the sharpest of pencils; I myself reached the logical and pleasing conclusion that if I could achieve finer lead-points than Mr. Tarkington, I should assuredly be able to fabricate a correspondingly better product. The sales of pencil-sharpening devices increased inordinately; all over the country—in hall bedrooms, boudoirs, farm houses, even in kitchens—countless neophytes sat themselves down with portentous mien, resolved that thereafter success was to be impaled upon pencil-points very, very keen.

The Danger to the Artist

SMILE at such tragedy if you can. Every editor, every writer of newspaper "specials", knows how eagerly such personal idiosyncracies are devoured. What made Mr. Booth Tarkington turn to fiction—the obscure origin of his writing impulse; the story of his long and dreary apprenticeship; what his professional motives and convictions are: of all this—nothing. But of Mr. Tarkington's meaningless routine, his incidental habits of composition—if possible, of the look that comes into his eyes when he writes—columns.

Yet it is inversions only slightly less absurd and more subtle that menace the author who has begun to call himself a "Realist". The emphasis has already passed from the inner grace to the outward appearance. Presently you will hear him discoursing profoundly of his "method", his "style". Soon he will attempt to be the author some reviewer has said he is, to live up to the kind of work "confidently predicted" of him—to write not the thing that is in him and of him, but what he fancies people want and the critics expect. Thus all reform—at first the reflection of sincere and spiritual impulses—becomes in the end itself rigidly formal.

For both of the "American Realist's" problems, then, the solution lies in the refusal to think of himself as a Realist—or any other sort of "ist"; in remembering that so-called Realism—whatever else it may be—is not a "school", not a technique, but instead a distinctive reaction to life; in perceiving that his hope of artistic salvation can be realized only by seeing life whole—in three dimensions— not with any premeditated squint; and finally, having disregarded formulae and the catchwords of the Man on the Street, in transmuting his artist's emotion into prose as simple and as natural as he can contrive—most of all, as appropriate to his own particular vision.

On more practical grounds, as well, it might be prudent for him to disavow Realism. Evidences multiply that the Man on the Street and his newspaper grow tired of their yearling. A lady reviewer of Des Moines, Iowa, revolts:

"We are becoming a little weary of all this talk by and about 'the younger realists' (they and their admirers have so much to say!)"

A graceful note, perhaps, on which to close.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now