Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowNotes on Painting and Sculpture

Comments on the Current Exhibitions in New York

PEYTON BOSWELL

THERE is pathos and joy in the display of seventeen oil paintings and twenty-four water colours by Mary Rogers, at the Dudensing Galleries. The first emotion springs from the fact that only through her death did this artist centre the attention of the art world on herself. Her genius was recognized in her lifetime by certain fellow artists, among them Robert Henri, but she had no measure of popular appreciation. Yet she travelled further along the road of Modernism than almost any other American. And she was wholly American, her art being spontaneous and uninfluenced by anything in Europe. Yet she got in her paintings the beauty of structure that Cezanne attained after a lifetime of effort, and a spiritual and evanescent quality that Cezanne strived for and never obtained, as his admirers sorrowfully admit.

Mary Rogers died at the age of thirty-eight, after painting for twenty years. Triumph came too late for the painter, but in plenty of time for the glory of American art.

One of the most admired works is Through Trees, which reminds one a little of Cezanne's Landscape in Provence, which was shown in the Metropolitan Museum's display of Modernist works. Another notable piece is Dancers, exquisite, delicate, full of music. Then there is Purple Hills and Spring, joyous and melodious, and The Boats—Cutchogue, a symphony in pale greens, blues and pinks.

GLEB DERUJINSKY, whose annual exhibition is being held at the Milch Galleries, is a Muscovite artist who has duplicated in sculpture the success in America that the dancers of Russia had previously made in another branch of art. His popularity is due to the same qualities—spirit and abandon. As a portraitist he displays daring vitality.

The most striking thing in the exhibition is a carved wood group, a Leda and the Swan. If that good wife Juno could have seen Derujinsky's interpretation of this incident, and known that the swan was none other than her adventurous spouse Jupiter, there would have been crockery flying on Olympus or perhaps a celestial divorce suit.

Achilles and Hector is on the catalogue for display on November 23 only, for on November 24 it was to have been awarded as a trophy in the international fencing series. Icarus, who, equipped by his father with wings, flew too near the sun and got them melted, is likened by the sculptor to his native Russia, whose wings have been scorched by a red planet. Embarrassment is a characterization of a bashful young woman, the wildly dancing Odalisque has Margaret Severn for its model, and Columbine and Harlequin, Adolph Bohm and Ruth Page. For the rest there are busts, figures and statuettes, each with an individual appeal.

NOT so very long ago the art world was excited over an anonymous circular that protested against the PostImpressionist show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and which, in the most bitter terms, denounced modernist artists as insane and worse. It was the old, old stunt of conservative-extremism, heaping vituperation on what was new and strange.

It would be interesting to know what the writer of that attack thinks of the twenty drawings made by William Blake in 1823-27 for Dante's Inferno, which have been on view at the Scott & Fowles Galleries. Blake is now a classic. He is one of the "old masters". Even Joseph Pennell subscribes to his greatness. And yet, were he transplanted from the early nineteenth century to the early twentieth, he would be classified with the Post-Impressionists (or better, as the Germans put it, the "Expressionists").

As Martin Birnbaum says, Blake, when drawing, "would hesitate at nothing; to create a surprising design, or to intensify an emotion, real or imaginative, he would strain his figures, invent anatomical distortions, or violate nature in any way to attain his end".

The twenty drawings shown, which are a part of the original set of 102, are certainly distortionate but equally colossal as works of art. Think of it! Blake and Picasso and Matisse on the other side of the River Styx, dodging behind boulders to save themselves from a conservative mob bent on avenging "good drawings"!

THERE are two kinds of art—the art that critics write about and collectors crave and the art that everyday people use and enjoy in their everyday life. The former is of great consequence, but the latter is far the more important. Masterpieces give rare pleasure to a sensitive few, but the common art that adorns the walls of people's homes, makes furniture and cutlery more attractive, finds its way into newspapers and magazines as illustrations of advertising and text, is the thing that serves to make the aesthetic standard of a whole nation and its products.

"And its products" means a very great deal when analyzed. Somebody writing from Munich not long ago said the Germans were paying a great deal of attention to industrial art since the war, because they know that when value is added to a manufactured product because of its beauty, it means an increase in the economic wealth of the nation without the using up of any of the nation's raw* material.

Certain deep-thinking persons in this country have earned a genuine right to the title "art patrons" by promoting the Art Center, Inc., which has opened commodious galleries at Nos. 65-67 East Fifty-sixth Street, New York, to be used exclusively for the promotion of American industrial arts. The institution threw open its doors on November 1 with an exhibition that is tremendously significant. Three things will be achieved—the artist will be afforded an opportunity, to place his designs before the manufacturer, the public will be led to demand more and more beauty in the things it buys, and genius will be encouraged to think that there is nothing ignoble in creating artistic objects "for the trade". The Art Center, fulfilling this mission, marks an epoch in both the cultural and economic life of the nation. So far it has stirred the enthusiasm both of manufacturers and of artists, as is evidenced at the opening exhibition.

The broad scope of the Art Center will be understood from .the fact that the first display contains large exhibits by the Society of Illustrators, the American Institute of Graphic Arts, the New York Society of Craftsmen, the Art Directors' Club and the Pictorial Photographers of America, besides a section devoted, in exposition fashion, to manufacturing concerns that are taking the lead in putting beauty into American products.

(Continued on page 5)

OLD English sporting prints have long been a fad in America. Finer specimens have been eagerly sought by collectors, and even those that were merely picturesque have made desirable decorations for the country houses of the wealthy. American sporting prints have been almost negligible, but at last a beginning has been made, as is shown at the current exhibition at the BrownRobertson Gallery, where the water colours and prints of William J. Hays are being shown.

Mr. Hays has done the Millbrook Hunt under the title With Hounds in Dutchess County. Following the old English idea, the set contains four prints in colour, The Meet, The First Flight, Full Cry and Rtin to Earth. Being a fox hunting set, of course there is a superficial resemblance to the old English prints. Closer inspection reveals them to be American and of 1921.

The Meet has for its setting the little village of Mabbittsville, New York. The dogs are not English, nor the horses, and the natty habits, despite the red coats, are decidedly American. The Ford truck in the road puts in a finishing patriotic touch. Then, the rail fence in The First Flight, as well as the joyous and lightsome American colour, is distinguishing, and in Run to Earth the hillside with its sparse second growth of New York timber fixes the locality.

There is fine colour and lots of spirit in Mr. Hays' work. His beginning is full of promise.

THE dreams of a mystic, shadowy and vaguely blending in beau'iful colour, are expressed in the paintings and monotypes of Henry Wight, who is having his first exhibition at the Ehrich Galleries. His productions are unlike anything else in art, though perhaps they have a slight flavour of Redon and some of the colour music of Monticelli. They are original and aboriginal. The artist never "studied" art. He simply sat down and painted. He never had a model. His colour and form were drawn from his "inner consciousness". His work is "Expressionism" in its most literal sense.

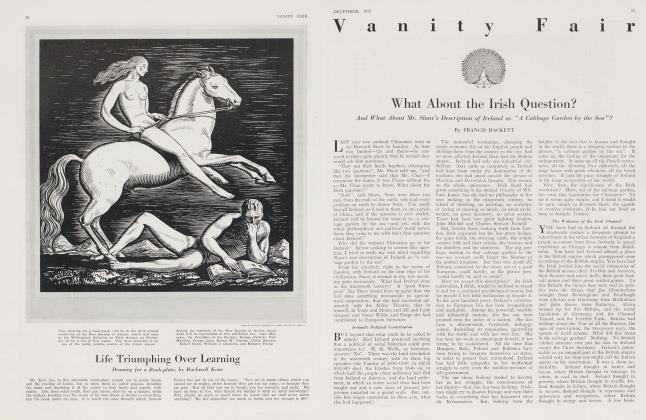

Creative Desire is a nebulous swirl of colour with figures; The Outrider of the Storm a plunging horse in a mantle of clouds, his flanks goaded by lightning; Submerged Life, a suggestion of the deep sea; The Flame of Passion, a whirl of angry red; Above the World, a symbolical mother leading a string of babies out of the unknown.

It would be pure speculation to predict how far Henry Wight will go. It depends upon what is inside of him; he will find expression for it, whatever it may be.

Word comes that Howard Leigh, America's youngest recognized etcher, is going back to medical school.

He started out to be a doctor before he undertook to be an artist; when he took up the burin he let fall the scalpel. But his rematriculation does not mean that Mr. Leigh is going to desert art, in which he has made a phenomenal success. At school his interest will be solely in anatomy. He wants to know what lies underneath the surface of the human body.

From this it can be inferred that Mr. Leigh has ambitions more ambitious than the architectural subjects which, last season, won him fame at a single exhibition. There was an inkling of what he aims at in his second annual exhibition, recently held at the Anderson Galleries. Study—Three Nudes is a delightful bit, and so is a dry point, The Fan, behind which peeps part of the countenance of Hilda Spong. This leads us to a delightful side issue, for— on his invitations—Mr. Leigh printed a little reproduction of The Fan and under it the following testimonial from Miss Spong: "All my life and all over the world I have been painted and photographed. I consider this my best portrait". Nothing below the bridge of Miss Spong's nose appears in the print, so one can see the magnitude of the etcher's achievement. It is very good, and one need not have any qualms if an irrepressible little laugh is aroused by the actress's "testimonial".

There were two superlative new lithographs in Mr. Leigh's show, both revealing different sides of the new Harkness Tower at Yale. The scaffolding had hardly been torn away before the artist was on the job with his pencil. His interpretation leads us to know that in the Harkness Tower the designer, James Gamble Rogers, has given America a piece of architecture of exceeding beauty and originality.

SIMULTANEOUSLY with Mr. Leigh's display was an exhibition at the Anderson Galleries of water colours over which many persons grew sentimental. Ever hear of anybody feeling emotion at a water colour show—that is, real emotion? Wait until you hear about this one, and, if you are more than forty years old, it'll get you, too.

The emotion had little to do with the pictures—they were just water colours. But the introduction to the catalogue told something about Walter Brooks Spong, who painted the water colours and brought them with him from Australia. He is the father of Hilda Spong, and a veteran scenic artist. He began to paint theatrical scenery back in the late 60's. He did the scenery for Trial by Jury, the first collaboration of Gilbert and Sullivan; for Miss Bateman's Leah the Forsaken; for Mary Anderson's Ingomar and for other famous productions by D'Oyley Carte, John Brough and Dion Boucicault.

The water colours were faithful and colourful reproductions of scenes all over the world, without the faintest trace of the influence of Van Gogh, Cezanne or Picasso. They included picturesque bits from England and Tasmania, the Azores and Ceylon, Egypt and Wales—from the brush of an old man who showed his first picture in 1867 and who worked with Gilbert and Sullivan!

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now