Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowNotes on Painting and Sculpture

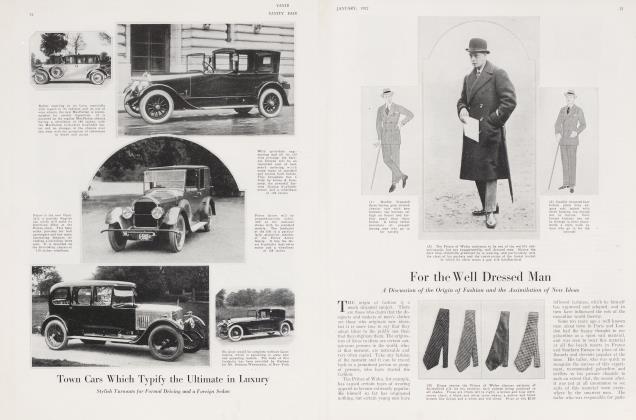

Comments on the Current Exhibitions in New York

PEYTON BOSWELL

IN discussing the Winter Exhibition of the National Academy of Design, Harry Watrous, for many years an officer of the Academy, and now vicepresident, said the reason no examples of Modernism found their way into the show was that no good specimens had been submitted to the jury of selection.

"I have no doubt," said Mr. Watrous, "that if the better exponents of PostImpressionism of the abstract in art should send their works to the Academy, the jury would accept them and they would be hung by the committee. We have heard too much of the narrowness and conservatism of the Academy. If the Modernists will send really worthwhile specimens to the annual exhibition next Spring, I honestly believe you will see them on the walls."

Mr. Watrous added that the few specimens of extremism submitted for the Winter Exhibition were so palpably worthless as "expressions" of anything that they were rejected.

There's going to be some fun. Certain of the Modernists, when told of what Mr. Watrous said, declared that in the last few years many worthy examples of their art had been submitted to the Academy, but that of late, discouraged by the attitude of the juries, they had ceased to try. They expressed a determination, however, to see to it that if no extreme art is seen at the Academy next Spring it will be the fault of the jury of selection.

Maybe it has come time for the National Academy to recognize that there is meaning and beauty in Post-Impressionism and in abstractions of form and colour. If this should happen, then Expressionism (to use the word so aptly coined in Germany) will become academic—at least in the literal sense of the word. The next step will be to admit such exemplars as John Marin, Samuel Halpert, Marsden Hartley and Charles Demuth to the Academy. Just think of it, John Marin, N.A.!

Suppose it should happen—suppose even that the worst should come to pass and that the National Academy and the public in swallowing a little of Expressionism should swallow it all. Suppose all the artists should begin painting abstractions and turn their backs on pictorial representation. Well, there would be a few years of it, then a group of revolutionists—outside the Academy, of course—would begin painting like E. L. Henry and Frans Hals and Childe Hassam, raise a fearful rumpus because of academic conservatism, and start the fight all over again.

This may sound like a joke—it's meant for one—but something of the sort makes up the whole history of art. Acceptance leads to satiety and satiety leads to revolution.

CERTAINLY pictorialism snade up the sum total of the Academy's newest display. It was no worse than in the past, but its mediocrity was more noticeable, not only to the eyes of jaundiced critics, but to the public as well, since so much of Modernism has begun to be displayed in the dealers' galleries. Within the last year Expressionist art has been seen at Montross', Daniels', Kingore's, Dudensing's, Brummer's, Weyhe's, De Zayas', Hanfstaengl's, the Société Anonyme and the Anderson Galleries; and rumour has it that the American Art Galleries some time in the New Year will disperse at auction an extremely important collection of Modernist art brought over from Europe.

Be this as it may, there is so far no sign of capitulation on the part of the National Academy. The prize-winning pictures are significant. The first Altman prize went to E. L. Blumenschein's Superstition, a realistic work of the socalled Taos school of the Southwest, with aboriginal motifs. The second Altman prize was awarded to The Sunrise, a muralesque work with figures calculated to give joy to Edwin H. Blashfield and Francis Jones. The Carnegie prize was won by Charles S. Chapman's Forest Primeval, which harks back to Courbet. The Shaw prize went to Dorothy Ochtman for a still life, The Tang Jar, which beautifully upholds the academic standard. High River, by John F. Folinsbee, won the J. Francis Murphy prize; The White Vase, by George Laurence Nelson, the Isidor medal, and Ernest F. Ipsen's portrait of John Lane the Proctor prize. All are excellent paintings—breaking no traditions.

THE third annual exhibition of the New Society of Artists at the Wildenstein Galleries, No. 647 Fifth Avenue, (November 15 to December 15) owed its brilliant success to Mrs. W. B. Force. Last year the exhibition was an artistic and pecuniary failure. The artists sent what seemed to be their worst pictures, and few visited the exhibition. This year Mrs. Force, in consenting to manage the show, compelled the artists to send their best works. And then she got the public to visit the exhibition by advertising in the newspapers and magazines and in the Fifth Avenue buses. The crowds came— sometimes in such number they could hardly see the pictures—and many works were sold.

Thirty-eight well-known painters and sculptors contributed 110 exhibits. These ran almost the whole gamut of American art. Even Modernism came in for a moiety of attention through the work of Samuel Halpert, Henry Lee McFee, Maurice Sterne and Gaston Lachaise.

Probably the most meritorious picture was Eugene Speicher's Southern Slav. Others that deserve special mention were Van Dearing Perrine's Autumn, Ernest Lawson's Windy Day, Jonas Lie's Sycamores in Storm, Hayley Lever's Wind, Leon Kroll's Spring, Rockwell Kent's November and Robert Henri's nude, Helen.

Unforgettable was one of Guy Pene du Bois' trenchant social satires, New York Girls. There will come a time when collectors will seek this artist's work as something unique and inimitable in American art.

WHEN Mrs. Albert Sterner announced she would hold an "Anonymous Exhibition" at her new gallery, No. 22 West Forty-ninth Street, the wise ones smiled and doubted if such a thing could be done except in name only. The sophisticated rounder of art exhibitions believes himself to be possessed of the ability to identify the work of a well-known artist at a block's distance. It was a curious experience to find themselves groping for clues at Mrs. Sterner's show (November 15 to December 15). Decision is not at all so easy of a picture when the signature is omitted. At sucha game an artist, with his knowledge of his colleagues' peculiarities of brush stroke and palette, has much the advantage of a layman.

Continued on page 9

Continued from page 8

There was a large nude which caused many to say "Robert Henri" at first glance. Closer inspection revealed certain bold strokes that led to a revision in favour of Randall Davey, in spite of the warm transparent glow of the flesh.

But in the background, through the window, was a tiny telltale glimpse of landscape that put both Henri and Davey out of the running, and, when labels were put on at the end of the first two weeks, sure enough the painter was none other than George Bellows.

Then there was a decorative subject in spectrum colours, a little girl seated at a table with lots of flowers, and the spectator said, "Renoir 1" Nothing of the sort! Glackens.

Of course, there were certain artists of such marked individuality and technique that no one could mistake their work—for example, a Holy Family with shepherds bearing gifts, in beautiful deep and dull colours, by Eugene Higgins, a winter landscape by Rockwell Kent, a harbor and boat scene by Jonas Lie, a deliciously humorous pseudoclassical landscape with figures by Bryson Burroughs, a tapestry-like group in a park by Maurice Prendergast, and an entrancingly coloured flower piece by Eugene Speicher.

It was Mrs. Sterner's idea to give collectors a chance to buy pictures on their own merit, regardless of name. The show was a success, because several works were sold in the first two weeks, one of them being a beautiful postimpressionistic Gloucester subject by Samuel Halpert, which should have been in the National Academy with a prize-label attached.

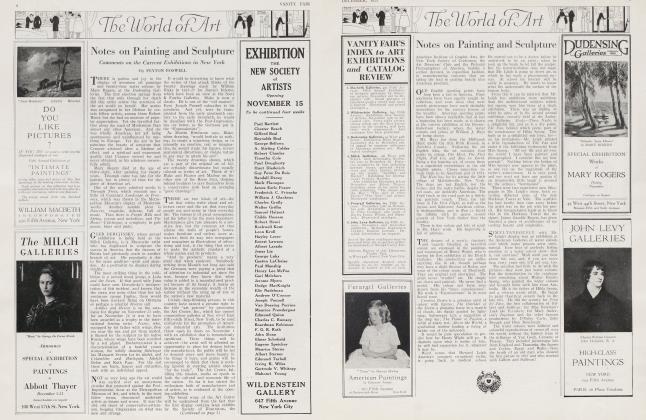

PIQUANCY, much vivacity and some extremity were found in the exhibition of work by Bernard Boutet de Monvel "and his friends" at the Dudensing Galleries, No. 45 West Fortyfourth Street (throughout December).

At least fifteen artists are represented in this very up-to-date show, including such confreres of Boutet de Monvel as Lepape, Drian, Marty and Choisnard. The animation of their graceful figures, their daring design and the telling effect of their colouring have been made familiar to the American public by the covers of Vanity Fair and Vogue.

NATALIE GONCHAROVA designed the first Cubist-Futurist stage set, the one which appeared in the Coq d'Or of Paris and London—not the one seen in New York. She and Mikhail Larionov, who have exhibited together in Paris and London, are coming to New York the first of the year and will hold a joint display of paintings and de-

signs for stage settings and costumes at the Kingore Galleries, No. 668 Fifth avenue (January 1 to 15). Larionoy will be remembered for his settings for the Contes Russes and the Soleil de Minuit.

These two artists lead the advance guard of Extremism in Russia, and conservatives in America may expect to be agreeably scandalized. There is an interesting rumour to the effect that a set by Natalie Goncharova will be seen in a play to be produced in New York early in the new year. Mary Hoyt Wiborg is chairman of the committee arranging the exhibition.

What a sudden jump from the decorative art of Christine Herter, full of academic and classic tradition, seen at the Kingore Galleries until December 17, and the conceptions of these two wild Russians! Being no less than the niece of Albert Herter, she has an undisputed right to the talents which have won so many laurels for the name in recent years. This display of her paintings includes portraits as well as pictures of purely decorative intent. One is a group of the Kneisel Quartet, painted for the Institute of Mulical Art.

THE first old master show of the season was that of Eighteenth Century English Portraits (until January), at the galleries of Arthur Tooth & Sons, No. 709 Fifth Avenue. The fourteen subjects in the show afford a study of English portraiture from Thomas Hudson (1701-79), contemporary of Hogarth and the man who taught Reynolds how to paint, down to James Northcote (1746-1831), one of the group that tried vainly to keep the tradition alive after the great masters of the English school had passed from the stage.

Reynolds himself is represented by a sketch of a boy, Master Henry Vansittart. The art of the supreme genius of the school, Raeburn, is exemplified by a large portrait of Lord President Dundas, who figured prominently in the impeachment of Warren Hastings—an ideal Raeburn subject, florid, stout, good-natured but with a stubborn glint in his eyes. There are two works by Gainsborough, a picturesque representation of his friend, Charles Frederick Abel, the musician, holding a great viol, and an earlier example, a robustious portrait of Philip Yorke, second Earl of Hardwick. There are two by Lawrence, a most pleasing John Hunter. Esq., eminent East India merchant, and a typical and spirited Miss Lennox.

An American note in the exhibition is as a Portrait of Miss Bainbridge, by Gilbert Stuart, a product of the artist's "Irish period". It is a most beautiful work, with refined grey and white pasfasages that give it the purity one often the finds in a Romney.

STUDIES by the late Abbott Thayer which have never before been exhibited are a feature of the collection of oils, watercolours and drawings provided by the artist's estate that form an exhibition at the Milch Galleries, No. 108 West Fifty-seventh Street (December 7 to January 1). Many of these drawings were preliminary works for pictures with which art lovers are familiar. Among them is the first conception of the boy's head that appears in Boy and Angel.

The post of honour is held by a large oil painting of A Muse, a semi-nude figure of grace and beauty, typical of the artist's best work. Among the

watercolours is one of Mt. Monadnock, which he often painted. It was on this mountain that he. desired his ashes might be scattered, after his death—a request carried out by his son.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now