Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

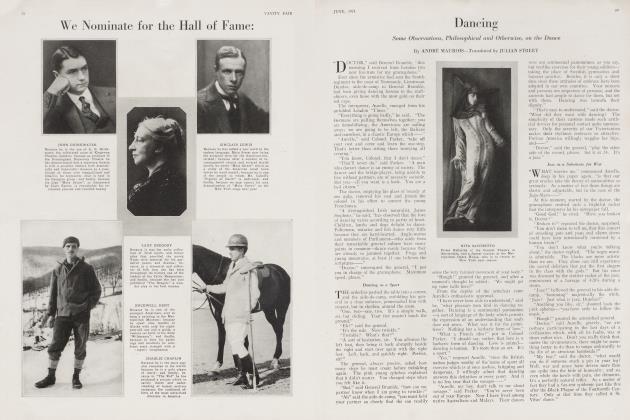

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowPortraits

An Account of the Reception of Beltara Among Those Strange People, the Scotch

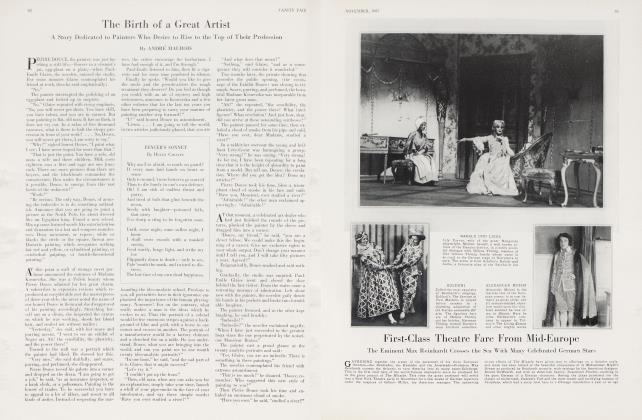

ANDRÉ MAUROIS

JULIAN STREET

THE French Mission, in its infinite wisdom, sent as liaison officer to the Scottish division a captain of dragoons, named Beltara.

"Are you a relative of Beltara the painter, Captain?" asked Aurelle, the interpreter.

"Beg pardon?" said the dragoon. "Repeat that please. You are mobilized if I am not mistaken? You are a soldier, at least for a while? And yet you claim to know that such things as painters exist? You actually admit the existence of that condemned species? You believe that there is in the world an art other than that of shooting off a gun. Ah, Interpreter dear, my duty is to have you locked up. But, alas! I am only a painter; so allow me —let me press your hand!" And he told about his visit, after he had been wounded, to the bureau of personnel of the Minister of War. An old colonel became friendly with him and tried to find him a job.

"What is your profession in civil life, Captain?" he demanded, his pen poised over a printed form.

"I am a painter, Colonel."

"Painter?" said the colonel. "Painter? Oh, Lord!" Then, after a moment of reflection, he added with a kindly, understanding wink: "Let's put 'nothing.' That would be better."

A Successful Friendship

CAPTAIN BELTARA and Aurelle, the interpreter, became inseparable. They had common tastes and different professions—the best recipe for friendship. Aurelle admired Beltara's sketches, showing the supple lines of the Flemish landscape, while Beltara was indulgent in his criticisms of the young man's limping verse.

"You would have talent," he told him, "if you weren't afflicted with a certain culture. An artist ought to be a cretin. Sculptors are the only perfect beings; then come landscape painters; then painters in general, then musicians, and then writers. And critics aren't exactly stupid, either. But of course men who are really intelligent do nothing."

"But Captain, why shouldn't intelligence be an art, as well as feeling?"

"No, my friend, no. Art is a game, intelligence is a profession. Ideas are as dangerous to art as a dynamo would be for a child's plaything. Take me, for instance—since I've stopped painting I actually catch myself thinking occasionally. It is very disturbing."

"You ought to do some portraits here, Captain. Doesn't the idea tempt you? Look around you at all this British flesh, so beautifully tinted by the sun and an inspired choice of drinks."

"Yes, yes, my dear fellow; it is a pretty subject, but I haven't the materials to work with. And besides, do you think they'd pose?"

"As many as you like, Captain. To-morrow morning I'll bring you little Dundas, General Bramble's aide-de-camp. He hasn't an earthly thing to do. He will be enchanted."

Next day Beltara made three crayon sketches of Lieutenant Dundas. The young aide-de-camp posed well enough, save for the fact that he insisted upon being allowed to shout like a fox-hunter, cracking his favorite whip and talking to his dog.

"Oh," cried Aurelle when the sitting was over, "what a splendid portrait! So few lines, yet it contains all England!" With the ritualistic gestures of the amateur of art, who caresses the fine points of a picture with a circular movement of the palm, he praised the naiveté and vacancy of the clear eyes, the charming flesh-tints, and the delightful candour of the smile.

Meanwhile, the pink young ephebus planted himself before his portrait, in the classic pose of a golf player, and striking an imaginary ball with an imaginary club, passed judgment on the work of art.

"My God!" he exclaimed. "What a frightful thing! Where the devil did you get the idea, old man, that my riding breeches laced up the side?"

"What does that matter?" said Aurelle, annoyed.

"Matter? My God! Would you like to be painted with your nose behind your ear? My God! That thing looks about as much like me as like Lloyd-George."

"The matter of resemblance is of minor importance," said Aurelle, contemptuously. "The thing that counts is not the individual, but the type—the synthesis of an entire race and an entire class. A good portrait has a literary quality. For instance, take the Spanish masters. The thing that makes them worth while is—"

"Years ago, when I was so poor I had to eat crazy cow in my native Midi," said the painter, "I used to do portraits of the wives of merchants for five louis apiece. When I had finished, the family assembled for an intimate view. 'Ho, yes,' the husband would say. 'Not so bad. But what about the likeness? You're going to put that in afterwards, are you?'

" 'The likeness?' I used to reply. 'My dear sir, I paint the ideal. I do not paint your wife as she is, but as she ought to be. You see your wife every day. Naturally she doesn't interest you. But my picture—oh, my beautiful picture! Why, you've never seen anything to compare with it!' Then the business man, outgeneraled, would go around to all the cafes of Cannebière, telling people: 'Beltara, you know, is the painter of the ideal. He didn't paint my wife as she is, but as she should be'."

"Well," interrupted young Lieutenant Dundas, "if you'd only make my breeches lace up in front I'd be tremendously obliged to you. I look like a damned idiot the way they are now."

The Stout Major and the Lean Colonel

IN the following week Beltara, who had procured some colors, made excellent studies in oil of Colonel Parker and Major Knight. The major, who was fat, found his embonpoint exaggerated.

"Yes," said the artist, "but when you get some varnish on it ..." He gestured appropriately with both hands, as though bringing the major's abdomen down to more modest dimensions.

The colonel, on the other hand, was thin, and wished to be filled out.

"Yes," said Beltara, "but when the varnish is on it ..." And his slowly separating hands promised most surprising expansions.

Becoming enthusiastic over his profession, he tried some of the best types of the division. His pictures had diverse fortunes, each model thinking his own portrait mediocre and the others excellent. The commander of the division squadron said his boots were badly polished; the chief of engineers severely criticized grave errors in the arrangement of his ribbons —the Legion of Honor of a foreign nation ought not to precede the Order of the Bath, and the Rising Sun of Japan ought to follow the Italian Valeur.

The only unreserved praise came from the sergeant-major who served as General Bramble's secretary. He was an old soldier, with innumerable chevrons, whose faunlike head was surmounted by three stiff, upstanding red hairs. He had the respectful familiarity of the subaltern who knows he is indispensable, and he came at all hours of the day to criticize the work of the French captain.

"That's fine, sir," he would say. "That's fine! "

After a while he asked Aurelle if the captain would consent to "take his picture." The request was well received, the living torch inspiring the painter to kindly caricature.

"Well, sir," said the sergeant-major, "I've seen many picture-takers like you, working at the Scottish fairs, but I've never seen a single one who could turn them out so fast."

He told General Bramble, over whom he exercised a respectful but powerful authority, about Captain Beltara's phenomenal speed, and convinced him that he ought to pose for the French liaison officer.

The General as an Artist's Model

THE general was an excellent subject. Beltara, who had the success of the portrait much at heart, asked several sittings of him. He arrived punctually, took the pose with admirable exactitude, and when the sitting was over, would say, "Thank you," with a smile and go away without another word.

"What about it?" said Beltara to Aurelle. "Does it bore him? Yes or no? He has never once stepped around to see what I was doing. It is unbelievable."

"He will look at it when you have finished," said Aurelle. "I assure you he is delighted, and he will tell you so when he sees the portrait."

After the last sitting, the painter having said: "I thank you, sir; if I try to do more I'll only spoil it," the general descended slowly from the platform, walked with solemn tread around the easel, and gazed at his portrait for a long time.

"Hough!" he said at last. Then he went out. Beltara made many portraits, but he was dissatisfied with all the men who sat for him. The painter-captain used to say to himself, "It would do me good to paint an intelligent sitter. They all want to look like a tailor's fashionplate. But I can't change my nature; I don't paint pomade; I paint what I see. It's the old story over again—the story of the art-lover Diderot tells us about—the man who gave a flower-painter an order to paint a lion. 'Certainly', said the artist. 'But rest assured of this—two drops of water couldn't resemble each other more than that lion is going to resemble a rose.' "

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now