Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Arrival of the Millennium

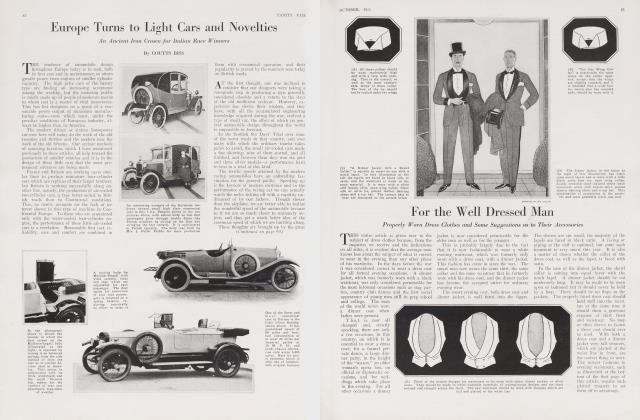

After Two Decades of Sombreness, American Cars Burst Forth in Brilliant Colours

GEORGE W. SUTTON, Jr.

IT was only six months ago that we were bemoaning in these pages the fact that the designers of American cars had always seemed to take their inspiration for colour schemes from the Melancholy Dane. Black was the order of the day and had been since that time, twenty-nine years ago, when a certain horse in Kokomo, Indiana, jumped through a barber-shop window at the sight of the first American automobile. By "black" we mean not only the actual funereal shade itself, but all those dark greens, blues, maroons and browns which, at a distance, are indistinguishable from one another and from the prevailing shades of night as well.

Various expert authorities on motor car styles concurred in our belief that there was too little originality in the appearance of the average car and told the automobile industry so in rather emphatic language. One highly placed student of automotive affairs went so far as to say that there was so much sameness in the appearance of our cars that it was becoming an ordinary experience for the man who had just purchased a new machine to have a neighbour stick his head over the fence, and say, "Well, Horace, I see you've got the old bus washed up again."

That was eight months ago. Today the American motor world is rapidly taking on the appearance of a blooming garden, or a New England boiled dinner; depending upon the observers' preference for bright colours or no colours at all. This time next year should see a great variety of bright colours on a majority of American cars.

By artists, black is considered the absence of all colours, just as white is supposed to be the presence of all colours. Therefore, American motor cars, in that they have practically all been garbed in black or near black, may be said to have had no colour schemes whatever. This might lead to the psychological conclusion that the motoring public, which has dictated colourless automobiles, is made up of colourless people, quite lacking in originality and mental variety. This is hardly so, however, because other factors, those of manufacturing convenience and the fear of deviation from the conventional, for instance, have entered into it.

Not so many months ago the managers of Barnum and Bailey's circus conceived a spectacular publicity stunt to accompany the aerial acts of Miss Bird Millman, who had been borrowed from Ziegfeld's Midnight Frolic. The stunt consisted in having Miss Millman enter the darkened arena in a pure white Essex touring car. You will not have to stand more than fifteen or twenty minutes on Fifth Avenue now in order to see a white car pass or draw up at the curb. Such a machine will attract but little attention in any numerous group of high class standard and custom built cars, because a majority of them, if they have been built since the first of the year, will very likely be done in various brilliant shades of light cream, oyster white, blue, purple, olive green, fiery red and other bright colours which, a year ago, would have been a certain indication of a degree of culture only half a generation old.

Bright colours, although less durable than dark shades, are practical and, if applied with knowledge and taste, are pleasing to the eye. You do not buy a vivid suit of clothes for fear you will grow tired of the pattern before the suit has been worn more than a few times. This need not, however, apply to those motor cars which have exterior colour schemes originated and applied by someone who knows his business. Light colours do not show dust and mud as readily as darker shades. Therefore, they do not require as frequent washing.

The selection of a colour scheme depends, to a certain extent, upon the manner in which a car is to be used. For instance, if you have a new car painted light grey and store it for the winter in a very dark garage, you will find in the spring that the paint has taken on a yellowish tinge. This has nothing to do with the paint but is entirely due to the change that takes place in the varnish which has been applied over the last coat to protect the finish. A number of other colours are also subject to this kind of deterioration.

Blue is one of the most popular motor car colours at the present moment. Probably twenty-five per cent of all new cars in the country are painted in some tone of blue, the most popular shades being turquoise, Joffre, peacock and electric blue. But this colour has its own drawbacks because it is subject to fading when exposed to strong sunlight for lengthy periods. The chemical composition of blue pigment renders it less able to hold its colour under the action of sun rays and its ingredients have a quicker effect than other colours in making varnish hard and brittle. It is only through consultation with painting experts that the most pleasing and the most lasting colour scheme for a car can be chosen.

Almost every one remembers the first man he saw wearing a wrist watch. It was an epochal event. It was in 1913, I think, that a mincing little male specimen wafted into the office with a timepiece on his wrist and a handkerchief up his sleeve. The effect was electrical. God had not been good to him in the matters of physique and personality and the watch and handkerchief represented his rebellious attempt at self-expression. It was only three years later, during the Mexican mess, that the toughest, hardest-boiled regiment in all the New York National Guard held a set of athletic games. The prizes were subscribed for by every man in the regiment and they consisted of—wrist watches.

(Continued on page 92)

(Continued from page 81)

Thus it is with automobile colour schemes and equipment. A year ago the motorist who decorated his car with a pair of windshield wings was a dude, attempting to outdo his neighbour in garish display. Today no sport car is complete without these very practical and ornamental accessories. Same for aluminum steps, spotlights, rear warning signals, front and rear buffers, luggage trunks, sun visors and other modern touches.

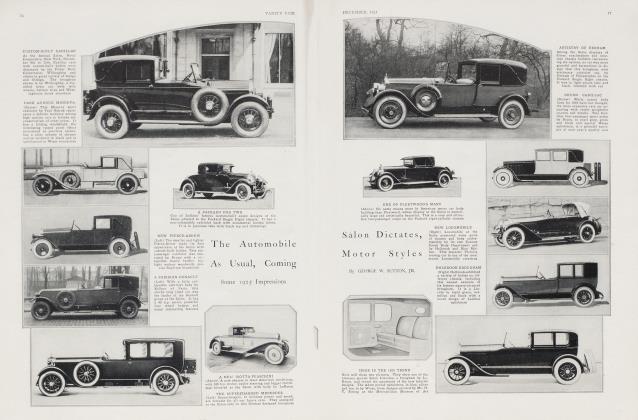

The motor car industry is in an interesting situation just now and a lot of things are scheduled to happen between now and Show time. At the moment we are in the throes of a price-cutting wave which is altogether artificial. The Cyclopses of the motor industry are girding themselves for a battle royal and a parade of new models of all kinds will take place leading up to the Annual Automobile Salon at the Hotel Commodore, New York, December 3rd to 9th, and in Chicago the last week in January; the National Automobile Shows at New York, January 6th to 13th, and in Chicago the last week in. January, and the Second Annual National Body Builders' Show at the 12th Regiment Armory, New York, January 8th to 13th.

It was in Europe, I think, that the first criticism arose that "American cars all look alike." Over there they have no such trouble because for various reasons, they have not yet solved the problems of mass production and each manufacturer builds cars of distinctive types which differ materially, both in appearance and mechanical features, from the machines of any other maker. There is the widest latitude in colour schemes.

We are likely to see wholesale evidence of this in the near future. The head of a New York agency for a foreign car is now in Europe and when he returns he intends to bring with him agency contracts for somewhere between ten and twenty makes of machines which have never been represented in this country. I do not know just when these cars are scheduled to appear here, but when they do you may count upon it that they will present a great variety in colours and considerable novelty in the matter of mechanical arrangement and body lines. A few of the European cars are doing very well in the American market. Others are making bad weather of it.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now