Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowA Stage Career for Girls

Some of the Stumbling Blocks in the Path of Her Progress

JAMES L. FORD

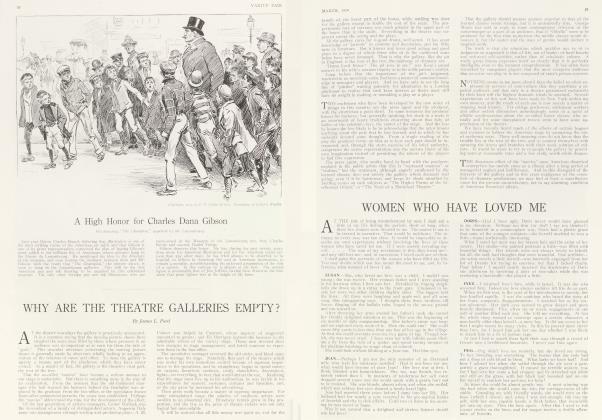

WE hear very much just now about the rapid advancement of women in the various arts and professions, but not so much, save in hysterical fiction, about the many things that impede their progress. And, as there is no calling that has a stronger or a wider appeal for young women of the best class than the stage, so there is none that presents more difficulties to the tyro. The girl who wishes to write or paint may be quite sure of receiving good instruction at the hands of competent teachers and the generous encouragement of the more advanced members of her chosen profession. But let a young college girl announce her intention of becoming an actress and she will encounter determined and stupid opposition on every hand.

Her family will laugh at her for being "stage struck" and, in an incredibly short time friends and relatives will emerge from the woods in which they have lain hidden for years to utter words of solemn warning. And the less these counsellors know about the theatrical profession the more impressive will be their utterances. They will assume from the start that she is headed for moral destruction, for are they not all primed with those novels of stage life which prove that the primose path is the only one that leads to success? Not one of them realizes that the same path leads also from the milliner's shop and the broker's office and that the ranks of the fallen are not recruited solely from the stage.

The Art of Repose

THE next hurdle that confronts the young tyro who has succeeded in passing over ridicule and bad advice is the dramatic academy, unless of course, she should succeed in getting into one of the few really good ones that honestly teach the art of acting. But, the chances are that she will fall into the hands of some unprincipled fakir who will teach her that acting is making a noise with the mouth and that a pair of leathern lungs are more to be desired than graceful carriage, a highly trained voice, or a mastery of the art of repose.

I asked one of these so-called "Professors" once if a certain one of his pupils whom I named had any real talent and his artless reply sent a flood of light on his business methods: "A very talented girl indeed! She sold thirty-eight tickets for our annual performance."

Fortunately not even such instruction as this can wholly quench the spark of true genius and sooner or later she who has a genuine aptitude for the stage will cease to sell seats for the annual public performance in which the Professor will appear in the chief part with the most successful ticket vendors in the minor roles, and the others huddled about him as wedding guests or happy peasants! Then she will begin her weary round of managerial and agent's offices, handicapped by the bad advice of her relatives and the erroneous ideas she has gained during her period of study.

What she had to endure while seeking her first engagement has supplied so many novelists with a theme and is, withal, so painful to think of or write about that we can afford to pass it over in silence, though I may remark that it usually takes a dramatic academy graduate about six months to come down from Nora in The Doll's House to "walking in." But her first engagement, no matter how pitifully small the part, is a matter of supreme portance to her because it lifts her at once from the ranks of the amateurs to those of the profession and she need no longer confess to a manager that she has never "been on" in her life. She can now reply to his inquiry "I've just closed with Only a Perfect Lady—you'll probably remember me if you saw the piece—I would rather sign with a better company. Too many hick towns with that sort of a show. If they'd shown me their route I could have taken something else"

Always Remember You're a Lady

IF I ever start a dramatic academy I shall train pupils to utter such lines as those quoted above with the firm assurance that seldom fails to convince.

It is with the words "Always remember that you're a lady!" ringing in her ears, and with a heart swelling with pride and ambition that the tyro passes through the stage door to her first rehearsal and finds herself in a group which is not altogether composed of ladies and is dominated by a professional producer who is quite as likely as her late instructor to give wrong instruction. If our young friend can begin her career by forgetting that she is a lady and treating her associates as if they were at least her own equal in social status she will have taken a noteworthy step in her advancement. Remembering that you are lady may be advantageous if you were cast to play Marie Antoinette but not if you were to play a scrubwoman or Zaza. Moreover if she looks down on her associates she will soon find herself looking down on her audience and this policy will render her unpopular in both groups.

Philosophers have often wondered why our most successful actresses are recruited from either the humbler ranks of society or from theatrical families, while of the many girls of education and refinement who enter the profession very few attain eminence. In my opinion 'remembering that you're a lady' is largely responsible for this condition. The inheritor of stage traditions is also the inheritor of stage instincts and has received instruction at the hands of experienced parents, while the girl of humbler beginnings respects an audience which she believes superior to herself and regards the leading members of the company with a veneration that shows itself in the scenes she plays with them. Thus she becomes without knowing it a "feeder" and by close attention to the lines addressed to her adds materially to the interest of the scene. In so doing she wins the favor of players of a higher degree so that they are anxious to have her in any company they appear in. This will never happen if she goes on the stage every night "remembering that she is a lady."

Of all the idiocies uttered regarding the stage none is equal to the oftrepeated "It takes a gentleman to play a gentleman and it takes a lady to play a lady." It takes an actor to play a gentleman and an actress to play a lady. Nor does it take a blacksmith to play a blacksmith, nor a victim of tuberculosis to play Camille. One of the most distinguished impersonators of aristocratic roles who trod the boards in recent years was Miss Ada Rehan, the daughter of a ship carpenter who worked at the Navy Yard beside Edward Harrigan's father.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now