Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowFrom Maupassant to Mencken

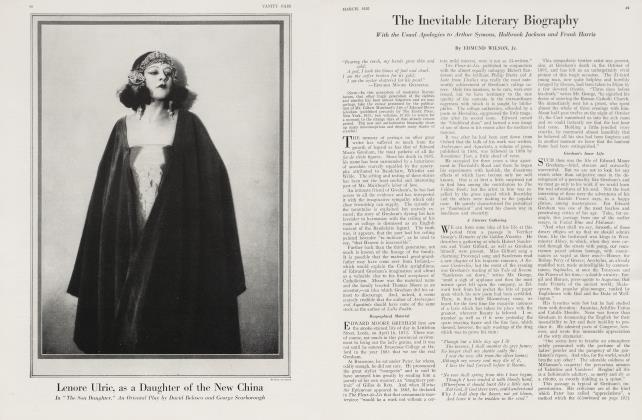

EDMUND WILSON, JR.

THE autumn has brought new books by both the two chief American satirists—Sinclair Lewis and H. L. Mencken. Both works are potent bombs in the great cause of blowing up 100% Americanism and both contain in a small quantity certain elements which should probably not perish with the downfall of the building to be destroyed.

Sinclair Lewis, in his novel Babbitt (Harcourt), has written a sort of satiric encyclopaedia of the American business man and the world which he creates, It is a compendium of all the charlatanry and bunk in which American life is submerged—the work of a man with a virulent passion for hunting down the vulgar and the silly. In fact, the attempt to make the satire exhaustive almost swamps the book as a novel. It is incredible that any actual human family could ever swallow so many sickening things as the Babbitts. I cannot, for example, quite believe that any genuine boy in his teens would ever devour the Power and Prosperity ads with the eagerness of Teddy Babbitt. This is to assume that people actually exist like the people in the advertisements—the people who are always represented as joyfully buying the products advertized. I have never seen any people like this and I do not believe there are any. The romantic race depicted in the backs of magazines and on the colored cards in the subway do undoubtedly correspond to some debauchable element in the American mind but I never knew anyone in my life who was completely made up of this element—who had nothing but the bumpkin imagination which is seduced by advertisements and boosting campaigns.

True, the whole point of Mr. Lewis's story is that there were other elements in Babbitt, which were crucified by the real estate business and the Zenith Athletic Club, but Babbitt, before he begins to doubt, is not a human being but an ogre and when, after his brief rebellion, he surrenders, he straightway becomes an ogre again—until the saving and rather fine scene on the last page.

Not, however, that it may not be something to have invented a good ogre, Dickens is full of ogres and Lewis has something the same sort of genius as Dickens. He is a master of taking the unamiable aspects of humanity and externalizing them as goblins and demons, But the trouble is that, unlike Dickens, his gift is almost entirely for making people nasty. In Dickens, there are not only monsters of malignancy but miracles of the amiably absurd—as well as heart-breaking angels of goodness. But Babbitt, like Main Street, is a book inhabited almost entirely by demons and by demons which have, after all, not quite the three-dimensional quality of Dickens's.

Yet, for all this, in the parts of the book where Babbitt does come alive, it becomes evident that Lewis has a strain of the genius which creates great ideal comic characters. There is a passage which seems to me almost the best thing in the book, in which Babbitt tries to amuse his brother's baby. "I think this baby's a bum," he says, poking his finger at it, "yes, sir, I think this little baby's a bum, he's a bum, yes, sir, he's a bum, that's what he is, he's a bum, this baby's a bum, he's nothing but an old bum, that's what he is—a bum!" In this single paragraph the whole soul of Babbitt is presented. As on comparatively few other pages of the book we see the sensitive human being in his essential gentleness and his touching spiritual impoverishment. Here Lewis approaches the inspiration of the really noble modem humorists —the Mark Twains, the Dickenses and the Frances.

But even when I thought it cheap or too shrill with an excessive rancor, I was enormously entertained by Babbitt. I seem to be almost the only living person who has never been bored by Mr. Lewis, but I found Main Street only a little too long and I have enjoyed every page of Babbitt.—In any case, his satire, like Mencken's, is the satire which is proper to the subject. You may protest that in assaulting the barbarians they behave like barbarians themselves, but the fencing skill of Voltaire or the barbed persiflage of Aristophanes would serve no purpose in America. When we have a more civilized public it may be that we shall have more graceful satirists. But in the meantime—since the enemy have clubs—let us not complain if the critics carry blackjacks,

Mr. Mencken as Poet

MR. Mencken does, however, in some ways though he makes even more noise than Mr. Lewis, have as a literary artist a somewhat finer quality. For one thing, he writes good English prose, which Mr. Lewis never does. For another, he has a kind of poetry and imaginative fire. It seems to me that it is upon these, rather than upon his critical ideas—good service as some of them have done—that his claim to distinction chiefly rests. The ideas expressed in his last book of Prejudices ('Knopf') seem to me in many cases extremely stupid. In one of his phases, Mencken is a sort of Babbitt himself—a credulous forward-looker who has somehow got to looking backward. He has the same simple faith in his pessimism that Babbitt had in his boosting. His conviction that Americans are unimprovable is held with the same dogmatic obstinacy and the same lurid eruptions of rhetoric as the conviction that they are the greatest race on earth by the speakers in the Chambers of Commerce,

But Mencken, for all the bluntness of his mind as an instrument for critical analysis, is a satiric creative artist of a very high order. In his portraits of Huneker and Dreiser, in his description of Munich in Europe After 8:15, in his magnificent rhapsody in The Nation about Harding's prose style (why has he not reprint^ it in this book?), even in a stray phrase like the one in a recent magazine article in which he spoke of dogs growling in their sleep over colossal bones, the muddy sediment subsides and the black fumes of hell-fire clear away. There is a genuine magic about the images which shine in the sun of his imagination. He has created something which is true to life and yet which is better than life— there is even a certain nobleness about it. This vein is to be found at its best in the last pages of this last book—particularly in the sketch called Virtue, in which the pitiful dreariness and vulgarity of the common American scene is fused into something more distinguished as art than anything to be found in Lewis,

(Continued on page 26)

(Continued from page 25)

Huneker's Letters

BUT in his new consideration of Huneker, Mencken becomes the evangelist again in a very singular way. Before he is done he is describing Huneker as if he were a reformer like himself. It reminds one of Bernard Shaw's perversion of the purpose of Wagner and Ibsen. Just as Shaw insisted upon binding the Ring to a socialistic interpretation and refusing to admit that Ibsen was anything but a radical pamphleteer, so Mencken will have it that Huneker was a great warrior against American Philistinism. He writes about him such an epitaph as would be appropriate to Mencken hunself. "It was precisely such hollow tosh " he writes "that he stood against in his role of critic of art and life; It was by exposing its general hollowness that helifted himself above the general." But where did Hunethat I remember. Certainly not in the new volume of letters which has just been published by Scribners. In these last we find Huneker living calmly, in bland indifference to the Philistines. He can scarcely be thought of as dwelling in contemporary America at all. His real home was the kingdom of Music and his head was a cave of sweet winds. He was full of all the fine things which men had written or painted or composed, not of the ignobilities of the Philistines who could not appreciate the fine things.

These letters—thouch few of them are really intimate-give an extraordinarily attractive picture of Huneker as an honest, candid, courageous and spontaneous man. He had a gift for brilliant and pithy writing which is here sometimes seen at its best. Even his letters were shot with those bright shifting colors which we already knew in his books— colors of a singular clarity, clouded, crystalline or flushed. His books were like the floral bombs and the close-packed rockets of fire-works. When they exploded we all held our breaths and were caught up for a moment to the sudden cluster which opened green and red corollas in a shower of golden gouts. If the sparks fadd out in the sky and left no that that fiery beauty had not left its color in our hearts.

Maupassant Restored

DE MAUPASSANT is, unfortunately, an an author author who who has has always always worn rather a disreputable dress in English. In America he has become associated in our minds with those raffish de luxe sets bound in flimsy purple boards badly printed on gray Paper and alleged to belong to a limited edition of which this is number 12694. Boys at college exploring these volumes, which are to be found in every club and dormitory, have a vision of Guy de Maupassant as a glorified boulevardier reeking with Parisian lewdness and easily confused with Paul de Rock. It would be impossible entirely to convince America that he was both an exceptionally severe artist and a man of excessively somber views; but the new complete translation which Knopf is publishing under the supervision of Mr. Ernest Boyd should do much to correct the old impression. For the first time, the Conard edition is being done into English in its entirety and with the stories in their chronological order and for the first time the translationis being made by a man who is both a first-rate scholar and an expert man of letters.

The first two volumes contain the earlier and most elaborate of Maupassant's short stories—those nouvelles like Bottle de Suif and La Maison Tellier in which Maupassant, attempting to apply the rigorous and restrained formula of Flaubert, produced such a richly humorous caricature of life as for a moment made pessimism jolly. These stories are riots or the cynical as the Dickens Christmas Stories are riots of the benign. Bottle de Suif is the Christmas Carol of pessimism; En Famille the Cricket on the Hearth. One advantage which Maupassant had over all his fellow novelists of the same school; his despair never showed in his work as a thinning or deadening of life.

The Parisian Swift

A NOTHER work of the school of Maupassant has just for the first time been translated into English—the Calvaire of Octave Mirbeau (Lieber and Lewis.) Mirbeau was a most remarkable man, who has never been sufficiently known in English. Originally a realistic novelist in the genre of Maupassant and the Goncourts, he eventually became a satiric writer of the era of Shaw and the later France. He was obsessed by the cruelty of - the murder and destruction which are the obverse side of life and creation and his later books are homicidal nightmares which nonetheless have an extraordinary moral dignity. Mirbeau is the great protest against the pain which inevitably attends the march of power. He is the cry of horror and disgust which Nietzsche will never let us hear.

In Calvary this theme is sounded almost on the very first page in the scene where the sober kindly doctor is shown wantonly shooting the kitten and is thereafter developed in the Franco-Prussian War and in the harrowing love affair of the hero. The war part is very good-in our own Three Soldiers vein-but I do not care much for the love affair: as not in frequently happens in Mirbeau, the banality and crassness of the characters seem to make the writing ugly and un distinguished. The glamor of the artist gives way and leaves only the stark fury of the prophet. The first part of the book, however, has always seemed to me rather interesting and attractive. It has some of the charm which seems invariably to hang over all recaptured memories of childhood and it presents a striking feature of Mirbeau's work which I have never seen properly acknowledged. For Mirbeau, without knowledge of Freud, had already reached Freud's conclusions. He had already formulated a doctrine of repression and begun to explain neuroses on its basis. His novels furnish an accurately described gallery of Freudian types. In Le Calvaire the mother of the hero is shown as suffering from such a neurosis and the hero's own downfall and mania is-though less convincingly— ascribed to a similar cause.

Mirbeau himself was a species of hysteric and at his worst represented the hysterically—as a delirium of the slaughter-house and the brothel in which nothing but lust and cruelty could survive. yet at his worst he commands a certain respect which we do not feel for many more pleasing writers of more sense and better taste. His fury, at its most hysterical of after all the saeva indignatio. If he had only had more retraint, he might have been the Swift of our time. And, as is, Le Jerdin des Supplices is our nearest equivalent to Gulliver's Travels.

It may be said in closing that Miss Margaret Widdemer's parodies, now collected under the title of A Tree with a Bird in It (Harcourt), contains some very clever things. Among a number that are silly or flat—she apparently had to do too many of them—there are not a few which are to literary skill a sort of penetrating feminine malice. Her burlesques of her sister poets are what is known among women as "catty." She gets behind the poetic mask of her victims and sticks pins in the vulnerable spots of the women. I enjoyed also her Frost, her Weaver and her Stephen Vincent Ben6t.

(On page 118 will be found a list of books which Vanity Fair recommends as especially fitting for gift purposes.)

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now