Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowWorrying at the Bridge Table

Showing That Composure at Cards Is More Advantageous Than Apprehension

R. F. FOSTER

THIS is the time of year for making good resolutions with regard to the coming Winter's bridge. Thousands of players are probably promising themselves to quit overcalling their hands; to pay attention to the score; to watch the discards, and to learn all the latest conventions. But no matter what good resolutions may be made, bridge is a temperamental game, and human nature must have its way.

There is one resolution, however, which this magazine would suggest as the best possible for the budding bridge player to begin on, and that is to join the Don't Worry Club. It is quite the correct thing now-a-days, if not to practice, to profess a profound belief in some of these psychological systems for the relief of mental strain.

It is said that nine-tenths of the worry in this world is over things that will never happen, or that could not be helped if they do. The same is true of bridge. It takes about three years for the average player to learn that although there are four suits in every hand dealt, he seldom has anything to do with more than two of them, and all the worry he puts upon the other two is just so much nervous energy wasted.

Give the average run of everyday, play-only-for-fun woman, five clubs to the ace king queen; ace king jack of diamonds; ace queen ten of spades, and two small hearts, and she will bid a club every time. Why? Because she cannot take her mind off those two small hearts, which conjure up visions of terrible losses if she should bid no-trumps. The fact that such a hand is four or five tricks above the average is nothing to her. She is blind to everything but those two little hearts.

Most of the mental worry in bridge is over the play of the cards. If one could only pick out the essential elements in each deal as it comes along and let the rest take care of itself, it would soon be found that the concentration upon the really worth while points of the play would result in a clean cut, straightforward game, which would not only bring better results financially, but greater intellectual pleasure.

Some writers call this "elimination." The idea is to eliminate from consideration, in the play of the hand, everything which no amount of thought or worry can alter, and to keep the mind fresh for the one or two things which are amenable to management of some kind. If you can't help it, don't worry about it.

It was my privilege to sit behind one of these worriers at Pinehurst last winter. It was a set match between two married couples, and the lady whom we shall call Mrs. Worry spent at least three-quarters of the time worrying about things over which she had no control, or which did not matter, or had nothing to do with the situation.

She would spend a minute or two thinking about things that should have never been given a thought, trying to work out the probable consequences of the most impossible plays, until she had forgotten all about what had already been played, with the natural consequence that she would repeatedly overlook some simple straightforward play. In one hand she thought so long about whether she had the best club or not that she forgot to take out the losing trump. I made notes of four of the hands, each illustrating a different phase of elimination. Her opponents, Mr. and Mrs. Ruffitt, were just average.

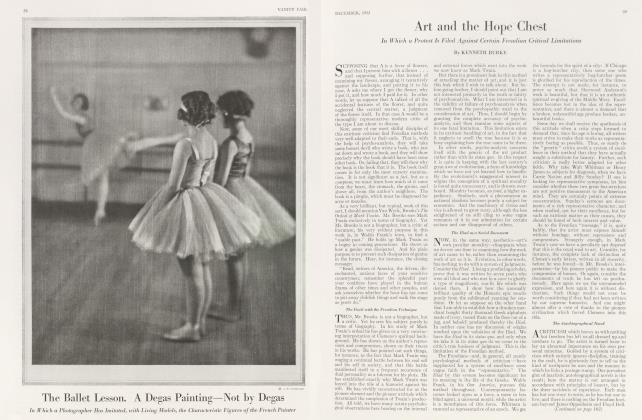

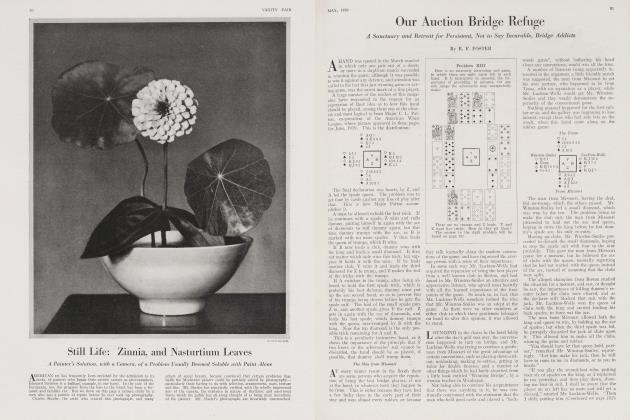

There are no trumps and Z leads. Y and Z want five tricks. How do they get them? Solution in the January number.

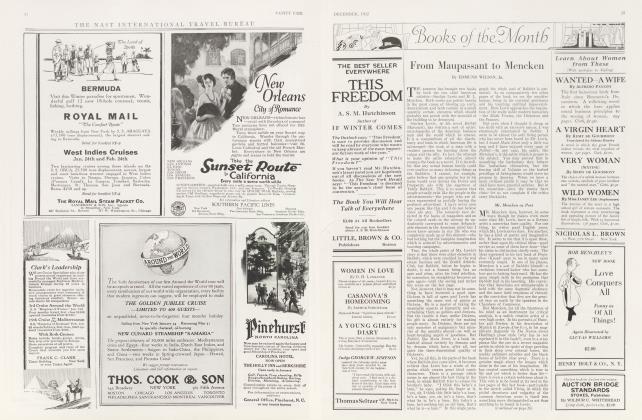

Mrs. Worry dealt and bid no-trump, which all passed. The king of hearts was led. Dummy and third hand played small cards, and the worry began. After the hand, I ascertained that this was the process of thought.

If the declarer wins the first trick, the heart suit is still stopped with the ten. Now, is it better to play the two top clubs first, to get out of the way of dummy's king, or to go right to the spades and then lead diamonds. If the diamond finesse loses, Mr. Ruffitt will be in and will have to lead up to the guarded ten of hearts. She finally concluded to make her two clubs first and then lead the spade, coming back with the diamond jack.

When the queen went up second hand, she won it with the ace and led back another diamond. The king won, and a heart came through. These five tricks saved the game.

Now there is nothing to think about in this hand, and nothing to do but to sit still and let them lead hearts until both ace and ten are good for tricks, no matter where the final heart lead comes from, because unless the declarer can make two heart tricks, game is impossible by any play. If they quit the hearts, the diamonds will be established while the declarer, still holds the top heart. The lead, against a no-trumper, looks like kingqueen-jack; but if it is not, and the jack is with the leader's partner, game is impossible if Mr. Ruffit has a high diamond, so why worry?

Here is an example of thinking so long about the wrong thing that the simplest thing is overlooked.

Mr. Worry dealt and bid a heart. Mrs. Ruffitt passed and Mrs. Worry denied the hearts with two diamonds, which induced Mr. Worry to try a no-trumper, only to have his partner go back to three diamonds.

The opening lead was the ace of clubs, followed by a small one, dummy winning with the king and Mrs. Ruffitt showing out of the suit. Now the worry began about getting out the trumps, so as to prevent Mrs. Ruffitt from over-trumping dummy on the clubs, and also so as to protect the hearts. This is worrying about nothing, as the only thing that can overtrump dummy is the ace, and there is no way to get the hearts into the lead after the trumps are gone. In the worry about the clubs being over-trumped the dangerous spade suit and them ipossibility of putting dummy in with a heart were completely overlooked.

There is nothing to think about in this hand but the fact that if the hearts are to be made at ail, they must be made now, and three losing spades can be discarded on them. After that, the declarer can trump spades, and dummy can trump clubs, and it does not matter who has the ace of trumps or what happens. The rest of the hand will play itself.

As actually played, leading the trump, three spades were made immediately, which set the contract. Had the hearts been led, the game would have been won, as dummy cannot be over-trumped.

Here it is a hand that required a little more thought, but it should have been concentrated on one thing, instead of wandering about over three different suits.

(Continued on page 112)

(Continued from page 74)

Mrs. Ruffitt dealt and bid no-trump, which all passed. Mrs. Worry, after cudgelling her brains to remember whether it was right to start with the ace of a suit headed by ace-jack-ten, or the jack, when you have a re-entry, finally concluded to lead the jack. The declarer won this with the king and led a small club.

The ace took this trick. Instead of thinking about the coming play, Mrs. Worry began to apologize to her partner, saying she knew she should not have done something. Whether she meant that she should not have won the club, or had opened with the wrong suit, her partner was left to guess. Now the worry begins.

If she leads the ace of hearts, that queen in dummy will be good for a trick. Would it be better to lead through those diamonds, or to start the spades? The dealer cannot hold all four honors in spades. Why not try to put her partner in and see what he has? Her hearts are no good, as she has lost her re-entry. The end of the cogitation was to lead the ace of hearts and then a diamond, which gave the declarer the game.

At the third trick, the only thing to think about is that although there is no reentry for the hearts now, the partner may get in, and if the partner has three hearts the game is saved. If not, nothing can save it. The play, therefore, was to lead a small heart, let the queen make, and await results. This would have held the declarer down to the odd trick.

Here is the deal in which I was particularly interested.

Mrs. Ruffitt dealt and bid a diamond; Mrs. Worry a heart; Mr. Ruffitt two diamonds, and Mr. Worry, two spades, the dealer going to three diamonds, which Mr. Worry doubled.

Mrs. Worry led two rounds of hearts, on which her partner showed down and out. This looks as if it invited a ruff, which would indicate he could over-trump dummy. But then he would have to lead up to the guarded king of spades, or up to the ten-ace in clubs.

It took about a minute and a half to decide whether to lead through the clubs, or give partner the ruff in hearts, or put dummy in by leading two rounds of spades, or to lead the trump and make the declarer start something. The decision was to give her partner the ruff, and he led the trump, so as to get a lead up to his club king.

The declarer pulled both Mrs. Worry's trumps and led a club, putting on the ace and trumping the return, killing the king. Then the declarer led a spade through, and Mrs. Worry went up with the ace; but lost every other trick, as dummy still had a trump left for the hearts, and the declarer got a spade discard on the club jack. This won the game; three diamonds doubled.

At the third trick, had Mrs. Worry given her exclusive attention to one point in the game, she could have set the contract for 300 points without any effort at all. As the situation is both interesting and instructive, readers of this magazine may like to figure it out for themselves. The key to the play is simplicity itself.

Answer to the November Problem

This was the distribution in Problem XLII, which readers were warned was full of pitfalls:

There are no trumps and Z leads. Y and Z want two tricks, in spite of any defence. This is how they get them.

The only possible solution is for Z to lead the diamond, upon which Y must discard the club. There are now three lines of defence. The best is for A to lead a small heart, which Y passes, allowing the queen to win. On this trick Z must be careful to play the eight, or A can defeat the solution.

B now leads the ace and eight of clubs, A overtaking the eight and leading the queen. On these club leads, Y discards all three of his spades. Now Y must make two hearts, if he passes up the ten in case A leads a high one. This is the straight solution.

But B may lead the eight of clubs, instead of the ace, for the third trick. Then Y discards a heart, instead of a spade, whether A overtakes the club or not. Y can then force B into the lead later with a small spade, if A overtakes the club and leads a heart; or must make a spade if the club eight holds.

A may vary the defence by leading the nine of clubs at the second trick, instead of the heart. Y discards a spade. If B wins the club and returns it. B may win the club and return it, and Y will discard another spade. Now if A leads the third club, Y gets rid of his last spade; but if A shifts to the hearts Y puts on the ace and Z keeps the eight, which will hold the next heart lead, or force A to lose a heart trick to Y's seven.

If A leads a club for the second trick, and B leads the queen of hearts before returning the club, Y will let the queen hold, Z giving up the eight. Now B must lead the clubs and Y sheds all his spades, making two hearts at the end.

There are several alleged solutions to this problem which are unsound, as they overlook the intricate and beautiful manipulations of the club suit. For instance; If Y discards a spade instead of the club on the first trick, A will at once lead a small heart, which goes to B's queen, and B returns the eight of clubs. A wins it and leads the ten of hearts. If Y puts on the ace, the solution fails right there. If he passes, B sheds the ace of clubs, and A leads the trey, of clubs, putting Z into the lead with the five.

(Continued on page 114)

(Continued from page 112)

If Z does not give up the eight of hearts on the second trick in the main variation, when B wins with the queen, A will win the second round of clubs and lead the six of hearts, which sets up the suit for A, or throws Z into the lead with the eight,

If Z starts the play with a club, the defences are very ingenious. A plays the nine, B overtakes with the ace and leads the heart. Y must let this hold, Z giving up the eight. If Y wins the heart he must lose two spade tricks, after which A makes two hearts, a club and a diamond, If Y returns the heart A makes the ten and nine and then puts B in with the trey of clubs, so that so that B can make the top spade, upon which A discards the losing heart and gets in on the diamond to make the third club.

Forseeing this, if Y refuses to win the heart queen, B shifts to the diamond, Y discarding a spade, and A leads his top heart. This Y must pass, or lose every other trick, B sheds the eight of clubs, and Z finds himself in the lead on the next trick when A leads the club three.

If Y does not discard the spade on the diamond in this variation he gets down to two hearts, and when A leads his top heart, Y must win it, or let A lead again, and all the time B is holding the eight of clubs, so as to give A the lead again, after B has made his two spades. The importance of A's retaining the three of clubs, so as to compel Z to lead spades in certain variations, is one of the most elusive features of this remarkable problem. It is the key to the defence, if Z starts with the eight of hearts, instead of the diamond.

In this variation, the heart queen would, win the first trick, and the ace of clubs leaves A with queen and trey. A diamond puts A in, and the ten of hearts follows, If Y, who has discarded a spade on the diamond, refuses to put on the heart ace, B sheds the club eight, and the trey of clubs puts Z into the lead. If Y has kept three spades, B will keep the club, as Y must win the fifth trick with the ace of hearts.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now