Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Difficulties of the Discard

Some Modern Conventions, Designed to Show the Partner Which Suit to Hold

R. F. FOSTER

THE difference between discarding at bridge and discarding in the average run of card games is that in such games apoker, piquet, and pinochle the player discardon hiknowledge of probabilities and his willingness to gamble on what he will probably draw in place of his discard. In bridge, discards arc based on inferences as to what the adversaries hold, and upon the player's judgment of what he can afford to risk by unguarding one suit in order to make a possible extra trick or two in another.

Some years ago there was a rather heated discussion on the subject of discarding when opposed to the declarer, the net result ot which was to formulate the maxim that is safer to discard the suit you are not afraid of. 1 his was based on the common-sense principle that if vou have two suits, one headed by ace and king, and the other by a jack, it is not the aceking suit that is going to be led after you have made one or two discards.

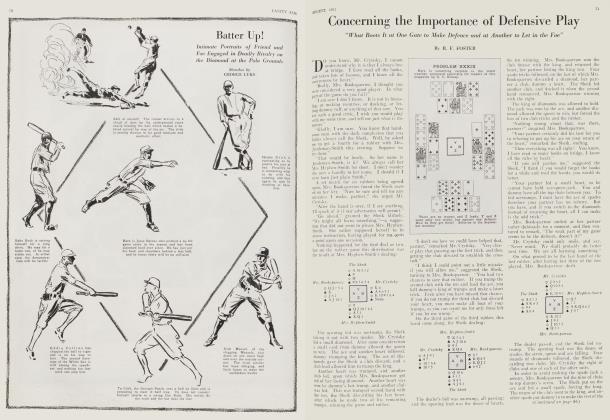

No player likes to surrender one or two possible tricks by discarding what would be sure winners if he could get into the lead with them; but the question is getting into the lead bv -topping the third suit, after discarding on the second. Take this example:

Z was playing the hand at no-trump and won the first heart trick. He then proceeded to make five diamonds, upon which B incautiously discarded a small heart and then a club, so that the declarer made four odd and game, instead of being stopped at two odd.

THERE is nothing to guide one in many cases, such as the foregoing, except the general principle of protecting the weak suits, if possible. Jack in one hand, queen in the other, either twice guarded, will stop any Suit, no matter how it is led or played. The most annoying thing about discarding, however, is for both partners to be protecting the same suit, and both losing every trick in a suit that they might have kept guarded.

It is to avoid this that modern players have adopted a system of conventional discards which shall show the partner the suit they can protect, and leave him free to discard it, and protect the other, if he can. These conventions are useful under two conditions only; that the partner understands them, and that he notices carefully the small cards that fall to each trick.

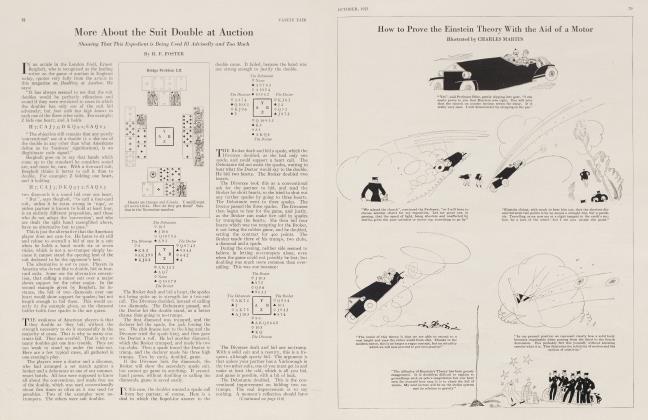

The convention more commonly used is called the encouraging discard. This is the discard of any card higher than a six. The object is to let the partner know that he need not worry about that suit. Here is an illustration of it in action:

Z is playing the hand at no trump, and A leads the jack of diamonds, which Z wins with the king, to conceal the queen. He then runs off five winning clubs. On the second club lead A discards the encouraging eight of spades, and then the small hearts. This relieves B's mind as to which of the major suits to discard. As he must keep the diamond to lead to his partner, he discards two spades on the clubs. 11 B is left to a guess, he might let go two hearts, which would give Z the game. To discard the small heart and then a card as high as the nine of spades might mislead his partner.

A variation of this convention consists in making two discards in the same suit if the opportunity presents itself. This is often useful when there is no high card available that would be large enough for an encouraging discard.

The reverse discard consists in reversing the usual order in which two consecutive discard.' would be made by shedding the higher card first, which is a sort of down-and-out echo. Some placers restrict this discard to cases in which thev have a certain winner in the suit, no matter who leads it; others again keep the reverse discard as a command to the partner to abandon his suit and lead the one indicated.

In the foregoing hand, A might have indicated that his spade protection was the ace by discarding the eight and then a smaller spade; but that might possibly be taken by the partner as a command to lead spades it he got in, instead of returning the diamond.

A might also have shown the sure trick, as distinguished from such a holding as the king guarded, by discarding the five and tour, but A has no certaintv that he will have an opportunity to complete the reverse before a shitt in suits, so he makes sure of the situation by discarding the eight, and then letting go a heart, instead of completing a reverse.

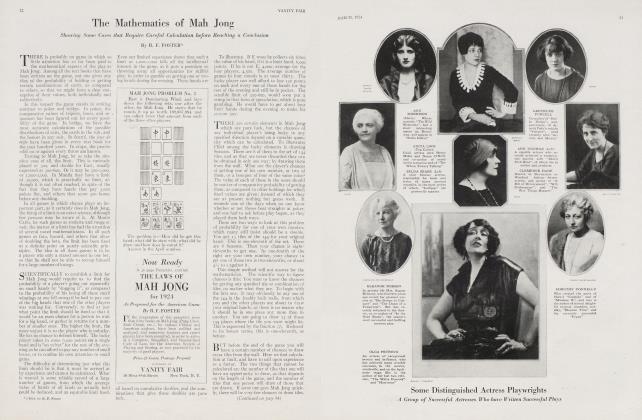

THOSE who use the reverse as a command to the partner to lead the suit indicated should be verv sure of their ground. Here is an example of such a situation, taken from Modern Hridge Tactics:

Z is playing the hand at no trump, and A leads the live ot spades, which Z wins with the king, and immediately leads three roundot diamonds, A winning the third. On these trick B makes a reverse discard in club' with the nine and deuce, telling A to abandon his spade suit and lead a club. This shift set the notrump contract for two tricks.

If A is misled by Z's play on the first trick, and takes a chance that B has the spade queen, or if he tries a supporting lead through the king of hearts, so as to keep his guarded king ot clubs, he loses the game before the declarer lets go of the lead.

There are many cases in which the only guide as to the proper discard is the player's judgment of the situation, without any assistance from his partner's use of conventions. This requires a degree of skill not possessed by every player, of course, but it is remarkable how many cases there are in the course of an evening's play in which the suit discarded shows the suit kept.

Not only is this true of the adversaries, but it is often the only guide for the declarer, who inucn discarding as any other player, and often must be even more careful about it. Take this case:

(Continued on page 106)

(Continued from page 75)

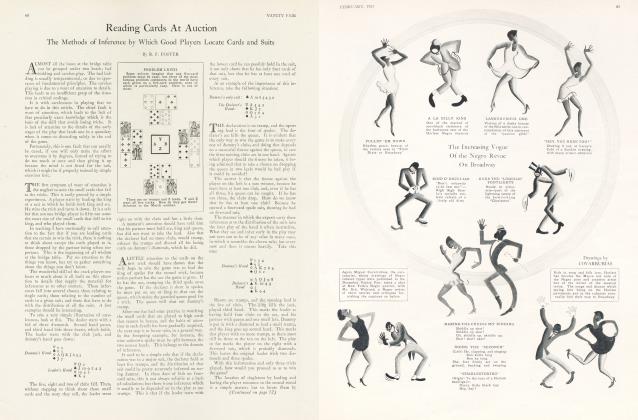

Z is playing the hand at no trump. A leads the king of diamonds, which Z wins, and runs off five club tricks. On these tricks A discards two of his own suit before his partner gets a chance to complete a reverse in spades, so A lets go another diamond, his spades being apparently just as good as the diamonds, if his partner has the spade king.

Z notes these discards, and infers that A must have both the major suits stopped, and did not know which to keep. As the only possible stopper in hearts must be the king, and there cannot be two guards to it, or A would let one of them go, Z leads the heart queen, and allows A to make his remaining diamonds.

No matter what A does next, the ace of spades gives Z a finesse against the jack of hearts and the ace of that suit wins the game.

There are many cases in which the declarer has to watch his step or he will miss tricks, games, and slams that he might otherwise have made. Here is a case in which carelessness in discarding missed a little slam:

Z dealt and bid a heart, A two dubs and Y two spades, which held. B led the club and dummy won the trick with the ace. A small trump was led, and the finesse of the jack held. With the idea of discarding his two losing clubs Y led the king of hearts, overtook it with the ace and discarded a club on the queen of hearts.

When dummy led the jack A trumped it, and Y had to overtrump. Then he pulled the king, leaving dummy with the seven of trumps for a reentry for the hearts. At this stage it dawned on Y that his club discard was a mistake, and that he should have let go a diamond, and kept a club, so that after losing a club trick he would still have a club to lead from his own hand for dummy to trump. This would have made the little slam that Y missed.

This was the last of the hands given in the August number, in which the Russian expert made a little slam:

Y gets the contract in spades, after Z dealt and bid clubs, A bidding hearts. The opening lead was the queen of hearts. The problem was how the declarer made the little slam. This is the answer:

Winning the first trick with the ace of hearts, Y led the king and ace of spades, trumps. On the second round, when B dropped the queen, A was marked with the ten alone, so dummy gave up the jack to unblock.

The jack of clubs was covered by the queen, and won by dummy's king. The ace of clubs found A void and marked B with the nine, five and four, so Y gave up the eight, to establish the tenace in dummy.

Now dummy leads the eight of trumps, and Y wins it with the nine and leads the three of clubs. No matter which club B plays, dummy wins and make two more club tricks, giving Y two diamond discards, so that the only trick lost is a heart at the end.

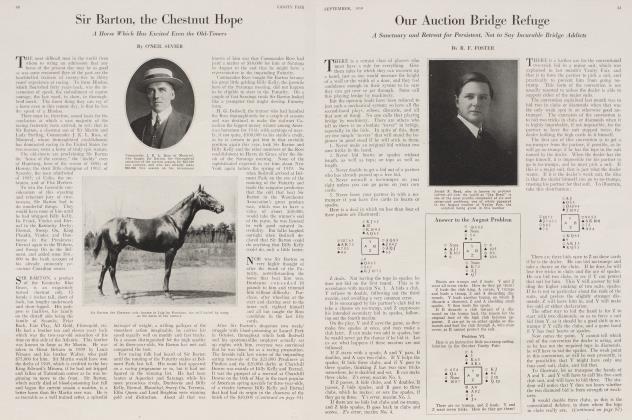

ANSWER TO AUGUST PROBLEM

This was the distribution in Problem LXXIV:

Hearts are trumps and Z leads. Y and Z want all the tricks. This is how they get them:

Z starts with the ace of diamonds, all playing small cards. The next lead is the three of trumps, which Y wins with the seven, B's discard being probably a club. Y then leads the jack of diamonds, which B must cover and Z trumps. Z leads the trump, A and B both discarding clubs 5 Y the spade jack.

Z now leads the club, which Y wins with the queen. If A lets go a diamond, Y can lead the ten of diamonds, forcing the king from B, which Z will trump, and Y gets in •with the ace of spades to make a trick with the five of diamonds.

If A discards a spade instead of the diamond, and B discards a diamond, Y can lead the smaller of his two diamonds, forcing B's king, and then Y's ten is good for the last trick. If B lets go a spade when A discards a spade, Z will make a trick with the deuce of spades, as Y will lay down his ace of spades before leading another diamond for Z to trump.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now