Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowOur Auction Bridge Refuge

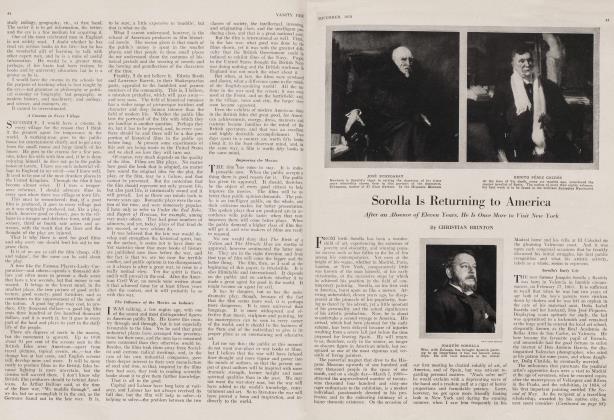

A Sanctuary and Retreat for Persistent—Not to Say Incurable Bridge Addicts

R. F. FOSTER

ONE of the situations in which the average player is inclined to be rather loose, in his system of bidding is fourth hand to an original no-trumper. If any bid is made in such a position, it should have one of two objects; to drive the no-trumper into a suit in which it will not be so easy to win the game; or to get the best opening lead in case of a return to no-trumps.

The minimum for this position should be a five-card suit which is not solid, but which will probably clear in one round if the partner has any honour to lead, or can lead through an honour in dummy, and a reentry. If four cards out of the five win tricks, the reentry is the fifth that saves the game. It is useless to call a solid suit, asking for a lead, as that simply switches the no-trumper to safety. Here is a typical case of an ask for a lead, fourth hand:

Z deals and bids no-trump. . B asks for a diamond lead, bidding two. This forces Z to shift to clubs, or take a chance on two notrumps. On the chance that he can drop all the clubs, he goes back to no-trumps.

Z lets the ten of diamonds hold. Two more rounds clear the suit for B. The clubs fail to drop, so Z tries the spade finesse, the jack forcing the queen. Dummy leads a heart, and B is in to make his two established diamonds, saving the game.

If the diamond lead is not asked foiyZ goes game by winning the spade, opening with dummy's ten (eleven rule). Finding the clubs do not drop, he clears the hearts. Three clubs, three hearts and three spades win the game, independently of the diamond suit, B losing his reentry before his diamonds clear.

If B is left to play the hand at diamonds, he will be set three tricks, less 28 in honours. If not doubled, this will cost him 122 points. If doubled, 272. The loss of the rubber would have cost him 280.

"IT must be just lovely to know so much about bridge, Mr. Devest, that every one is afraid to play with you," gushed the young debutante. "I should so much like to have a rubber with you sometime, but I would not dare."

Mr. Devest puffed at his cigarette thoughtfully for a moment, trying to recall any occasion upon which he had even suggested playing with her. Feeling that he had to say something, he had an idea.

"I am afraid you overrate my skill. Luck is a much more important element, and I fear we should not pull together very well."

"What makes you think I am unlucky," she beamed, with the coveted rubber almost in sight.

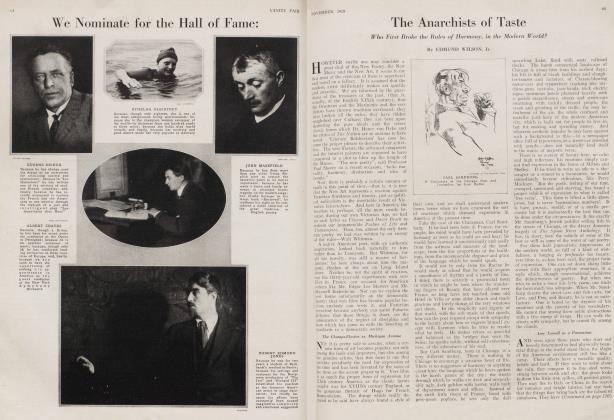

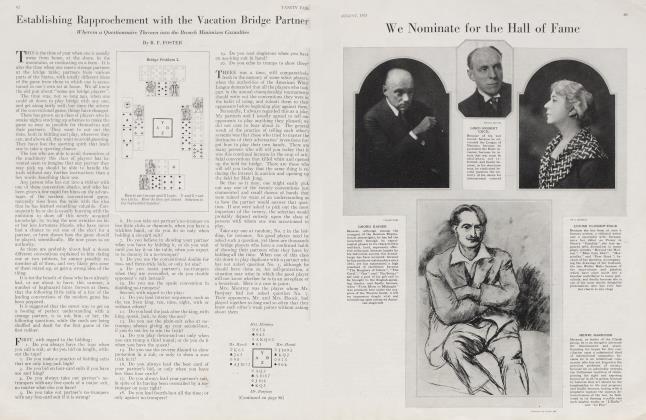

Problem XVIII

Hearts are trumps and Z lbads. Y and Z want all eight tricks. How do they get them? Solution in the November number

"Success in cards and in love seldom go together, you know."

"Now stop talking nonsense. Let us challenge that wine-agent; I forget his name, and his partner, the tennis player. They are always boasting about their game. I should just love to take them dovm a peg."

"You have picked the luckiest card player I ever met. If I had that wine-agent's luck, I should spend the rest of my life in Wall Street."

That afternoon, the debutante persisting, the match was duly arranged, and started with high hopes; but, after a couple of hours, Mr. Devest and his partner were quite willing to call it off and settle up. He was more than ever convinced that the wine-agent was the most extraordinarily lucky man he had ever seen play auction.

Talking over their ignominious defeat after dinner that evening, Mr. Devest, whose memory of games was remarkably good, became reminiscent.

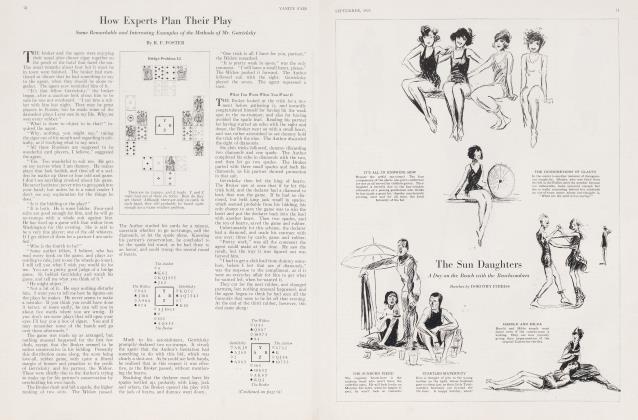

"Do you remember that hand when you called a lead, and I told you afterwards that it was not the right penalty ? Well, that cost us the rubber, instead of netting us two hundred in penalties. He did not know enough to deny your right to call a lead, and gave us a great chance. It was his amazing luck that finally saved him. Let me show you the hand." Sorting out the cards, he explained the play. Here is the distribution, and the way things went:

Mr. Devest dealt and bid a club, the tennis player a spade, and the debutante two hearts, the wine-agent two no-trumps, which the debutante doubled. As the no-trumper seemed to deny any assistance in spades, the dealer led the deuce of that suit. Dummy played the trey, the debutante discarded the eight of hearts, and the wine-agent studied the trick for a moment, as if he did not quite grasp the situation, finally remarking, "Dummy's trick, eh?" This being agreed to, he played the four, and immediately led a small spade from dummy.

"Wrong hand!" exclaimed the debutante, gleefully. "Lead a club." Not knowing the rules, he led the jack of clubs, Mr. Devest putting on the ace and returning the suit, imagining his partner could get in on that suit. The result was that the wine-agent made the rest of the spades, then another winning club, and finally a diamond. By that time, the d6butante was down to three hearts and the two top diamonds, and had to give dummy a heart trick. Two by cards, doubled, game and rubber for the wine-agent.

"If you had called a diamond, instead of a club, you would have got into the lead at once," Mr. Devest explained. "Then you can give him a heart trick, and let him make his spades. He is down two hundred, whatever he does next."

"I thought as you bid the clubs, you could win that trick and then come through the king of hearts. That is why I. called for a club. I wanted you to be in the lead. How should I know you had no hearts?"

Without explaining that his opening, lead showed this, he proceeded to lay out another hand. "Here is a deal that cost us a thousand points."

"Was that my fault, too?" she asked wofully.

"Not a bit of it—at least, not exactly. It was his luck in not sorting his hand properly, and making a bid that kept you from leading your strongest suit"

(Continued on page 92)

(Continued from page 81)

The tennis player dealt and bid a club, A passed and Y, who had the ace of diamonds with his hearts, bid one heart, the debutante a spade. The dealer assisted the hearts and Mr. Devest went to two spades, the wine-agent going to three hearts. This the debutante doubled, and the wine-agent shifted to three no-trumps, which was also doubled.

The opening lead was a small spade, which the wine-agent won with the king. A club lead brought down the king and the ten of diamonds held. Another diamond and the jack held. The wine-agent was evidently disconcerted about something. Before he turned the trick down, he remarked, "Won't give it up, eh?"

Putting the club through again, he led another diamond from dummy, dropping the queen, the debutante renouncing. This caused him to go through his cards again more carefully, with the result that he found the ace of diamonds in his own hand. "Sorry, partner," he apologized, "I had that ace of diamonds among my hearts all the time."

"Isn't there a penalty for naming cards in your hand?" demanded the debutante quickly.

"Not against the declarer. He can expose his cards all he wants to," her partner assured her sadly.

"Then I can go ahead?" remarked the wine-agent, and on being told he could, he proceeded to make all five of his diamonds, three clubs and the spade, giving him game and rubber.

"Had you opened your best suit, hearts," observed Mr. Devest, in showing her the hand, "whether you lead the ten or a small one, I put on the ace and lead the spades, as you bid spades, and he gets only three tricks on a contract to win nine. We score 600 penalty, instead of giving him 360. The difference is about a thousand, yet some people do not believe in luck. Let me show you another hand."

"No, thanks. I've seen enough. I suppose there is something in luck after all."

AMONG the most interesting situations at the bridge table, probably some of the least understood are developed from what are technically known as secondary bids. These are invariably suit bids, and are made on long and weak suits in hands that are good for little or nothing, unless that suit is the trump, the suit having no defensive value.

The old way was to start such hands with a bid of two. Apart from the unwisdom of giving such information to the adversaries, this system was soon shown to be unsound in principle, because it was undertaking a bigger contract with a weaker hand,—offering to win eight tricks with cards that did not justify a bid to win seven.

Apart from these two Considerations, such bids had the vital defect of being ambiguous, because the same player would bid two on a suit that was above average in high cards and length. If we are going to bid two originally on long weak suits, we must cut out the two-bid on very strong suits, or the bid will have a double meaning, which is fatal to good team work.

All this is avoided by relegating all these long weak suits, useful only as trumps, to the class of secondary bids. These bids may never be made, unless the situation develops favorably, and in any case the partner is never deceived by them. The rules governing them are very simple.

Do not assist a secondary bid unless you hold one or two high honours in the suit, and do not lead such suits if you have a good suit of your own, yn. less you have honours in the secondary, bid suit.

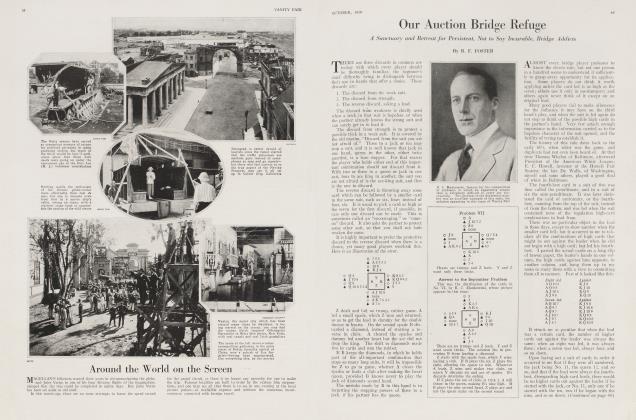

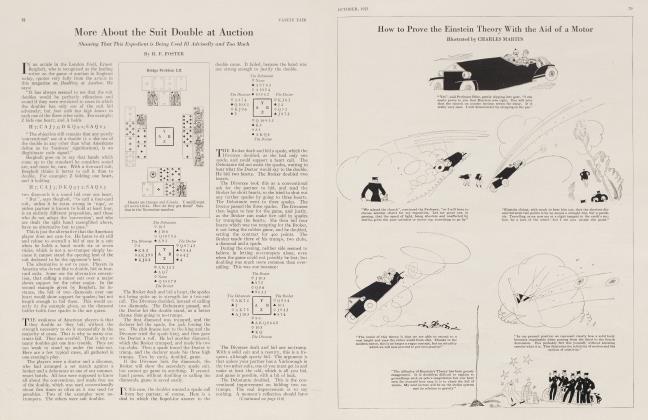

The following deal, which came up in a duplicate match, will admirably illustrate the difference between the old school of playing and the new, and also the importance of the partner's proper understanding of the response to secondary bids:

Z dealt. At the table at which he played—believing in the old style of bid —he declared two spades, A three hearts, Y three spades, which B doubled. Now we find the weakness of the original bid when it is from length only. There is no way to jump, so Z has to pass. A cannot rebid the hearts after his partner has refused to assist him, so Z is set for 118 points.

A led one round of hearts and then the club, through strength. When dummy led the trump, B put on the queen, losing to the king. Z put dummy in with a diamond and led another trump, which B won, leading the queen of hearts and then a diamond. This Z won, leading another club, so as to get a third trump lead through B, and save the ten.

B won the trump and led the queen of clubs, which Z trumped, losing a diamond trick at the end. This shows that, although the original bid was good for the contract, two odd, (the partner, fortunately, having more than average assistance), the assist is, nevertheless, a mistake, because it is based on a mistaken estimate of the strength of the spade suit.

At the tables at which the hand was correctly bid and played, Z passed, and A bid the hearts. Y and B passing, Z now bid the spades. B assisted the hearts, bidding two, but Z declined to go further, and Y then refused to assist him,, as he had no honours in the spade suit.

At one table, Y took a chance on two no-trumps and was set two tricks, as B led the queen of hearts and then started in to kill dummy's reentry in diamonds. B won the first spade lead with the ace, and Z let him hold the second with the queen, thereby losing three hearts, two spades and two diamonds.

When A was left in on hearts, Y led the club king, as he had no honours in spades, and on Z's dropping the eight, he went on, got the echo and gave Z the ruff. Z laid down the ace of diamonds to make sure of saving the game, got an echo with the nine and then went on,—after which the jack of hearts made another trick. And this set the contract.

If Y is not familiar with the tactics of leading to secondary bids, he will start with a spade, and A will make his contract. Dummy plays the queen second hand, covered by the king and trumped. Now the ace and jack of spades give A two diamond discards later. The ten of spades may be allowed to hold,—which gives A another discard, A putting B in by leading the king and then a small trump, for the purpose of getting the spade discards early.

(Continued on page 94)

(Continued from, page 92)

Answer to the September Problem

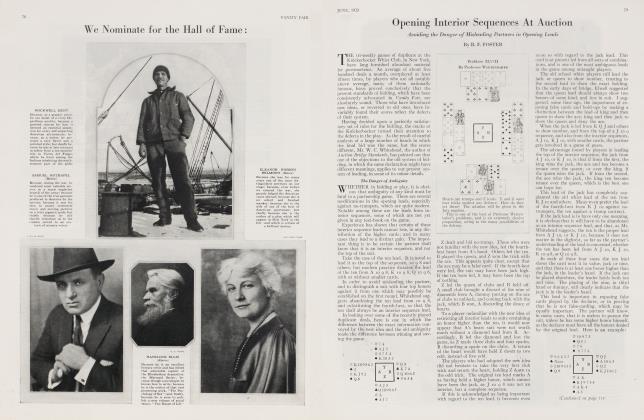

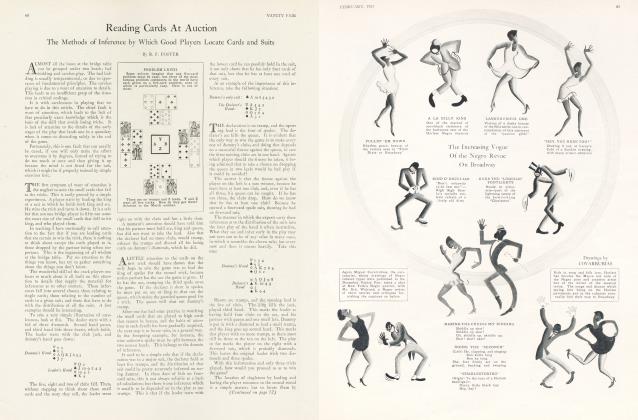

HERE is the distribution in Problem XVII, by S. C. Kinsey:

Hearts are trumps and Z is in the lead. Y and Z want all the tricks.

Z starts with a trump, and A passes it up, as the best defence. Z follows with the best club and the best spade. If A trumps the spade, Y over-trumps, and takes out A's last trump, Z discarding the ten of diamonds; Y then leads his fourth trump, and Z regulates his discard by B's.

If B keeps the spade, Z discards that suit, and A will have to give Y three diamond tricks or make the nine of clubs good in Z's hand. If B lets the spade go, Z sheds the nine of clubs, and makes a spade and a diamond; Y making another diamond at the end. If B has discarded two diamonds, the ace kills the queen, and Y makes the king and eight over A's jack and six. This is the situation provided for by the diacard of the ten of diamonds.

If A discards a diamond on the ace of spades, instead of trumping it, Z must lead the losing club immediately so as to prevent a second diamond discard by A. Then Y will trump the club and lead two rounds of diamonds, king first. This leaves Y with the major ten-ace in trumps over A at the end.

If A covers the ten of trumps on the first trick of all, Y wins and leads a club, allowing Z to lead the ace of spades. If A trumps, Y over-trumps, and the ending is the same as before.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now