Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Dramas that Bloom in the Fall

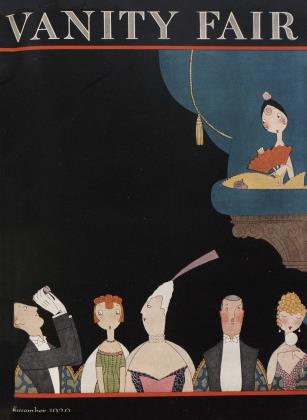

Picking the Early Blossoms in New York's Theatrical Garden

GEORGE S. CHAPPELL

WE are now in the spring of the theatrical year. There is something fascinating to me in the topsy-turvy customs of the dramatic calendar. To the managerial heart, September brings the first flutterings of April-like moods and fancies, the clear days of October see him tenderly nursing the little dramatic May-flowers which have pushed their shy heads through the mould, while his midsummer is the coal-man's winter.

And though this reverse order of the sequence of months is a little confusing, it will be seen to have a law of its own, as simple and fundamental as other laws of nature. When, for instance, the managerial eye notes that the young ladies of the chorus have been sun-burned to a particular cordovan shade of brown, he knows that vacations are almost over. When the managerial scouts report that there is an ever-increasing number of black and white checked-suits and white tennisshoes among the younger histrionic athleticset, who take their daily exercise in front of the Lambs' Club, he knows that it is time to press the electric-button and get out his blank contracts.

To me there is something fascinating in the thought of this obedience to natural laws. I like to think of Lee Shubert saying to his brother, "Lissen!, J. J., I hear a chorus rehearsing. That means forty days till the first frost."

What a season of budding and burgeoning it is, this Fall-Spring of the theatrical year. How the new plays and musical shows burst about us, one, two, sometimes three of an evening. Of course, it is utterly impossible to keep track of them all. The most ardent theatregoer can only be in one theatre at a time, and the selection is not always easy. It is like one of those embarrassing menus which gives you a choice between a multitude of dishes, all of which sound perfectly delicious. You swing painfully between steak-minute, and chickenpie; finally, you order steak and then suffer tortures of remorse when the man at the next table receives a magnificent looking consignment of chicken-pie. "Why didn't I order that!" you think.

The Greenwich Village Follies

BUT, of course, there are some events in the early days of a season about which one has no hesitation.

In the forefront of this class one must place the Greenwich Village Follies of 1920, which, by virtue of the enterprise and imagination of John Murray Anderson, has added to his prestige of former years and proved the right of this production to be considered one of the big, opening guns of a new season. The G. V. F.,—we really must use initials,—is a most gorgeous thing. We all have within us a sort of semi-conscious standard of gorgeousness, and I think mine used to be a passage in the Autobiography of P. T. Barnum in which he describes the splendors of Queen Victoria's court; the tables of malachite and the chairs encrusted with emeralds, diamonds, topazes and rubies. But the G. V. F. has transcended all that.

It is primarily because of its scenic and costuming appeal that the entertainment wins out, and here let me make sweeping salutation to those two talented young men, Messrs. James Reynolds and Robert Locker who, between them, designed the lovely backgrounds and garments with which the producer has built up his colourful pictures. It would be unfair not to mention particularly Jimmy Reynolds' Russian set, in which he gradually created a pattern of colour which rivals in glow and fire the beauty of a XVth century rose-window. And just think, it was all built up around a song about a Samovar. I've got one of the tricky things up in the country; now all I need is twenty beautiful girls and some costumes and scenery.

Next to the beauty of the costumes and their contents, the success of the show depends on the thrilling dancing of Ivan Bankoff and his partner, Mlle. Phoebe, the remarkable acrobatic whirls of James Clemons and a most interesting innovation, a dance with masks, by Margaret Severn. The masks were designed and made by W. T. Benda. I should like to write a book on The Mask in Dramatic Art, but it has doubtless already been done,— probably by a German.

Like other human organizations, the G. V. F. can't have everything, so the merry villagers evidently decided to do without humour. It is surprising how humourless the performance is, —in fact, it is rather worse than that, for there are several attempts in that direction which fall with the resiliency of a cream-puff dropping from the fly-gallery. Partial success seemed to be attained by Savoy and Brennan but, to me, their act is, somehow, revolting, and I can pay Mr. Anderson no greater compliment than to say that I enjoyed myself in spite of them.

It was a joy to settle down in a comfortable chair in the Selywn Theatre and really laugh with that absurd Frank Tinney person who, assisted by Arthur Hammerstein, has put a clean hit across the plate in Tickle Me. Frank is not only unfailingly amusing, but he has surrounded himself with more than competent people. Herbert Stothart has done a sparkling score and the book, with its background of moving-picture habits makes even the conventional second-act trip to India seem almost credible. And what can be said of Tinney's ten-minute skit with Louise Allen, the 'Broadway Swell and the Bowery Bum'? Shades of Tony Pastor and Peter Daley,—the Selwyn Theatre shook with thunderous laughter in which the note of reminiscent sentiment was not lacking. In an excellent cast Vic Casmore almost accomplished the miracle of making a stage Frenchman both amusing and likeable.

"The Sweetheart Shop"

DOWN at the Knickerbocker a much more conventional sort of musical-show, The Sweetheart Shop, is displaying its wares. It is a smart and attractive line of goods which the managers offer, presented with a certain surefire method of salesmanship which at times seems rather cocky. The piece has had long preparation for its New York production and everything has been rehearsed to the limit. The dances come off just so,—there is no fumbling for lines, the pace is brisk and snappy,—but everyone seems so dead sure of him or herself that, for some reason or other, I resented it. It is really rather unfortunate to hate a man the way I did Harry Morton, the leading comedian, from the moment he appeared. I say unfortunate, not for Mr. Morton—he probably doesn't mind it at all,—but unfortunate for myself, for at first his brazen assurance annoyed me exceedingly and then, in spite of myself, I began to like him, and that annoyed me even more.

Una Fleming and Mary Harper were both sweet to look upon and listen to, but the highest honours should go to Esther Howard, whose portrait appears elsewhere in this issue, and whose-range of talent apparently extends from grotesque comedy to the possession of real dramatic ability. In the words of her own best song, 'She's Artistic'.

In Reminiscent Mood

TW'O plays which turn back the clock of time are Ian Hay's Happy-Go-Lucky, at the Booth, and Little Old New York—at the Plymouth, placid, pleasant performances both, which are cordially recommended to lovers of Dickens, Washington Irving and the household gods of other days.

It is interesting to think of the gallant Major Beith, freed from war's alarms, finding and sharing with his audience his enjoyment of the contrasted strata of English classes, though it is probable that the proud Mainwarings of todav would find the humble Welwyn family far less removed from their social orbit than in the dim period before the first Zeppelin shook London together. I hope I shall never forget O. P. Heggie's performance as Samuel Stillbottle, the gentle, visiting bailiff. Also I should like to register a prophecy; some day, in the near future, someone will star Miss Gypsy O'Brien, and New York will say: "Why, where has she been all these years?"

(Continued on page 96)

(Continued from page 51)

Speaking of prophecy, Little Old New York depends, in a large measure, for its success—on that curious trick of prophesying events which have already taken place. Just why, when Albert Andrus, as the first American Astor, says that the land around Gramercy Pond will some day be very valuable, the audience should burst into rapturous applause, is rather mysterious. But so it is. It is very pleasant to spend an evening with such worthies as Washington Irving, and Fitz Green Halleck, and most comforting to hear Cornelius Vanderbilt speak so simply of his ferry to Staten Island. Somehow it seemed to take the curse off of living in the suburbs. Ernest Glendenning plays the leading role of Larry Delevan with his usual finish, assisted by Genevieve Tobin, whose performance is somewhat marred by a tendency to coo her lines, as coos the dove.

The excellencies of a Belasco production greatly assist Jean Archibald's little comedy at the Empire, in which Janet Beecher, as a somewhat awe-inspiring matrimonial expert, smooths out various domestic tangles with an authority which appeals to the spectator's intelligence rather than to his emotions. The little play is full of brightly written scenes but, on the whole, lacks heart. I could not help feeling sorry for the handsome hero, Dudley Townsend, excellently played by Phillip Merivale, when I foreshadowed his married life with the omniscent Joan Deering, to whom, apparently, every move and motive of mankind is an open book.

One of the assignments which I should gladly have traded for two seats at the Hppodrome was the Harris production of Welcome Stranger at the Cohan and Harris. The story deals with the difficulties experienced by a supposedly engaging Jewish merchant in breaking into the hard-shelled social and business life of a New England village. Perhaps my recollection of certain Connecticut hamlets in which the old homesteads have been turned into hat-factories over night by similar invasions, has prejudiced me against this sort of thing. I can no more imagine George Sidney's Isadore Solomon as a real part of a country landscape than I can accept the cows which the late Mr. Hammerstein used to milk by electricity on his ancient roof-garden.

Hopwood, Rinehart and Co.

THAT indefatigable team of authors, —Avery Hopwood ' and Mary Roberts Rinehart offer, for our consideration, two plays of such widely contrasted character that it is difficult to conceive how they could possibly have emanated from the same minds. Spanish Love, to be sure, owes its origin to anterior sources, judging from the array of Spanish names which supplement those of our native playwrights. There is a tendency in modern Spanish painting to load the canvas with colour; something between a washboard and a nutmeg-grater. This is just what has happened to Spanish Love.

The result is not uninteresting and, were it handled more simply, would gain in effectiveness. Alas, a strange craving for innovation has induced the producers to discard the outworn devices of exits and entrances back of the proscenium arch, which used to separate the worlds of actuality and make-believe, and to substitute in their place a vague, migratory movement of the cast among the audience, with goings and comings through boxes, down the center aisle and from the orchestra pit. If this be art, why not go further and let the hero chute the chutes from the upper gallery or swing a rope ladder from the second-tier boxes.

Mention of the second HopwoodRinehart offering, The Bat, must be done with finger on lip and bated breath. It is a tale of murder, of creepy-creeps and horror, of which the surprise denouement is an inviolable secret between Messrs. Wagenhals and Kemper and the thousands of excited spectators who have already besieged the Morosco box-office. In this field Mrs. Rinehart is evidently at home and supremely successful, and her collaboration has doubtless added many of the. bright lines, a major portion of which are entrusted to the capable hands of Miss Effie Ellsler, who makes Miss Cornelia* Van Gordes an authoritative and clear-cut figure. May Vokes' Lizzie filled me with horror, but probably not of the kind intended by the authors; she seemed hopelessly out of the picture. In the main, however, The Bat is a stirring performance and one by no means to be recommended to husbands with nervous wives who are prone to hear things at night.

There can be no higher tribute to the combined prowess of a master and mistress of stagecraft than to say that David Belasco and Frances Starr, between them, manage to make One possible. It is frankly a treatise, and rather a dreary one at that, dealing with psychic communication, a subject which even imported celebrities like Sir Oliver Lodge and M. Maeterlinck failed to put across very convincingly. Yet a crowded house at the Belasco followed with rapt attention Miss Starr's marvellous performance in the dual roles of the twinsisters who had been so meanly served by fate with a half-portion of soul each. In fact, Miss Starr's artistry even surmounted the terrible fact that the two sisters' names were respectively Ruby and Pearl. Can art do more?

The Bad Man

PERHAPS the most thoroughly solid and satisfactory performance now on the New York stage is Porter Emerson Browne's The Bad Man. Here we have that rare conjunction, the play and the man, for Holbrook Blinn seems to have been designed by nature to step into the striding boots of Pancho Lopez, the bad man who is so good. And here, too, we have real satire; an acute, penetrating, and rollicking diagnosis of the Mexican situation which is a refreshing contrast to the mawkish sentimentalism of our political figureheads. With a single set of adequate scenery and a forceful compression in the sequence of events, The Bad Man seems to have had most of its non-essentials boiled out, leaving a residue most peppery, and satisfactory.

And then, by way of contrast and refreshment, there is Mr. Efrem Zimbalist's delightful little opera, Honeydew, which threatens to reestablish the preeminence of the old Casino in this particular section of the dramatic garden. Truly, it is an enchanting entertainment, clear and clever, with the most soundly written book I have heard in years and a score written in an idiom which is at once jazzless and joyful. At the head of a very capable cast, Hal Forde and Etheline Terry sing, dance, and fool, with much elan.

The two scenes, laid in Pelham and Larchmont, are another consolation for suburbanites and should boost realestate violently in those vicinities. And, look to your waltzing, young men for— once Mr. Zimbalist's score reaches our orchestral music-racks—the one-steps and fox-trots will surely have to take a back seat. to

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now