Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Bridge Player Who "Always Wins"

Advancing the Theory That Luck and Boldness in Bidding Have Less to Do with It Than Intelligence

R. F. FOSTER

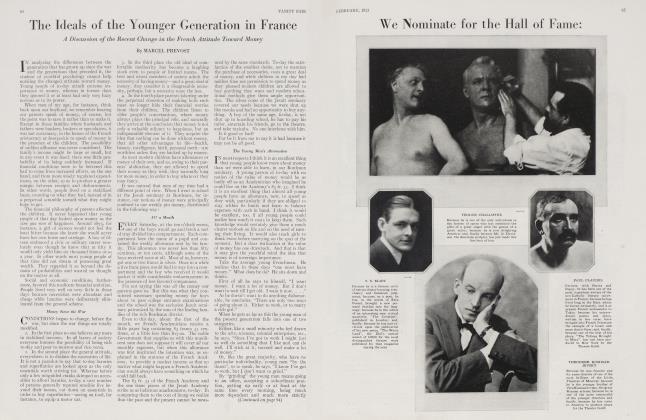

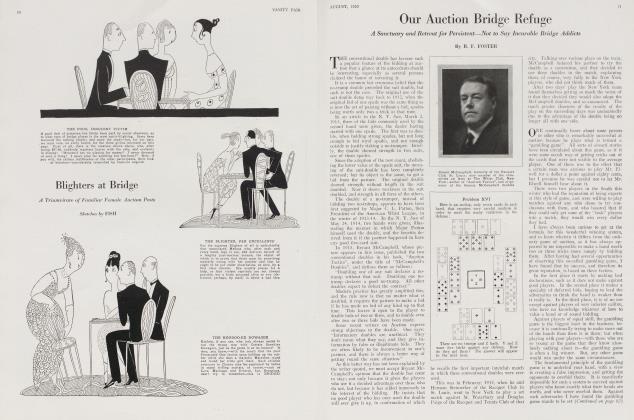

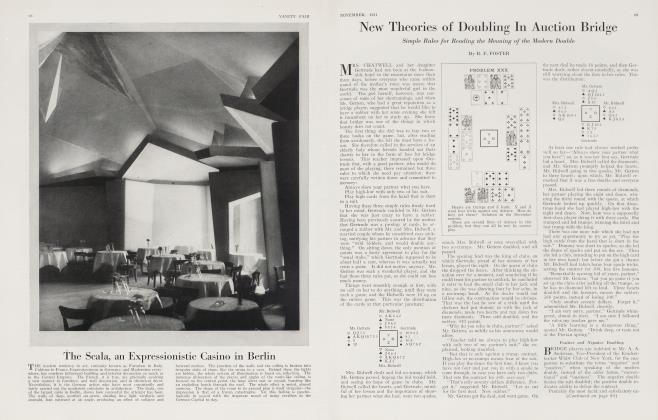

Hearts are trumps and Z leads. Y and Z want six tricks. How do they get them? Solution in the March number.

ONE of the many interesting questions in connection with the psychology of bridge is how to explain the fact that there are certain players who always win, or at least have the reputation of doing so, but who would never be considered as first-class players by an expert. Their bidding is often in direct violation of scientific principles and the laws of probability. They drop a trick or two almost every rubber they play. Yet they win all the time!

Everyone knows some such person in every club or bridge circle, and everyone seems to have an explanation of the phenomena. Some will tell you it is all luck; that so-and-so always holds wonderful cards. Others will say it cannot be this, because cards will equalize themselves in time. This is true; but in what space of lime?

Some persons are lucky or unlucky for one evening, and get it back the next. With it some runs one way for a week, with others for a month; with others for a year; with one or two in a million, it may continue, good or bad, for a lifetime.

The French have a saying that the most remarkable things are those that do not happen. If you toss a coin a thousand times and it does not come heads or tails at least ten times running, it is just as remarkable as if it came heads and tails alternately fifty times. The red has come up thirty-four times in succession at Monte Carlo. Mathematicians say it should do so about once in thirty years. The things we regard as most improbable are really to be expected in a long series of events, or among a very large number of individuals.

Transfer this probability to the individual card player, and take a thousand of them. There should be at least one of them whose luck would run ten times as long in one direction as the average. There are some individuals whose luck never changes. Mr. Charles Mossup, editor of the Westminster Papers told me he knew a whist player who had held phenomenal cards for at least fifteen years. This was a Mr. Hand, who kept the little money-exchange booth in front of Charing Cross Station, in London. I met him in 1891 and he told me that if he lost every rubber he played to the end of his life he would still be ahead of the game. Fifteen years later, when bridge was the game, he was still the greatest card holder in the club.

On the other hand, take James Petch Hewby, known as "Pembridge", the author of Whist or Bumble-puppy, acknowledged to be one of the best players in London. So persistent was his bad luck, year after year, that he had to join a club where the stakes were threepenny points, the lowest then known. He tells us of losing twenty-two rubbers in succession; laying off for two weeks, and then losing twelve more rubbers in a row. He once held two Yarboroughs in one rubber, the odds against which are three-and-a-quarter million to one.

The most popular explanation of the continued success of certain players, and the one usually offered by themselves, is that they are not afraid to bid their hands. In fact, they habitually overbid them. If this explanation is carefully examined, it amounts to this: They either make their opponents overbid in opposition, and set them; or they save games they otherwise would have lost had their opponents been equally courageous with their bidding, or they hit upon a fortunate combination of the hands by their apparently rash bidding, which a more scientific player would never have reached.

Now, there are no miracles in bridge, and simply bidding three will not make three odd, unless it was in the cards all the time. On the other hand, there are certain tricks that are worth a great deal more than their face value, and certain sure losses that are nevertheless gains. The trick that makes or sets a contract; that wins or saves a game; that secures a slam. It is better to be set 50, less 16 in honors, than to let them score 27 and 36.

The philosophy of forward bidding is usually set forth in the following formula. If you don't bid, you will never get the contract. If you don't get the contract you will never play the hand. If you don't play the hand, you will never win the game, and if you don't win the games you will never win the rubbers.

The ordinary game, including tricks and honors, is worth an equity of about 200 points. The rubber game, at least 300. As the odds are 3 to 1 that the winners of the first game will win the rubber, the forward bidder aims always to win that game, or to prevent his opponents from doing so. He is always willing to overcall his hand a trick or two. He may lose 50 or a 100 points, or may even come an occasional cropper that will cost him four or five hundred —but the other side do not win that game, and he is still in the running for the rubber.

The foundation of the successful player's game seems to be that if he plays the hand the other side cannot possibly win the game, but he may; and it must be admitted that he frequently does win games in the face of apparently impossible odds. The most striking feature that I have noticed about these forward bidders is that they very seldom double for penalties. Their objective seems to be to play the hand; not to defend it.

The popular explanation of the continued success of certain players seems to be about equally divided between their luck in holding cards, and boldness in bidding. Personally, I do not think either of these is the true solution of the problem, as will be seen presently. At the same time I have seen some remarkable examples of the results of bold bidding. Here is one.

The bold bidder dealt and passed; second hand three hearts, which the dealer overcalled with four diamonds. Four hearts was doubled by the dealer's partner. The dealer went to five diamonds, was doubled, and set one trick, 100 less 28; a net loss of 72. His opponents could have made four hearts doubled, which would have been worth about 260 points, counting a game as worth 125. At diamonds, the ace of hearts was trumped, and the king gave the declarer a spade discard.

Continued on page 92

Continued from page70

Personally, I do not believe that the success of those who are steady winners at bridge is due to their luck, or their bold bidding, to the extent that some persons would have us believe. I attribute it more to their intellectual superiority to those with whom they habitually play. They have better card sense; better judgment of human nature; a better idea of the psychology of the game. They may not be familiar with the niceties of calculating the strength of a hand for a bid; but they arc quick judges of the weaknesses of their opponents.

Take the leading players in our well known clubs, and they play with others in their own class, because they enjoy the game better. Winning is a secondary consideration. They are not playing bridge for a livelihood. The difference in skill between the best player in any club, and the poorest that will habitually cut into that table against him, is not more than 5 per cent; or one rubber in twenty.

But the players that have the reputation of being big winners in what might be called society bridge, seldom play twice with exactly the same set. They play bridge anywhere and everywhere, and their advantage is far beyond 5 per cent. Their courage in bidding, their judgment of opponents, enables them to take liberties with the game which they would not even attempt against the better class of club players.

My observation of these successful society players leads me to believe that the reason people say they arc lucky, or very bold bidders, is that they are not capable of understanding the psychological foundation upon which the successful game rests.

Answer to the January Problem

This was the distribution in Problem XLIY, which is one of the few contributions with which William B. Orr has favored us. The idea is both original and interesting.

Hearts are trumps and Z leads. Y and Z wants six tricks. This is how they get them.

Z leads his top club, upon which Y discards a diamond. Z follows with his smallest spade, the seven, which A wins. A can lead cither the trump or a diamond. If he leads the trump, Y wins the trick and Z discards the spade jack. Y then leads the winning diamond, and Z gets rid of the spade ace. Now all Y's small spades are good for tricks.

If A leads the diamond, instead of the trump, at the second trick, Y wins the trick, and leads the trump, giving Z the same two discards in spades, with the same result.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now