Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowPenalties That Some Players Pass Over

Showing That Few Good Auction Partners Know Much of the Rules

R. F. FOSTER

Mrs. TRUMPITT was from a town in the west, where they never played bridge for money. The limit, of their gambling, if such it might be called, was for the hostess, at the weekly meeting of the Culvert Club, to put up a dollar at each table for a prize. Mrs. Trumpitt's companion on the porch of a certain summer-resort hotel was a lady of large proportions, who talked glibly of playing for ten cents a point; but who usually refused to cut into a rubber if the stakes were more than a quarter a cent in real money. Mrs. Trumpitt speaking:

"I am looking forward to a lovely game this evening with Mr. Sharp. They say he knows everything about the game, as he belongs to The Bridge Club, and The Whist Club, and The Auction Club. They say he is a wonderful player. I think it's just lovely of him to play with us for such small stakes."

"Well, I wish you joy of the game. I played with him the other night, and I never want to again. Why, he is simply terrible."

"In what way?"

"Why he counts up more in penalties than he does in tricks. He's a regular bridge lawyer. When he got the choice of seats for the first game, he sat right down, and he made my partner choose his seat next, because he cut the third lowest card. Did you ever hear of such a thing? We always let the lady choose her seat, after the dealer gets his picked out. But that was nothing. He had a penalty for everything. I don't believe half of them were right. I was afraid to smile at my partner when we set them, for fear he would charge us 50 points for it."

Mrs. Trumpitt did not know what to say; but she thought it probable that the stout lady who played for ten cents a point did not know as much about the laws as she did about the stakes. The only discomfort she felt on cutting into the rubber with Mr. Sharp that evening was due to the sultry heat.

MRS. TRUMPITT won the cut for the choice of seats and cards for the first deal and took the chair nearest her, but finding the light not to her liking when she sat down, she changed one chair to the right. Her partner was not yet seated, as he was seating the other lady.

"I beg your pardon," remarked Mr. Sharp blandly, " but having once made your choice of seats you cannot change it. I am superstitious about such things." This was in the nature of an apology for his calling attention to the matter, as he saw she resented it.

"That is giving you the choice of seats," interposed her partner, turning on Mr. Sharp. "If you did not want those seats, you would not say anything. As you wanted them, you ask the lady to change."

"The laws give me that privilege as a penalty for Mrs. Trumpitt's changing her mind," was the calm rejoinder. The two men had met at the card table before.

Mrs. Trumpitt chose the red cards, partly because they matched her dress. Her partner told her the blue cards won every rubber that afternoon, and blue was his lucky color anyway, so she took the blue.

" I beg your pardon," hastily interposed Mr.

Sharp; "but having once made your choice of cards you cannot change it. You will oblige me by dealing with the red cards."

"There you go again," remonstrated her partner. "You are really making the choice of cards yourself, when you have no right to do so." This to Mr. Sharp.

"The laws give me that privilege, when my opponents make an error."

Mrs. Trumpitt took the red cards again, saying it really made no difference to her what cards she had, and began to shuffle them very dexterously, presenting them to Mr. Sharp to be cut.

"I beg your pardon," objected Mr. Sharp, pushing the cards from him, "but it is my partner's duty to shuffle those cards for you, as she sits on your left."

GETTING rather nettled at this continual fusillade of corrections, Mrs. Trumpitt handed over the pack to be shuffled, remarking at the same time that they never paid any attention to such little details at the Culvert Club.

"Now you can shuffle them," Mr. Sharp suggested.

Picking them up with the remark that she guessed they were shuffled enough, she began their distribution.

"I shall have to trouble you to let me cut those cards," Mr. Sharp interposed.

"Why your partner cut them after she shuffled them."

"It is not her cut."

The cards were gathered up again, and presented to be cut, after which they were dealt with a rapiditv that betrayed some annoyance. So rapidly in fact that at the end she found herself with only three when four were needed to complete the deal.

"Some of them may be stuck together," she remarked. "Please count them." Counting her own at the same time, she exclaimed, "There! I knew it. Two of mine are stuck together." Separating them she quickly completed the deal, and picked up her hand. Mr.

"IT has always been a question with me," he said, "as to whether or not that constitutes a misdeal. The law says the first card must be given to the player on the dealer's left, but it does not say the rest of the pack must be dealt one at a time. You must have dealt yourself two cards at one time, if two were stuck together."

"Well, what are you going to do about it?" demanded Mrs. Trumpitt's partner, getting impatient.

"As the last card now comes in its proper order to the dealer, I presume the laws have been complied with. I think I shall permit the deal to stand."

"Thanks, very much," the other man said. "Get the laws changed to suit your ideas better."

"What difference does it make?" demanded Mrs. Trumpitt. "They were only two little clubs anyway."

"That will cost you fifty points," retorted Mr. Sharp, putting the amount down in his honor column. "I thought you looked at the cards, but was not sure."

"Why, they are part of my hand. I should have seen them in a minute anyway. They were only two small clubs. I never heard of such a thing. Did you, partner?"

"I BELIEVE there is some rule about looking A at cards during the deal; but we never enforce it. We play bridge for amusement. As you say, you are going to see the cards in a minute, and it's a silly law anyway."

"I am not discussing the wisdom of the laws, but the facts," apologized Mr. Sharp. "What is the use of laws if you are not going to play the game according to them? And," turning to Mrs. Trumpitt, "I shall have to trouble you to place those two cards on the table, face up, as exposed, and liable to call."

"I did not see them," objected her partner. " I could not name them."

"That has nothing to do with it, my dear sir. Two small clubs were mentioned as in Mrs. Trumpitt's hand. That makes them exposed cards, as you mentioned them after the deal was complete."

Mrs. Trumpitt's only response was a shrug, as she laid down the four and deuce of clubs. This was the rest of the distribution, as actually dealt.

Picking up her cards hurriedly, Mrs. Trumpitt said, "No-trump"; but, glancing at the cards on the table, corrected herself. "I mean one spade. That was just a slip of the tongue, partner."

"You will pardon me, Mrs. Trumpitt; but you cannot change your original declaration."

(Continued on page 102)

(Continued from page 82)

"Yes, she can, too," interposed her partner. "The laws say you can change your hid if the next player has not said anything."

"If you will allow me," replied Mr. Sharp, "the laws do not say how we are to tell a slip of the tongue from a change of mind; but they do say very distinctly that if a player inadvertently says spade, heart, diamond, or club, meaning to name another of those, the mistake may be corrected. But it does not say one may change from a suit bid to no-trumps."

"They are rotten laws, anyway. Let it go at one spade."

Mr. Sharp's partner bid three diamonds whereat Mrs. Trumpitt's partner exclaimed, "Wow!" Mr. Sharp smiled, with apparent approval, at his partner, and Mrs. Trumpitt said, "Three spades."

"If you will allow me," remarked Mr. Sharp, laying down his cards, "your partner did not pass, and I have not declared myself. That is a bid out of turn, and I shall elect to cancel it."

"Then as you acknowledge I did not pass, I will bid three spades," replied Mrs. Trumpitt's partner.

"But you cannot bid at all, my dear sir, since your partner's out-of-turn bid was canceled. You are now also liable to the penalty for bidding when barred from doing so. I shall bid three hearts."

"That reopens the bidding for us. Your turn, Mrs. Trumpitt."

"Pardon me, but it does not. Had you kept quiet when I canceled your partner's bid, then Mrs. Trumpitt, who had received no improper information, could overcall me. But when a player bids while under obligation not to bid, that prevents cither of them from bidding, no matter what we do."

"I will bid four diamonds," from Mr. Sharp's partner, which he passed.

"Well, we shall never finish a rubber at this rate, partner," remarked Mrs. Trumpitt. " Please lead."

Her partner led the king of clubs. Mr. Sharp did not lay down his cards for the dummy. "You will pardon me again," he said, "but my partner has a right to prevent the lead of that suit, your partner having exposed a card of it after the deal was completed."

"You are dummy. You have no right to tell your partner what she can do."

"I have a right to call my partner's attention to an exposed card, and also to call attention to any right she may have under the laws."

"Don't let us argue any more about it," urged Mrs. Trumpitt. "Take back the club. I bid spades, not clubs."

"Now my partner may call a lead," interposed Mr. Sharp. "You refer to bidding which is closed." The declarer called for a trump, and the five was led. The nine won, and the ace was returned, Mrs. Trumpitt playing a small trump, without waiting for her partner or dummy.

"If you have no trumps, play your highest heart," demanded the declarer, turning to the man on her left.

"What for? Why should he play a heart?" asked Mrs. Trumpitt.

"If the fourth hand plays before the second, when the declarer leads, he may be called on to play the highest of any suit if he cannot follow suit to the card led," explained Mr. Sharp.

"I never heard of so many curious rules in my life," sighed Mrs. Trumpitt. "We don't play that way at the Culvert Club." While she was looking reproachingly at Mr. Sharp, her partner discarded the ace of hearts. The declarer led another trump, and Mrs. Trumpitt won it with the king. "Let me see. What did you discard on that last trick, partner?" reaching over and turning it up.

"That will cost you twenty-five points," remarked Mr. Sharp, crediting his honor score with the amount. "Looking at a trick turned down."

"Put down anything you like," protested Mrs. Trumpitt. "I like to play cards, instead of fussing about laws. I lead the ace of spades." A small club followed the ace of spades. The declarer won it, and led out all her trumps, making the rest of the tricks with the hearts and spades, but at the end, Mrs. Trumpitt's partner found he was a card short. On finding it on the floor, it turned out to be a small diamond.

"That makes five revokes," remarked the declarer, "I led trumps five times."

"I am sorry, partner," he apologized to Mrs. Trumpitt. "I always count my cards. "I don't remember the three of diamonds."

"The three of diamonds!" echoed Mrs. Trumpitt, "why I played that card to the first trick," turning up the trick indicated and showing a duplicate trey of diamonds in it. There was no four in the pack.

"Deal is void then," chuckled her partner. "We are in luck. Mr. Sharp has us down for about five hundred in penalties. But we could have made three spades."

"You cannot make anything with an imperfect pack," corrected Mr. Sharp.

"We have been playing nearly an hour for nothing," Mrs Trumpitt complained.

Answer to the October Problem

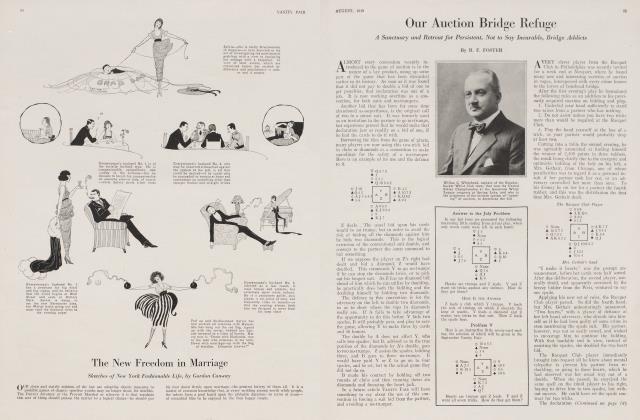

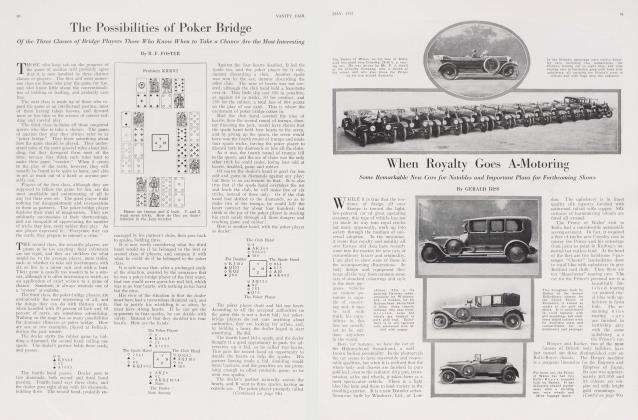

This was the distribution in Problem LII, which was a take-all proposition. As usual with such problems, the result depended on forcing discards.

Hearts are trumps and Z leads. Y and Z want all seven of these tricks. This is how they get them.

Z starts with the ace of spades, and follows with the ten, which A must cover with the jack. Y trumps the trick and leads the king of clubs. Z overtakes this with the ace and leads the trump, on which Y discards a small diamond. It is now up to B to do something.

If B lets go a diamond, all of Y's are good. If he sheds the spade, Z makes a trick with the seven. If he discards a club, Z makes a trick with the ten.

Several thought this problem could be solved by making those aces and kings separately; but they found this could not be done.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now