Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowLatter Day Helens

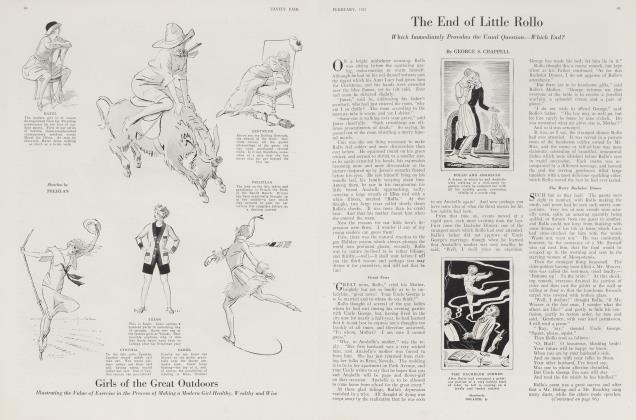

The Tenth of a Series of Impressions of Modern Feminine Types: Leda—a Vampire

W. L. GEORGE

LEDA spoke early, and it is significant of her temperament that she spoke with effect. For when her eyes first took in the world, and her tongue formulated a preoccupation, she did not say "Mummie" or "Pussy". In a firm tone she laid her hand upon the piano and said "Mine". Next day, taking pleasure in another object, she once more said: "Mine". She still does. Many events in the world are due to the act of God; the history of Leda is made up of acts of property, mental, physical, emotional. She acquires things as the flypaper acquires flies. The resemblance is acute; for Leda acquires all that she touches. In the words of Racine: "Elle eut du buvetier emporte les serviettes. Plutot que de rentrer au logis les mains nettes." She is capable of imposing upon all who approach her, men, women, old or young, a peculiar thrall. She does not merely dominate: she possesses. She flourishes as she devours, and those upon whom she preys tend to wither away; their vigour is sucked into Leda's system for her greater development and happiness.

One wonders what is Leda's secret, how it is that her sister Thalia sells Leda her new hat at a reduced price; why her mother who loves the silent peace of the country is compelled to hire boxes at the theatre in which Leda sits free of charge. It is a mystery. It is not Leda's beauty; it is not even the ugliness which terrifies; nor violence of word, nor effect of suasion. It is will. It is the power of desire, a sort of passionate flame that issues from Leda's heart, which all things burns away, obstacle, time . .. and the will of others. If she had been a man she would have been a Napoleon. Or the editor of a daily newspaper.

Leda and Her Husband

LEDA grew up as she began. She differed from Hermia in that she never sought to make herself the partner of a man, except in so far as the wolf is partner to the lamb. She never gave. She always took. Or gave only to receive back with interest. Thus the young men upon whom she cast her eyes were first drawn as the rabbit by the snake. Then, as they discovered the yawning jaws, they moved away, just in time, leaving behind merely a trail of flowers, candies, stalls at the theatre and a very little heart dust. But Leda married in the end: she wanted to. And she married very suitably a certain Patrocles who, after being sent down from his university, had failed as a curate. He had, however, a great deal of money, and Leda found him rather useful.

Patrocles lives a strange life. He is less even than Silvio Pellico, whose spirit was free while his body was in gaol. Patrocles is not so fortunate, for his spirit inhabits the narrow tenement that confines his body. Leda is improving his mind. Patrocles came to her as a normal man, loving light novels, fond of all cups that sadden but intoxicate, addicted to golf, able to laugh, and inclined to keep from the more serious side of his mind the deeds of the more frivolous one. Leda has changed all that. His novels have been presented to the Society for the Rescue of Washerwomen Who Have Seen Better Days. Now he can converse upon technology, ichthyology, and conchology. Eschatology is next on his list. Leda dislikes alcohol, so has converted him to lemonade. Leda is fond of loto, so Patrocles smites no more the rubber ball. Laughter, she says, does not suit his face, so he has learned gravity. When Leda buys a new frock she says to Patrocles: "Have you noticed my new frock?" Patrocles says: "Yes, dear." Sometimes Leda traps him with the help of an old frock; when exposed, Patrocles says: "Sorry, dear." He has no reason to complain, for his - life has been taken over by a superior power. He has no right to feel out of health, for Leda puts on his plasters, takes his temperature, boils his cup of arrowroot. (His skin suffers from the plasters; his temperature is always normal; arrowroot makes him sick, but what is a man to do?)

Once Patrocles was one of those dull men. A primrose by the river's brim, a yellow primrose was to him; Leda determined that it should be a great deal more. She has taught him to admire flowers, scenery and stars. He is not allowed to smoke his pipe under the stars. Such things are unseemly. Leda has induced him to sit upon the grass while she reads to him the sonnets of Shakespeare and selected passages from Ella Wheeler Wilcox. And from time 'to time she says: "Isn't it beautiful?" Then Patrocles says: "Yes, dear." From time to time Leda says: "Repeat the last line I read." Sometimes Patrocles remembers the last word. To remedy his ignorance, the passage is read over again and Patrocles shifts upon the damp grass, reflecting that he is rheumatic, and that if he says anything about it, later on Leda will dose him with salicylate of soda.

He admires that which Leda admires. It is best so, easiest so. To refuse to share her admiration leads to argument, conviction of error and defeat. Sometimes the cave-man ancestor of Patrocles asserts himself, and he says: "Please, dear ..." but Leda interrupts and says: "Wait until I've done." Patrocles has been waiting for eleven years.

A Universality of Interests

SOMETIMES Patrocles seeks solitude to meditate upon the good fortune that brought him such a wife. But he is never long allowed to meditate, for Leda says that daydreams fritter away his energy. Besides, he may not want to talk, but she does. Soon after their marriage he resigned from the Mausoleum, a club into which he had been admitted as a great favour. Now he belongs to the Cock and Hen into which Leda can' procure entry at all hours.

She often needs Patrocles, for theirs is a touching universality of interests. In this sense, that all which interests her interests him. (That which interests him is of course less important. Besides this has almost ceased to exist since his energy was taken up by her preoccupations.) Patrocles is busy in the mornings, for Leda reads to him all her private letters, especially such portions as bear witness to her variety of virtues. She tells him that Cloris, whom he has never seen, has just married Hercules, of whom he has never heard; his opinion is asked of Circe's new frock, and he hears the touching tale of how Circe's grandmother went on the stage. He has come to know these people intimately, for Leda goes with him to be by his side, in his direst boredom to be his guide. When Leda is photographed in the society papers, which frequently happens because she somehow inevitably gets into the way of the camera (in one case obliterating the Queen of Sparta) Patrocles has to examine the photograph. Is it a good likeness? Is it too good? Is it as good as last year's? Isn't her shantung jumper sweet? Which does he prefer: paradise or aigrettes? What! not know the difference between crepe georgette and crepe suzette? Fancy marrying such a man! Patrocles is getting better; he is learning; he can tell gabardine from Harris tweed.

Sometimes, when Patrocles sits at his desk, absorbed in conchology, and making a certain amount of progress, an exquisite interruption comes, as a butterfly settling upon a blossom. Away go the thoughts with such difficulty concentrated upon shells: it is Leda needing his attention and his time to tell him an interesting tale about the youngest of her aunts. As in all other things, Patrocles has a share in Leda's aunts. "Thy aunts shall be my aunts," whispered he on his wedding day. As whispered also Leda, for Patrocles has no aunts.

{Continued on page 86)

(Continued from page 29)

A Young Woman of the Sea

SOMETIMES Patrocles, akin to the tyrant of Samos, feels that life has given him too much, placed upon his shoulders a young woman of the sea, lovely, gay, gifted, but a little heavy. There comes upon him a need to commune with the shade he calls his self. He goes into his study and locks the door. But Leda has a skeleton key, and when she comes in she has tact enough to suggest that he must have locked the door by mistake. Patrocles is not entirely unhappy. He likes washing up dishes and having his views put right. Or if he does not like this, he feels it to be the wiser course to like what he has. Sometimes the weight of his companionship with the great tells upon him, but he knows that uneasy is the head that bears a crown. He bears the crown. He bears it very well. He proposed to Leda under the impression that he could support her; he has found that he must sustain her, be her shadow and maintain hers. Perhaps the irresponsible past that bred in him an irresponsibility almost ribald finds in his present life a chastening. He has found the usefulness of life that makes it dignified. His energy, his fortune, the graces of his daughters, the ambition of his sons, to what higher destiny could they be devoted, on what nobler altar could they be offered up than on Leda's, so that she may wax fat, grow sleek, enrich her lust for life with lusts less vivid?

Once Patrocles raised the anger of Leda. It was only once: during the honeymoon Patrocles and Leda made the popular agreement that Leda should have her way in minor issues and Patrocles in major issues; fortunately no major issues arose in the first eleven years. But something in the nature of a major issue occurred when Leda remarked that the day and night arose from the fact that the sun turned round the earth. Patrocles said: "I don't think so." The next two days were filled with denunciations. Patrocles knew nothing of astronomy; he was a brute; he did everything to cross her. If she'd only known! what would her sainted mother say if she were alive! Then more bitterly: Oh, had she but the wings of a dove ... ! At which Patrocles, with pardonable exasperation, replied that if she had the wings of a dove she could fly to the sun and see. Then Leda wept, and an immense sense of guilt fell over Patrocles as Leda repeated in broken tones that the sun turns round the earth. If she wills it, perhaps it does.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now