Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowLatter Day Helens

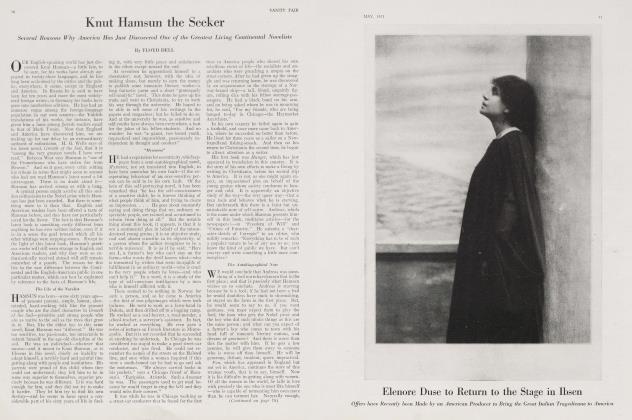

The First of a Series of Impressions of Modern Feminine Types: Electra, the Ideal Woman

W. L. GEORGE

Author of "The Second Blooming etc."

ELECTRA is pretty. Over the oval of her countenance the rose draws its petal, unaided by artifice, while her lips, thinner perhaps than a lover might desire, firmly close upon the certainties of her opinions. Her eyes are blue as the sea, and as cool; her fingers hardened by dutiful labours and trimmed to satisfy the order of hygiene rather than that of fashion. She dresses generally in 'blue serge, fit for the occupations of an active life, blue serge that marks none out for condolence or envy, blue serge that exhibits the symmetry of her lines, yet draws no man too emphatically away from the realisation of her severity. Blue serge. Electra wears blue serge.

At school she set up no canons of conduct; already she believed in liberty, provided it did not trammel her own; in equality, save with herself; in fraternity, except that she would be no man's sister. She had developed no theories as to the governance of the world, and was singular in this, youth being the time for generalisations. She had no time to consider the course of the life which enveloped her because her preoccupation with her own affairs served to isolate her from those of others.

So it was by beautiful example rather than by precept that Electra, in those days of inception, radiated influence as the beneficent sun radiates heat and light. Already she had pride of body, in that she washed with care and frequency, and always, used a symbolically hard tooth brush. Pride of mind also was Electra's, embodied not merely in the satisfaction of schoolmistresses and the bewildering of examiners, but in the acquisition of learning. Electra was a familiar of Tennyson and of Haeckel. Shelley she considered excessive until she discovered the date of his birth. He was then reprieved as a classic.

Few, if any, of the present generation of English novelists surpass Mr. George in his ability to present the current spectacle of English Society. He can plan a moving tale with the rest of his contemporaries: but he is not content to stop with the outward farce and drama of life. Without wandering into the way of the pamphleteer, he must go further and criticize his men and women with incisiveness and irony.

Mr. George has been especially successful in his analysis of women, both in his novels and his book of essays, "The Intelligence of Women". In the present series he has painted recognizable likenesses of twelve modern types; then he has, as it were, conducted us through his own gallery, explaining as a satirist the characteristics of each, their beauty and their ironies, their insistent virtues and diverting vices.

Electra and First Love

BEFORE she left the vestibule of school forthat other vestibule deceptively called life, she had been loved. A junior maiden wore a strand of Electra's hair in a locket, bought her flowers, cream buns and birthday books; a contemporary revealed to Electra the agonies of a soul wavering between two worlds. Miss Pink, the headmistress, inscribed on her last report, in the column entitled: "Remarks", the remark: "No Remarks." As this had never happened before, it was construed as implying emotion. Electra borrowed Miss Pink's motor-car to take her home, while other girls went to the station crowded in a char-a-bancs.

Then she forgot Miss Pink. Indeed, she had in her mind other preoccupations, being launched upon a world as to the acceptance of which she did not waver.

Electra was a success. She was proficient in dancing, golf and charity. She did not swear, but was not shocked if others swore. At tennis no member of her club could give or take from her fifteen. Her blouses were never cut so high as to recall a distant fashion, nor so low as to shame her evening frocks. On Sundays she always went to church, but only once. She read the novels of the day, but let it be known that she balanced with essays and political economy their inevitable frivolity. She went to the theatre, but did not consider that the drama was in decay. She had not yet developed into complete certainty of view; she was notable rather for crouching between two burdens. For love did not at once brush her with his rosy wing and mute her girlishness into womanhood.

Love did not touch her until she was twentyone. Then, in the labyrinthine dance, love held her in a mighty grasp. His name was Cleon; fervour filled his blue eyes, and a rusty glow lay upon his chestnut hair. "Heir of Lord Cleon, of Castle Cleon," thought Electra, "it would be very nice. Lady Cleon! Sables mullioned with argent couchant would make a charming coat-of-arms on blue notepaper."

For Cleon's sake Electra broke her rules and was seen alone with him at a matinee. When Cleon remarked that cold-cream never spoiled a kiss, Electra set aside her principles and bought a stick of lip-salve. But the night appointed for the exchange of their vows was preceded by a conversation with Electra's aunt, who wanted to know why her niece committed herself with Cleon, the humble scribe of a company whose servants went out to sea in ships. "You babble", said Electra. "Is he not the heir of Lord Cleon, of Castle Cleon?" "Of a Castle in Spain", replied the aunt rudely. "He is the youngest of the four sons of the youngest of nine brothers, my poor child!" When Cleon appeared with his yows there was none to barter with him.

For a while the world looked awkwardly to Electra. She went into the country, where the vicar was married and the curate nothing more than an occasion for folly, where thick boots made slim ankles merely wasteful, and where jokes that had once been funny did not have the decency to retire. For a moment Electra was weak: she thought of going on the stage. But the clarity of mind that distinguishes the great brought her back to town, where her friend Clytie soon confided to her that she was now promised to Daphnis, whom very soon she hoped to wed.

Daphnis and Cleon

ELECTRA congratulated Clytie with a good heart; her kindness led Clytie to confide that Daphnis, to prove his great wealth, was buying a diamond from the Inca of Brazil to make her an engagement ring: the jewellers had no diamond large enough for him. And Electra rejoiced with her, but thought: "My lot is hard, yet may be softened. Cleon was poor; thus it is manifest that he was not indicated by the theory of natural selection to be the father of my children. Daphnis is not in such a case. Alas, poor Daphnis! Clytie will not make him as happy as he deserves. She is unsuitable, and Daphnis should know it." When Daphnis knew, he was grateful to Electra. She felt that the theory of natural selection might harbour inscrutable designs, yet never erred in the end. So it came about that Electra married Daphnis.

She loves Daphnis, honours and obeys him.

Thus she pledged herself on her wedding day; she keeps its anniversary, not at the call of sentiment, but in the praiseworthy desire to record the course of righteousness. Indeed she loves Daphnis; shepherded by the latest manuals for the married she has shown him what passion may be concealed in purity, what purity in passion, what innocence in ignorance, what ignorance in innocence, until he has ceased to know which is which. Their affection is dynamic and subliminal, kinetic and tinged with universality. It is the most modem of passions. Electra, crowned with the roses of rapture and the myrtle of learning, remains a Good Influence. Daphnis does not slumber after dining, but furnishes his mind with the help of the more expensive reviews, the verse of Miss Amy Lowell and the revelations of Professor Freud. Mutt he knows not, nor Jeff. But the furrow he ploughs is not barren, for Daphnis is loved. Often, to reward an original remark, a profitable deal, or a fortunate neck-tie, Electra confers a kiss upon the Daphnis whom she loves.

And Electra honours him. She knows that he is the noblest, the most brilliant of men, that his opinion turns the scale upon which it weighs. How should it be otherwise? Does not his nobility originate from her precept, his wit from his memory of her conversation, his view from her dictum? How could she not honour one who was himself only till she came? Likewise she obeys him, for his orders embody only her desires. Aware of the fugitive nature of his impulses, she strives to implant in him only such wishes as are also hers. She knows, if not what she wants, then what he should want. New casting from an ancient mould, Electra brings up Daphnis to be loved, honoured and obeyed.

Once she was tempted, by an explorer. He wore a large black beard. Electra wondered what hid behind the beard. But he wished her to flee with him to Labrador, while Electra preferred Yucatan. This difference of opinion saved Electra; she chose virtue. Some say virtue's name is vanity.

As a mother Electra is the first proof of the future. Before the birth of her children she had practised maternity by correspondence course. Her descendants were bom experimentally, passed from Froebel to Montessori; then all had measles in turn. All were fed on Kalosoph, a synthetic food destined to develop together the aesthetic sense and phosphorus in the bones. All learned to walk eurythmically under Mr. Dalcroze. The attainment of beauty being the justification of life, every day for an hour beauty-drill was instituted; the girls contemplated Venus de Milo, the boys Apollo-. It proved a grief to Electra that her children secretly attempted to exchange life-classes. It was this caused her to have them psychoanalysed, which process revealed in all of them their father's worst sides. The unconscious realm of Daphnis had resisted suppression by Electra, but psycho-analysis, by exposing it, soon enabled her to suppress even that.

And now, in the footsteps of Mrs. Humphrey Ward, Electra treads the pleasant promenade called life, that unites two eternities. She is accompanied by a husband happy in the possession of one who is more than rubies. He has closed his ears to the song of the syrens that are various as their swelling throats. To the tune of her domestic harp, Electra sings to him the conjugal melody. She sings it well, for it is always the same.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now