Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Ethnology of Art

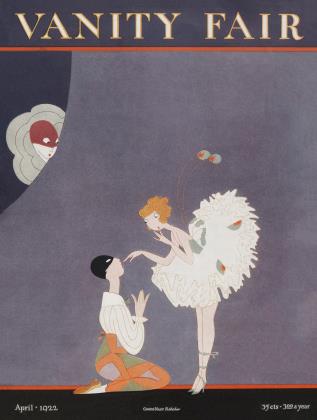

The Mating of One Aesthetic Line With Another Produces Some Remarkable Hybrids

GEORGE S. CHAPPELL

THE favourite habit of critics, that of speaking of one art in terms of another, is so ancient a trick that it would not deserve passing mention, were it not that what was once a mere literary device has today become an established fact. We used to gape admiringly at the high-brow set, led by Mr. Huneker, who delighted to speak of "the vivid red of an arpeggio," or "the rugged outlines of a contrapuntal motif." These mingled references and descriptions of vocal or instrumental melody in terms of graphic art were and still are de rigueur in the customary technique of criticism.

But the new phase of actual accomplishment is enormously more interesting. It all bears out another classic theory that art really precedes life instead of emanating from it as is so often supposed, for we see today the arts, which have been so freely shaken together to create the jargon of the professional critic, actually fusing and joining in the most extraordinary combinations. The movement is exciting, interesting, full of great possibilities and not unproductive of certain alarms. What are we doing? Where are we going? These are the two questions we should ask ourselves.

What We Are Doing

FIRST, as to what has already been accomplished. Well, it is as I have said, a great step forward. Let us consider a recent and very tangible illustration in the clavilux. We have always recognized the close affiliation between tone and colour. Vague fumbling attempts to reproduce colour by sound have been made for many years. But it was largely hypnotic. I say this was hypnotic, because I did a little psychological experimenting myself along these lines. In private life, I am quite a mean pianist and one of my parlour stunts was to play colours to an audience which couldn't escape. "Red"—I would announce,

ripping off a tremendous chord with about onehalf of one percent black notes in it. "Blue!" —a perfect C-major effect without any frills. "Lemon-yellow"—a sour little creature in the upper half of the key-board with a twiddling of the little finger. These used to go over big, considering that most of the audience were relatives. At my first performance the room was filled with murmured remarks as "Wonderful", "Interesting" and the like.

Then I foolishly tried saying "Red!" in an impressive voice and playing the chord I had previously used for blue. It went just as well as ever; no better, but fully as well. Of course I didn't tell on myself. In fact, I think I should have kept on repeating the performance indefinitely, had not my Uncle Theophilus said acidly that he couldn't hear red, but that he certainly would see it if I did that stunt again. So I say, the old way depended largely upon the hypnosis, produced by the statement of the performer, that such and such a combination of notes was green or purple or, if one wishes to play fashionable colours, fuchsia or taupe. There was no actual production of colours by musical mechanism. It remained for the clavilux to accomplish this.

When I first heard of the clavilux, I thought it was a medical term referring to one of the important bones of the human skeleton. I even made a bet on it, so sure was I that I remembered the wording of an old advertisement that a certain bicycle saddle was the most comfortable in the world because it rested firmly on the bones of the clavilux.

I was in error as I afterwards learned when I saw my first concert by the clavilux. It was a thrilling sensation. Here, at last, I realized that life had leaped into the realm of imagination, that music had, indeed, married painting. The fruit of their union was a large black box, six by three by three, which a reference to my diary tells me would hold approximately one and one-half tons of coal (gross) or two and one-half as sold by the local dealers, but which really contained a most amazing assortment of plain and fancy shades of colour, which were released when the soloist touched the keyboard in front of him. The first number on the programme was a brilliant little morceau called Danse Faune, which was gay and spring-like without ever becoming bilious.

I could not help thinking of Wordsworth's lovely daffodils and his immortal couplet "Ten thousand saw I at a glance, Nodding their heads in sprightly dance," and that set me to thinking of how I had sent a dozen to a young lady which had set me back three dollars, so that at that rate Wordsworth had seen $2,499 worth of daffodils at one whack. I wondered if he counted them or just guessed. He states so positively that he saw ten thousand, and yet since I heard about that fling of his in Paris I've not had quite the same faith I used to have. Into these pleasant paths I was led by the Danse Faune.

Then the soloist crashed into a colour performance of the Star Spangled Banner, magnificently played in red, white and blue but strangely reminiscent of the later opuses of G. Cohan. The clavilux is undoubtedly at its best in modern compositions written especially for its peculiar capabilities. Two fascinating novelties closed the evening, An Evening in a Boudoir arranged for three pinks and a lavender, and the exquisitely pastoral Scenes in Derby, Connecticut, in the key of dark-brown. All hail the clavilux, I say. I am delighted that it is not a human bone.

Other Arts

DANCING has always been handmaiden to the other arts. But here again we see how our restive moderns have not been content with merely talking about the matter, but have actually been and gone and done it. Mr. Ted Shawn, who was at one time half of the famous Denishawn atelier, has boldly applied his terpsichorean abilities to the expression of the great ritualistic forms of religion. He dances a complete service, Ted does, think of that! Everything—Invocation, Creed, Sermon and Doxology. One of the prettiest numbers in the bill is the Collection, with its accompaniment of small change dropping in the plate. The sermon bit, too, is splendid, for, governed by the law of physical reaction, it is mercifully short. This idea, I think, should be extended to other pulpits. If some of our stout clergy had to dance their sermons, their physical fitness would be tremendously improved. I should love to see John Roach Straton dance!

In other lines too, the Dance is carrying on. I recently attended a matinee performance at which one of our loveliest dancers performed to an accompaniment of verse, written for the occasion by two of our boy-poets. It was a fascinating affair. Inspired by the tripping accompaniment the dancer was a very thistledown of lightness;—so was the verse, which was practically lighter than air. It seemed to float gently to the ceiling of the auditorium and disappear. The general effect was charming, the total result—nothing.

The Art of the Aroma

THE realm of odour has by no means been neglected, though it lags somewhat behind its sisters in practical exploitation. However, I had the extreme good fortune to be present at one of the first of a series of Concerts d'Odeur —organized in Paris last year by that supreme smeller, M. Lucien Sentant. I shall never forget the picture, in the chastely decorated Salle Dupey, nor the exquisite programme which followed in which the art of France's first parfumiers was blended with the honest Gallic realism which did not hesitate to introduce the nasal echoes of garlic, fish and boiling glue whenever they were needed to complete the picture. The odours in this case were released from handsome urns, grouped in chorus formation on the stage, and wafted toward the audience by means of an ingenious arrangement of electric fans. In its lighter passages the effects were produced by choirs of atomizers in varying sizes, but, when the full force of the chorus was desired and the lids of all the urns were simultaneously removed, the effect was tremendous. A highly dramatic duet between a camembert and a roquefort was one of the hits of the evening and had to be repeated. On the whole, however, this phase of the sensory world still awaits its great genius who will express to a keenly smelling world, not only the great smell harmonies of pure olfactory art (performed on the aromatorium), but will also show its intimate relation with the other arts along the lines which have already been pursued by the Dance, etc. I can imagine nothing more exquisite than a ballet to the accompaniment of Quelques Fleurs or a tragic poem against a suggestive back-ground of grave-yard odours.

So much for what has been accomplished and it is indeed much. But we are only on the threshold.

Already those pioneers of modernism, les Six, of Paris are pointing the way to new strange fields of artistic explanation. Already we have had orchestral creations in which the instrumentation called for two typewriters and a washing-machine. Here is life following art with a vengeance. How pale and ancient seems old Richard Strauss with his imitative Sinfonia Domestica, with its squalling babies and smashing crockery. If we must have squalling babies in our concert halls let us by all means have them, but let them be real ones. The composer should furnish his own baby for the purposeoand it should be pricked or pinched at the exact wave of its parents' baton. I can imagine many a patient German studying the technique of a baby—the kinderflote—until he had acquired its complete mastery. Thus we may see every phase of domestic or office life invaded by this inventive, forward-moving spirit of combination which will make our stenographers and bookkeepers and scurrying clerks part of a mighty orchestra, which will in time, no doubt, write vast symphonies in which the voices of combination and progress will join and we will see towering buildings rise to an accompaniment of rollingmills, blast-furnaces, electric drills and riveting machines. A skyscraper will become an artistic performance:

Continued on page 106

Continued from page 47

Steel Solo, by the Bethlehem Company. Accompaniments by the Hedden Construction Co.

Certain forms of art are at a disadvantage. They do not blend readily. Sculpture, for instance, is by nature slow and laborious. An exhibition of granite chipping or marble carving, no matter how skilfully combined with other forms of aesthetic expression, would be dreary. The audience would walk out on it. Something could be done with clay modelling, in a swift, vivid creative act, combined with dancing and acrobatic stunts, juggling balls of clay, etc. So too with painting, the swifter mediums should be employed. I have tried this out in my own home and assisted by my cousin Wallace, have already performed several duets arranged for violin and water-colour.

In the main, care should be exercised to select for mating Art-forms which seem to have a natural fondness for each other. Their children will be healthier and more attractive. This is the basic theory of the new art-ethnology. We should avoid as far as possible the union of too widely dissimilar or opposed tendencies, leaving for the future, as we safely may, the invention of more and more strange combinations. I remember in my youth singing the refrain of a queer freakish song called The Wedding of the Lily and the Horse-shoe Crab. Such a union always seemed to me a strange, impossible thing,—but since I have seen what our artists are doing to art I am not so sure.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now