Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowAn Impression of Walter Hagen

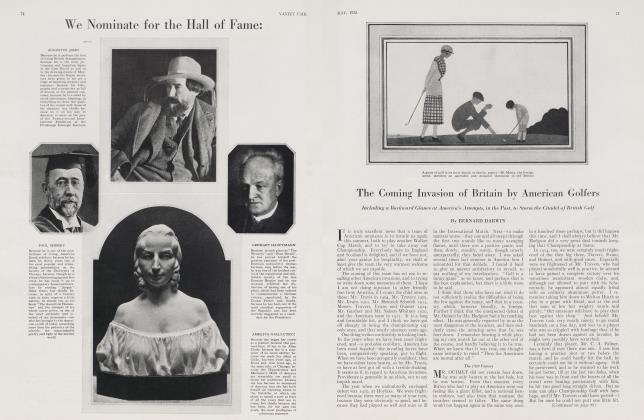

BERNARD DARWIN

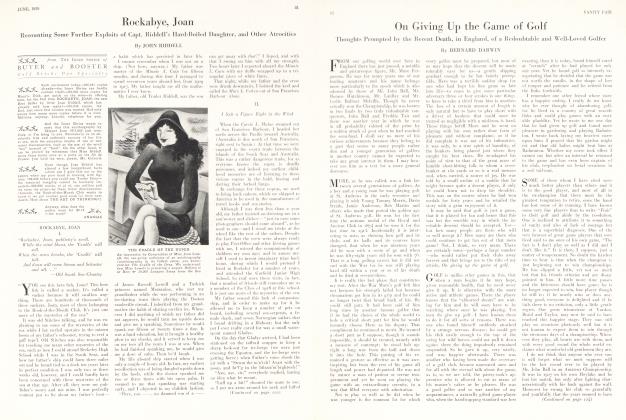

A Well-Known English Golfer's Portrait of the Present Open Champion of Great Britain

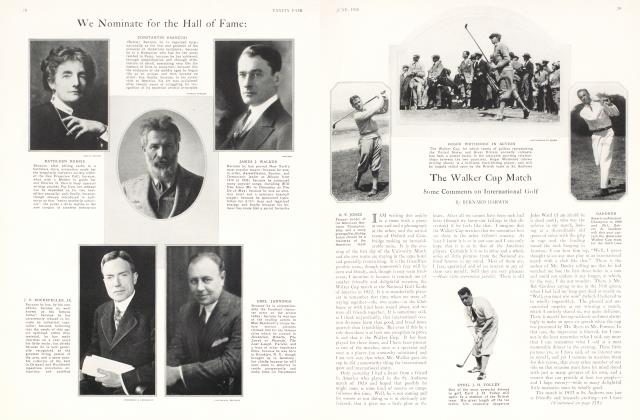

WHEN the Editor of VANITY FAIR asked me in advance, to write an article about our open champion for 1922, I hoped, as a patriotic British golfer, that I should be writing about a British champion, but my mind misgave me that I should be writing about an American one. When I got to Sandwich and watched Hagen and Barnes and Hutchison playing in the qualifying competition I had very little doubt about it, for their golf on those first preliminary days was as the writing on the wall.

And now that I am actually setting about my task, the first thing I must say, without the very smallest reservation, is, that your men played better than ours, and that beyond all doubt Hagen was the right man to win.

There are always "if's and an's" about golf competitions. Barnes might have won if he had not made a bad start in the third round, or could just have holed some very holable putts in that last wonderful spurt of his. The same thing is true of Duncan. Hutchison might have won but for a disastrous and rather unlucky seven at the 4th hole in his last round. That amazing veteran, Taylor, might—nay, I really do believe he would have won—if he could have taken one single stroke less at one single hole, namely a five instead of a six at the ninth in the third round, after he had set us all cheering, laughing and half crying with delight by holing the first eight holes in twenty-eight shots.

But Hagen had his "if's" too—we must not forget that—and right away through the tournament he always looked like a winner. He seemed to have just the best of the others by a subtle something. Was it a little more strength, or concentration, or confidence? I cannot put a name to it, but whatever it was, it impressed us all in the same way. From the beginning nearly everybody said "You'll see—Hagen will win in the end" and so he did.

Just after he had finished his last round, beaten Jock Hutchison by two shots and set, as it seemed, an impossible pace for the rest of the field with a total of 300, I heard Hagen say "I do love to fight when I know I've got to." This was not, I think, merely a piece of happy exuberance, coming from the relaxation of a great strain or from the enjoyment of the first cigar he had allowed himself for a week. He really meant it, and more almost than any golfer I ever saw he does rejoice in the battle for its own sake.

Hagen and Hutchison

BOTH Barnes and Hutchison are fine fighters. They appear to be more light-hearted than Hagen is, but they do not—unless my observation is all astray—relish the struggle quite so much. According to their different temperaments men will play golf in different ways. In scoring competitions ninety-nine out of a hundred will prefer not to know exactly "what they have got to beat": they have enough to think about in trying to do the best they can. The hundredth man likes to know, and he seems to me the man to back.

Hagen is one of these rarely constituted golfers. In the last round he started immediately behind Jock Hutchison, who led him by two strokes, and he deliberately kept himself informed of what Hutchison was doing. Thus when Hutchison had that disastrous seven at the fourth, Hagen knew that his deficit was wiped out. When they got to the turn, the deficit was back to a single stroke. When he reached the 12th and holed a fine putt for a three, the deficit had for the first time turned into a gain of one, and from that time forward he knew, hole by hole, that he was in front. No doubt in the world he played better for this knowledge, but most people would certainly have played worse.

Barnes is of the opposite school. He likes to concentrate entirely on what he is doing himself. Just as he was starting his third round Hutchison had come in with a brilliant 73 and a well meaning but indiscreet onlooker gave Barnes the news. Barnes very properly told him that he did not want to know, and asked him to be quiet. I am afraid the incident had a disconcerting effect on him, for he started that round very badly, and it was not till five holes were over that he seemed to regain his grip of himself. In the last round of all, when he was chasing Hagen in a really wonderful way, I believe he did not know exactly what he had to do—only that he had to do something very good indeed.

At the last hole of all it was perhaps a pity that he did not know. In fact he had a four to tie, and this last hole in a blustering cross wind was a very fine four indeed. His tee shot was perfect; his second with a brassie was pushed out and finished almost level with the hole, but some way from it in rough grass. There was very little room "to come and go on."

If Barnes was to get that four—a very, very difficult thing to do—he must risk taking six and cut his pitch very fine. If he only wanted a five there was no great difficulty, he could pitch well past the hole and come back to it with his approach putt.

I cannot help thinking that he believed, or half believed that a five would give him a tie. At any rate he pitched very safely, a long way past the hole, and Hagen who was looking on, breathed a sigh of relief. I hope I have not dwelt too long on this point, but you have heard long since of all the more obvious facts about this championship, and I hope this little piece of inner history, may be new. Moreover, it illustrates a difference between two very fine golfers.

Duncan's last mad rush to catch Hagen was a very wonderful thing. I call it "mad" advisedly, because Duncan played and periodically does play like one possessed. He just walks up to the ball and hits it, and as long as he is within reach of the hole, no matter what the club, he has an eminently holable putt for his next shot. To do a 69 round at Sandwich when you have a 68 to tie sounds remarkable enough in all conscience; yet I am told by levelheaded observers who saw the whole round that his score might very easily have been 65.

I had, on that day, been writing hard about Hagen and Barnes, and then, since I could hardly in decency send off my telegrams without seeing the end of Duncan, though I was without any real hope, I strolled out to meet him at the twelfth green. He had a fair crowd with him, so that it was clear that he was doing something out of the ordinary.

"What's he done?" I whispered to my neighbor on the green.

"Two under fours and - go in, you

brute!" he broke out as Duncan's putt for three just slipped over the very edge of the hole.

"He's had putts for threes all the way" he went on, "If he'd had Hagen to putt for him, Heaven only knows what he'd have done."

A Burst of Inspiration

ALLOWING a little for my friend's excitement, I believe Duncan might well have been several strokes better at this point, so accurate had been his approaching. As it was I reckoned that by no stretch of imagination could he do better than 70. I wandered disconsolately away, and only rejoined him at the long 14th. This time it was clear that from the spectators' demeanor something had happened. Duncan had got a three at the 13th, a very, very good 4 for other people, and for the first time the impossible seemed possible. He pitched to within 5 or 6 yards at the 14th, but the putt was short and wide. A tremendous iron shot left him a similar or rather shorter putt for a three at the 15th. He nearly holed it this time, but not quite. At the 16th, a very difficult one-shot hole in the teeth of the wind he laid a full spoon shot two yards from the hole. His partner went from one side of the green to the other and took five to hole out, while Duncan waited—and we all waited breathlessly. Then he rammed the ball straight into the hole. Now he had only to do the last two holes in the par figure to tie, but two harder "par" fours cannot be imagined. Each called for two wooden club shots, even for Duncan who can drive as far as anybody. He got the first four, not without a struggle, for he was short in two and had to get a nasty putt down. The last hole was something of an anti-climax. Two grand shots put him just off the edge of the green, and then at last that wonderful burst of inspiration broke down. He quite failed to hit his little pitch, and was a good six yards short. It was the death blow; he took a five and finished in 69.

(Continued on page 86)

(Continued from page 75)

I quoted my excitable friend, who said "If he had had Hagen to putt for him". It was a well deserved compliment to our new champion. Right through he putted beautifully, and was the most convincing putter in all that big field. He was always deliberate and yet never dawdled over his putts, and he always stood still and gave the hole a chance.

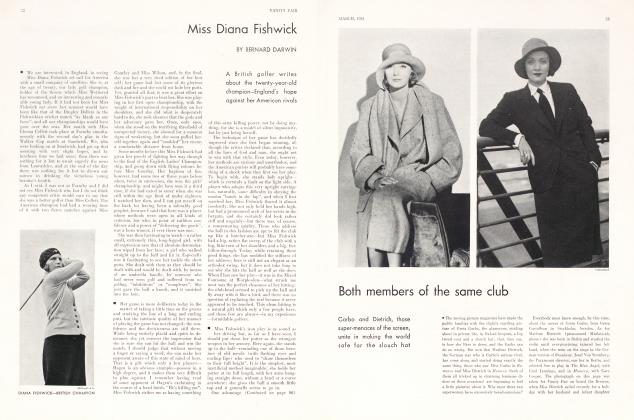

When your amateurs beat our team at Hoylake last year, there was a concensus of opinion that we had a good deal to learn in the matter of putting. After this, year's open championship we are more certain of it than ever. Somehow or other there has grown up a tradition over here that the very best of golfers must miss tiny putts. I don't know why it is; possibly because Braid and Vardon had a little weakness at times in that direction. At any rate we have come to accept it as an unalterable state of things to see our professionals play with mechanical brilliancy and precision up to the hole, and every now and again take three putts. Against Hagen this sort of thing will not do, and we have got to realize it.

The Progress of the Professional

I HAVE got a theory, whether sound or not, to account for the fact that professionals are far more human on the green than anywhere else. In their caddie days they never seem to possess a putter, so they do the best they can with a lofting iron. Watch a group of boys playing at their little improvised round of holes near the caddie shed, and you will see them all cutting the ball into the hole with much knuckling in of the right knee, and a forward lunge of their small bodies. When they grow up into professionals they have orthodox clubs to putt with, but they too often employ their boyish method. That method may do wonderful things when it does not matter, but it will not stand the test of a championship, when nerves are strung up. Then that man holes his putts who stands still and hits the ball truly, and the man who cuts or jabs or pokes or prods at his putts is lost. If one originally began to putt as a boy with a lofting iron (I speak feelingly on this point) one has got later on to put away childish things, if one can, and study putting with a proper club as an art to be learnt all over again.

I do not know whether your professionals have been luckier than ours and have owned proper putting clubs from their earliest years, but I am sure of one thing, that all your players have grasped the enormous importance of one or two cardinal points—such as standing still and hitting the ball smoothly—and have worked away till they have, as far as is humanly possible, mastered them. That is what our players have got to do now, and Hagen has given us much cause for gratitude by rubbing in so valuable a lesson.

I have been so very humble about our shortcomings that perhaps I may venture to point out one respect in which your champions might learn a little something from ours. Hagen—and Barnes too, though in a lesser degree— seems to have a rooted dislike to taking a wooden club through the green. He certainly can play great shots with that big driving iron of his, but a good many times he appeared first to underclub himself, and then to over-hit himself. He did not waste many shots in his four rounds and nearly all of those that I saw him waste, came from this exaggerated attachment to the heavy iron. He is so fine and accurate a wooden club player from the tee, that it is odd to see this antipathy to wood through the green.

I have no manner of doubt that he can play very fine brassie or spoon shots if he wants to, but he seems not to want to. Perhaps it is for the good of the world in general that he should have this one slightly vulnerable joint in his harness, for goodness knows he is formidable enough as it is—a great golfer who plays the game in every sense as it should be played.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now