Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Keystone the Builders Rejected

GILBERT SELDES

Slapstick Comedy of the Movies—Where the Genteel Tradition is Not—and Some of its Stars

LEST the year 1914 should be not otherwise distinguished in history, it may be recorded that it was then, or a year earlier, or a year later, that the turning point came in the history of the American moving picture. Critical the occasion was not; the old truths were already boresome and the new beauties, to judge by their present appearance, had not yet been born. Yet it was a moment when a good critic might have foretold the course of the moving picture for the next decade, for at that time was formed the Triangle of Fine Arts (D. W. Griffith), Kay bee (Thomas Ince), and Keystone (Mack Sennett). Mr. Griffith was already engaged in The Birth of a Nation, and, if I may borrow a phrase from the Shuberts, his personal supervision was often lacking; Mr. Ince presently began to meditate on the possibilities of joining the word "super" to the word "spectacle," thus creating the word "superspectacle"; Mr. Sennett—by a process of exclusion one arrives at Mr. Sennett always. He is the Keystone which the builders rejected. The best critic of the movies I know of, Mr. Bushnell Dimond, has recently called Mr. Sennett a Bourbon, in the sense of one who forgets nothing and learns less. I can only reply that Mr. Sennett had far less to learn than either of the two gentlemen with whom his fortunes were, in 1914, involved.

The Triangle Scheme

THE Triangle scheme, as it appeared to one who was content to be a spectator, leaving to less excitable minds the economics of the screen, was a good one. Each week there was to be released either a Fine Arts or an Ince picture; and each week, to go with these alternating masterpieces was to appear a Keystone comedy. So that those who were perpetually being caught in the rain, or missing the eleven o'clock train from Philadelphia to New York, always saw twice as many Keystone comedies as (a) Fine Arts or (b) Kaybee releases. From the recent acclaim of Mr. Chaplin as an artist because of The Kid, from the bright young reputations of men like Harold Lloyd and Buster Keaton, I should judge that most moving picture critics always caught the train and missed the shower. Except for lacking a few devices of lighting and a certain softness of tone, which soon developed into the dreadful gentility of the de Mille films, the Fine Arts and Ince pictures were in their time the best pictures produced; and the Keystone comedies were consistently and almost without exception better.

Regarding this phenomenon, Aristotle the Stagirite would probably have discovered the reason for it and the probable results. A hasty glance at The Poetics is sufficient to make one believe that Aristotle was aware of the importance of the medium; he would have seen at once that, while Mr. Griffith and Mr. Ince were both developing the technique of the moving picture, both were exploiting it largely with materials equally or better suited to another medium: the stage or the dime novel or whatever. Whereas Mr. Sennett was already at that time so enamored of his craft that he was doing with the instruments of the moving picture precisely those things which were best suited to it, and which could not be done without it.

I do not mean that nothing but slapstick comedy is proper to the cinema; I do mean that everything in slapstick is decidedly cinematographic, and that Mr. Sennett's developments were more capable of giving pleasure to the intelligent than those of either of his two fellowworkers. The highly logical, humanist critic of the films could have foreseen in 1914—that is without the eight years of trial and error which have intervened—that the one field in which the picture would most notably declare itself a failure would be that of the drama (Elinor Glyn-Cecil de Mille-Gilbert Parker, in short) and without a moment's hesitation would have put his finger on the two elements which, being theoretically sound, had a chance of practical success: the spectacle (including the spectacular melodrama) and the grotesque comedy. Omit as irrelevant the news reel, drawn comics, educational and travel films, and those clippings from the Literary Digest, which are at once the greatest trial and error of the screen. The rightness of the spectacle film is implicit in its name. And the great exception, The Cabinet of DrCaligari, the only film of high-fantasy I have ever seen, owes its success in large part to the skilfully concealed use of the materials and technique of the spectacle and of the comic film far more than it does to the dramatic quality of the story. Examples: the settings as variations of "scenery" or "location"; the chase over the roof-tops as psychological parallel to the Keystone cops; and, weakest moment of that superb picture, the double revelation, similar to Seven Keys to Baldpate, at the end, representing "drama."

I invoke Aristotle and imply Goethe and state generally this theoretical case for the rough comedy of the screen, because, after ten years in which it has never failed to give me pleasure and to redeem the solemn hours of the feature film, I see signs of degradation. The brutal stupidity of newspaper reviewers has left the picture comedy without criticism. Abuse and sly remarks about custard pies are not critically helpful. In the last twelve-month only one film made by Mr. Sennett has shown the quickening and fruitfulness of an idea: A Small Town Idol, in which, with the help of Mr. Ben Turpin's divinely crossed eyes, a burlesque of Messrs. Griffith, Ince and Lubitsch was successfully consummated. Bathing Beauties, unless Mr. Sennett is encouraged and subjected to rigorous criticism, will wash out the madness and the gigantic grotesquerie, the wild, monstrous sanity of the comic.

The Passing of the Comic Film

THE prettifying of the picture and the abominable pretentiousness of the manufacturers and exhibitors, especially in large cities, has much to do with the imperilled position of the comedy. In New York the Rialto Theatre alone seems to make a habit of Chaplin revivals and of putting its comic feature in the electric sign; the Capitol frequently announces a programme of seven or eight items without a comedy among them; you have to go to the simpler atmosphere of East 14th Street to find an old-fashioned movie house (who ever heard of an opera palace?) where Chaplin is always on view. Among those who would call themselves the elite, the comedy is below stairs, and the greatest mimic of our time has neither a theatre named after him, nor has any exhibitor had the sound business sense to devote a week to Chaplin alone. Tillie's Punctured Romance, in many ways a notable film for the career of Chaplin, was last billed in a Second Avenue converted auction room; Broadway would find it vulgar.

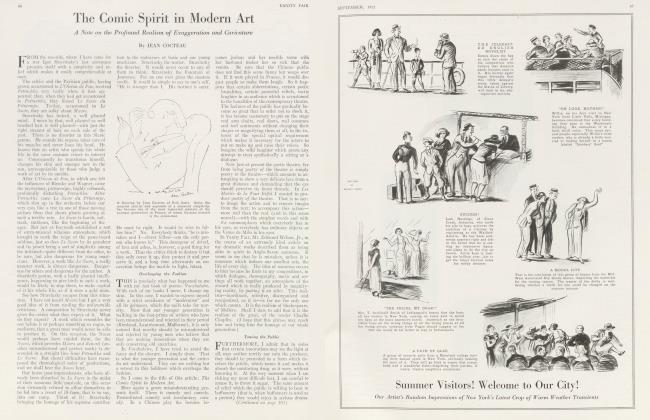

I confess to a certain impatience when people who have seen the Affairs of Anatole and the screen version of The Devil and Geraldine Farrar in Carmen, tell me that Mack Sennett is vulgar. They see the barber shop scene in a Hitchcock revue or Eddie Cantor in a dentist's chair, and they exclaim that moving picture comedians do nothing but throw custard pies. One wonders, with no great respect for humanity, what on earth moving picture comedians are expected to throw? I do not wish to make myself responsible for the millions of feet of stupidity and ugliness which have been released as comic films; my protest against the charge of vulgarity is on the ground that it is made by people incompetent to use the word and that it does not distinguish the slapstick comedy from most of the other manifestations of American humour—or of American anything.

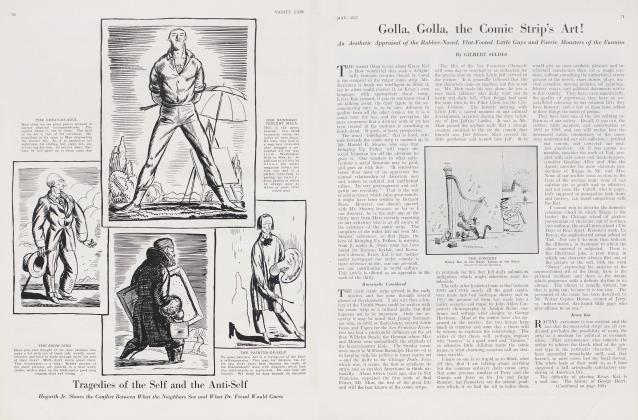

Elements of a Keystone Comedy

IN addition to Mr. Chaplin, there are nine or ten expert comedians whose work is always interesting and entertaining: Ben Turpin, Harold Lloyd, Hank Mann (if he remains as good as he was under Mr. Sennett), Buster Keaton, A1 St John, Mack Swain, Chester Conklin. Not counting Mr. Chaplin again, five of these have to my certain knowledge undergone the direction of Mr. Sennett; he, not they, remains the central figure. His ideal comedy is a fairly standardized article; regrettably, but the elements are sound. They include a simple, usually preposterous plot, the absurd essentials of a "serious" play; almost all the characters are grotesque and the protagonist is marked by peculiarities of his own: the Chaplin feet, the Hank Mann bang and sombre eyes, the Turpin squint; against the oddity and absurdity of the protagonist plays the serene idle beauty of a conventional girl (Edna Purviance, or Mabel Normand in the old days) or, on occasions, a comic in her own right like Louise Fazenda. Everything incongruous and inconsequent has its place in the unrolling of the events: love and masquerade and treachery; coincidence and disguise; heroism and knavishness; all are distorted, exaggerated, and—here the camera enters—all are presented at an impossible rate; the culmination is in the inevitable struggle and the conventional pursuit; into these latter enters trick photography: the immortal Keystone cops in a flivver mowing down hundreds of telegraph poles without abating their speed, locomotives running wild yet never destroying the cars they so miraculously send spinning before them, aeroplanes and submarines, everything capable of motion set into motion; and at the height of the revel, the true catastrophe, the solution of the drama, with the lovers united under the canopy of the smashed motors, or the gay feet of Mr. Chaplin gently twinkling down the irised street.

(Continued on page 92)

(Continued from page 55)

What all of these pictures have and what the serious film has not in any great degree is the perfect adaptation of the mechanism to the story. Analyse the common name and you find that what is wanted is movement and picture; analyse the camera and the projector and you find the secrets of pace and of distortion. Then go to the picture palace and spend one-third of your time reading the flamboyant titles of C. Gardner Sullivan and another third watching the contortions of a famous actress as she "registers," and you will see why the comic film is so vastly superior.

From Sennett's earliest day, the captions have been few and pithy. I recall in His Bread and Butter the opening title: "A Waiter's Farewell"—which for me sets the scene and gives me to understand that in the fantastic imagination of the Keystone comedy a waiter's farewell is immediately distinguished from any other person's farewell. (As played by Hank Mann it was.) In Bright Eyes the marriage of convenience is about to be made; the minister is about to pronounce the fatal words. In sweeps the bride's mother with these words: "Faint quick—lie's dead broke." Earlier in the same picture Mr. Turpin's diverted eyes have led him to dip his spoon into his fiancee's plate instead of his own. "I'm sorry," says he, "I had the wrong view." Captions are about one to every ten in the serious films and are usually not more than nine or ten words long. The close-up, a mechanical detail not actually essential to the picture, very seldom appears; virtually no comedians register, there is no senseless pantomime.

Everything is expressed by picture and movement; and from The Count (Chaplin) to The Paleface (Keaton), the retard and acceleration of pace has always been perfect. Seeing the former after a lapse of years, one can't help being surprised to realize how good it is, how unconsciously you are made aware of the approaching end of the play by the imperceptible hastening of the action until the last two or three minutes, with Charlie playing alternate pool and golf with the frosting of a cake, are a pure frenzy of activity. In the comic, too, the trick photography is suitably employed, although not even the comic has made sufficient use of slow-motion photography and of reversed projection.

Notable Slapstick Comedians

IT is hardly necessary to characterize the notable actors of the slapstick comedy; they are divided, roughly, into those who imitate Chaplin and those who do not, and all those I have mentioned so far do not. What all of them do, to a greater or less extent, is parody. The finest example of mock heroic was. probably Charlie's vision in The Bank; but Chester Conklin (or someone who much resembles him), in Bright Eyes, bundled himself up like Peary in the Arctic in order to fetch a ham from the ice-box, and came out to the adoring plaudits of the maid. In A Small Town Idol, Ben Turpin played, two years before it was written, virtually the whole of Merton of the Movies, piling into it a burlesque of the Western film and of the superspectacle such as I had never dreamed of seeing. The comic film began with the materials of the burlesque stage, I fancy; the materials, that is, which have been handed down in one tradition or another from the commedia dell 'arte: and it has never developed into the comedy of the intellect for one reason—that the comic masterpieces of the world have always been treated as material for the serious pictures. For myself, I would far rather trust Mr. Sennett to do me Sganarelle and Gargantua than any one else this side the water. Certainly I would not trust Mr. Griffith to do Aristophanes.

Within the limitation of what is, shall we say, physically funny, the comedians have done marvels. Mr. Chaplin is the greatest of all because he understands why one must never have irony without pity; he has piety and wit. Hank Mann, whom I place next for the work in His Bread and Butter and a few other pieces, translates the great childlike gravity of Chaplin into a frightened innocence, a serious endeavour to understand the world; he was trained, I have been told, as a tragic actor on the East Side of New York, and he seems always stricken by the cruelty and madness of a world in which he alone is logical and sane. If he steps unintentionally into a motor car instead of a street car, his willingness to pay his fare and let bygones be bygones represents his attitude towards life; his black bang almost meets his eyes and his eyes are mournful and pitiful; his gesture is slow and rounded; a few of the ends of the world have come upon him and the eyelids are a little weary; he is the Wandering Jew stirred into comic life by an unscrupulous fate.

His most notable opposite is Harold Lloyd, a man of no philosophy, the embodiment of American cheek and indefatigable energy; his movements are all direct, straight, the shortest distance between two points he will traverse impudently and persistently; there is no poetry in him, his whole utterance being epigrammatic, without overtone or image.

Chaplin and Others

TURPIN has the strength of the weak, like Chaplin, he disarms you and endears himself; unlike Chaplin, and to Turpin's advantage here, he knows how to be ridiculous. You see Chaplin pretending to be a man of the world and you see him as Chaplin sees him—the process of identification is complete and you feel only the pathos of the impending denunciation; Turpin, having only a talent for Chaplin's genius, lets you see him objectively, lets you see through him. Buster Keaton is the most difficult of the newcomers to be certain about; The Boat was a long, mechanical contrivance with hardly any humour; The Paleface had nearly everything which a comic needs, including certain movements en masse, certain crossings of lines of action which were quite perfect. His intense preoccupation—like Mann and Chaplin, unlike Lloyd and Turpin, he is always grave— and his hard sense of personality is excellent. Larry Semon is more ingenious than affecting to me; and behind him, but longo intervallo, begins the list of the misguided creatures who make the kind of slapstick comedies which most people think Sennett makes.

Seven years ago, in an imaginary conversation, I made Mr. David Wark Griffith announce that he would produce Helen of Troy, and I made him defend the Keystone Comedy. Mr. Griffith has not made Helen of Troy and the preeminent right to make it has passed from his hands. The Keystone Comedy (with its variations) needs still an authoritative defender and an authoritative critic. It is the one place where the genteel tradition does not operate, where fantasy is liberated, where imagination is riotous and healthy. In its economy and its precision it has two qualities of artistic presentation; it uses still everything that is commonest and simplest and nearest to hand, but there is no fault which is inherent in its nature, and its virtues are exceptional. It may require a revolution in our way of looking at the arts for us to appreciate slapstick comedy; having taken thought on how we now look at the arts, I propose that the revolution is not entirely undesirable.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now