Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

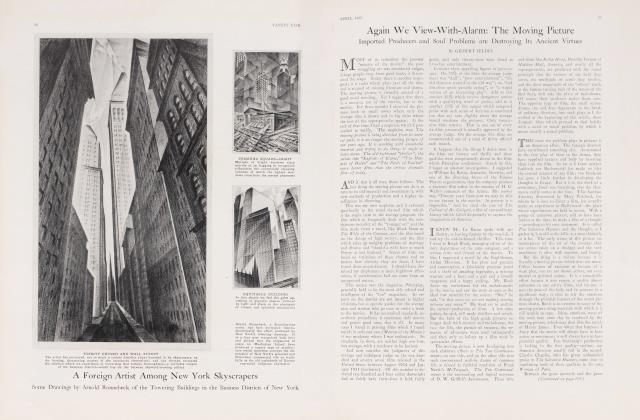

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowGolla, Golla, the Comic Strip's Art!

An Aesthetic Appraisal of the Rubber-Nosed, Flat-Footed Little Guys and Faerie Monsters of the Funnies

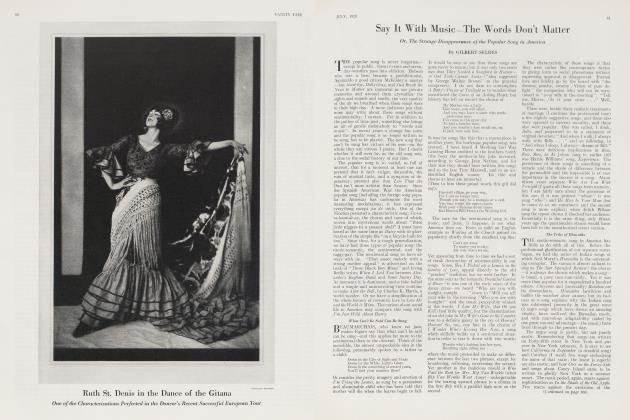

GILBERT SELDES

THE correct thing to say about Krazy Kat is How wonderful that such a delightfully fantastic creature should be found in the company of the vulgar comic strip. Mr. Herriman is much too intelligent to think it, but he alone could express it, in Krazy's own language, with appropriate floral irony. Krazy Kat (regard, if you do not know what I am talking about, the chief figure in the accompanying cut) is, to be sure, different in quality from all the other comics, but it is a comic none the less, and the perception, the mere awareness that a distinct work of art has been created in the medium is something to think about. It gives, at least, perspective.

The usual "intelligent," that is hard, attitude towards the comic strip is summed up by Mr. Harold E. Stearns who says that Bringing Up Father will repay the social historian for all the attention he gives it. One wonders in what satisfactions a social historian may be paid, and goes on with this: "It symbolizes better than most of us appreciate the normal relationship of American men and women to cultural and intellectual values. Its very grotesqueness and vulgarity are revealing." That is the sort of arid accuracy which ruins great minds; it might have been written by Bernard Shaw. However, one doesn't quarrel with Mr. Stearns because, as far as I can discover, he is the only one of the thirty men from Mars recently reporting on our activities who is at all aware of the existence of the comic strip. The compilers of the index left out even Mr. Stearns' references, so that Jiggs, the hero of Bringing Up Father, is missing from J; under K, where room has been found for Kansas, Kodak, and Korsakow's disease, Krazy Kat is not; neither under newspaper nor under comedy is there reference to this, our one art-work, our one contribution to world culture. This article is offered as an appendix to the work of the thirty.

Historically Considered

THE daily comic strip arrived in the early nineties and has gone through several phases of development. I am sure that a history of the United States could be written with the comic strip as a cultural guide, but that happens not to be important. Only for accuracy it may be noted that Jimmy Swinnerton who, in 1892 or thereabouts, created Little Bears and Tigers for the San Francisco Examiner has had a profounder influence on the art than Wilhelm Busch, the German whose Max und Moritz were undoubtedly the originals of the Katzenjammer Kids. The Sunday comic owes much to William Randolph Hearst—it is in keeping with his politics to foster native art —and the daily to the Chicago Daily News which was, it seems, the first to syndicate its strips and so enabled Americans to think nationally. About fifteen years ago, also in San Francisco, appeared the first work of Bud Fisher, Mr. Mutt, the first of the great hits and still the best known of the comic strips.

The files of the San Francisco Chronicle will some day be searched by an enthusiast for the precise date on which Little Jeff arrived in the picture. It is generally believed that the two characters came on together, but this is not so. Mr. Mutt made his way alone; he was a race track follower who daily went out to battle and daily fell; Clare Briggs had used the same idea in his Piker Clerk for the Chicago Tribune. The historic meeting with Little Jeff, a sacred moment in our cultural development, occurred during the days before one of Jim Jeffries' battles. It was as Mr. Mutt passed the asylum walls that a strange creature confided to the air the remark that himself was Jim Jeffries; Mutt rescued the little gentleman and named him Jeff. It is in gratitude for this that Jeff daily submits to indignities which might otherwise seem intolerable.

The only other historical note is that between 1910 and" 1916 nearly all the good comics were made into bad burlesque shows; and in 1922 the greatest of them was made into a ballet, scenario and music by John Alden Carpenter; choreography by Adolph Bolm; costumes and settings after designs by George Herriman. Most of the comics have also appeared in the movies; the two things have much in common and some day a thesis will be written to explicate the relationship. The writer of that thesis will, perhaps, explain why "movies" is a good word and "funnies," as offensive little children name the comic pages, is what charming essayists call an atrocious vocable.

I hope no one is so stupid as to think, after all this, that I am talking about anything but the common ordinary daily comic strip. Not some precious similars of Petey and the Gumps and Jerry on the Job and Judge Rummy, but themselves are the artistic products which, if we had the wit to notice them, would give us more aesthetic pleasure and intellectual satisfaction than (at a rough estimate, without consulting the authorities) ninety percent of the novels, short stories, plays, musical comedies, moving pictures, oil paintings, literary essays, and political documents native to this country. They have, even superficially, the quality of expertness; they have an unparalleled relevance to our common life; they have humour; and a few of them have added to these things the touch of genius.

They have been one of the few refining influences of our society. Recall, if you can, the clothes, table manners, and conversation of 1895 to 1905, and you will realize how the murmured satiric commentary of the comic strip underminded our self-sufficiency, pricked our conceit, and corrected our endless gaudierie. Or if you cannot remember, consider the work of Tad, peopled with cake-eaters and finale-hoppers, consider Gasoline Alley and Abie the Agent; consider the more elaborate productions of Briggs in Mr. and Mrs. None of our realists come so close to the facts of the average man; none of our satirists are so gentle and so effective; and not even Mr. Cabell, who is popularly supposed to monopolize both irony and fantasy, can stand comparison with the Kat.

I cannot stop to describe the domestic relations school in which Briggs is the leader; the Chicago school of plotless presentation of character, out of nowhere into nothing; the small-town school (The Days of Real Sport, Webster's work, Us Boys); the sophisticated urban school of Tad. Nor can I do more than indicate the difference in treatment to which the above material is subjected. There is the illustrated joke, a poor thing, in which one character always flies out of the picture at the end, with the word "Zowie" expressing his surprise at the unprecedented wit of the thing; there is the pictured incident; and there is the drama which progresses with a definite rhythm to its climax. The climax is usually violent, but that is going out, because it is too easy. The personnel of the comic has been described by Mr. Walter Cephas Hoban, creator of Jerry, as "rubber-nosed, flat-footed little guys who give offense to no one."

Krazy Kat

RACIAL caricature is non-existent and the fact that the successful strips are all syndicated precludes the possibility of using the strip as a medium for political or economic ideas. That circumstance also compels the artists to achieve the Greek ideal of the general type in the particular character. They have succeeded remarkably well, and they haven't, in most cases, lost the local flavour. The whole body of their work is, as I have suggested, a full, artistically satisfactory rendering of American life.

The difficulty of placing Krazy Kat is a real one. The history of George Herriman's other work throws a faint light upon this invincible creation. Long ago Mr. Herriman worked the vein of domestic comedy in The Family Upstairs; it wasn't, frankly, a success. To the realist reader the situations and the characters seemed always a little incredible; it was not that he failed to recognize himself, for one never does; he failed to derive from The Family Upstairs that superior feeling of recognizing his neighbours. The Dingbats, hapless wretches, had the same defect; Don Koyote and Sancho Pansy, and, just before the war, the great Baron Bean, were preparations for Mr. Herriman's best work. The first of these foreshadowed Krazy Kat and Ignatz Mouse; the second was, like Mutt, a character in the manner of Dickens. Like most of Herriman's favourite personages, he lived on the enchanted mesa, near the town of Yorba Linda, and he prosecuted a love affair with a lovely lady; he had a man-servant, and he was penniless. But his "Go, my paloma," to the dove which, since he hadn't the postage, was to carry his message of love, is immortal.

(Continued on page 108)

(Continued from page71)

Krazy and Ignatz entered, originally, as a footnote to The Family Upstairs. The thought of a friendship between a Kat and a Mouse was amusing; on their first appearance they played marbles and in the final picture the marble fell through a hole in the bottom line of the strip. An office boy named Willie was the first and Arthur Brisbane was the second, to recognize the strange virtues of Krazy Kat. Very slowly Herriman developed the theme to its present elaborate perfection.

The plot, in general, is that Krazy Kat (androgynous, but, according to his creator, willing to be either sex), is in love with Ignatz Mouse who is married and whose one object in life is to crown Krazy with a brick from Colin Kelly's brickyard. The fatuous Kat, for reasons presently to be explained, takes the brick to be a symbol of love and cannot therefore appreciate the efforts of Offiser Pupp to entrammel the activities of Ignatz Mouse. That is the framework of the action and it is important to know it, so that no confusion may arise; the brick of Ignatz has nothing on earth to do with the violence of other comic strips. Indeed it is often only the beginning, not the end of an action. Frequently it does not arrive. It is a symbol 1 I may say that it is the only symbol in modern art which I fully understand.

Mr. Carpenter has pointed out, in his brilliant little foreword to his ballet, that Krazy Kat is a combination of Parsifal and Don Quixote; Ignatz is Sancho Panza and Cesar Borgia; he loathes the sentimental excursions of Krazy, he interrupts with his brick the romantic excesses of his companion; he is hard and he Sees Things as They Are. But Mr. Herriman, who is a great ironist, understands pity, and often at the end it is the sentimentalist, the victim of acute Bovaryisme, who triumphs, for Krazy dies daily in full possession of his illusion. It is Ignatz, stupidly hurling his brick, unable to withstand the destiny which orders that he shall not know Krazy's mind, who fosters the illusion and keeps Krazy happy. Not always, for Herriman is no slave to his formula. The brick, one has gathered from an ancient Sunday strip in the Hearst papers, was, when the pyramids were building, a love letter—among those very Egyptians who held the Kat sacred. And sometimes the letter fails to arrive. Last week one beheld Krazy smoking an elegint Hawanna cigar and sighing for Ignatz; a smoke screen hid him from view when Ignatz passed and before the Mouse could turn back Krazy had given the cigar to Offiser Pupp and departed, saying, "Looking at 'Offissa Pupp' smoke himself up like a chimly is werra werra intrisking, but it is more wital that I find 'Ignatz.' " Wherefore Ignatz, considering the smoke screen a ruse, hurls his brick and blacking Offiser Pupp's eye is promptly chased. Up to that point you have the usual technique of the comic strip, as old as Shakespeare. But note the final picture of Krazy, beholding the chase, himself disconsolate and alone, muttering, "Ah, there him is—playing tag with 'Offissa Pupp'—just like the boom compenions wot they is!" Or again the irony plays about the silly pup who disguises himself to outwit Ignatz and directs Ignatz, also disguised, directly to Krazy. Here the brick arrives, but again Mr. Herriman goes on to a cosmic conclusion. For Krazy, laid out by the brick, sleeps and dreams of Ignatz while the pup walks by saying "Slumber sweetly, proud creature, slumber sweetly, for I have made this day safe for you." It is impossible to re-tell these pictures, and it is not for their high humour that I repeat the words. I am trying to give the impression of Herriman's incredible irony, of his understanding of the tragedy, the sancta simplicitas, the innocent loveliness in the heart of a creature more like Pan than any creation of our time.

The Dellikit Dormouse

ONE picture more, probably the masterpiece of them all; it will serve, too, as an example of Mr. Herriman's amazing language. Krazy beholds a dormouse, a little mouse with a huge door. It impresses him as being terrible that "a mice so small, so dellikit" should carry around a door so heavy with weight. (At this point their Odyssey begins; they use the door to cross a chasm.) "A door is so useless without a house is hitched to it." (It changes into a raft and they go down stream.) "It has no ikkinomikil value." (They dine off the door.) "It leeks the werra werra essentials of helpfilniss." (It shelters them from a hailstorm.) "Historically it is all wrong and misleading." (It fends the lightning.) "As a thing of beauty it fails in every rispeck." (It shelters them from the sun and while Krazy goes on to deliver a lecture: "You never see Mr. Steve Door, or Mr. Torra Door, or Mr. Kuspa Door doing it, do you?" and "Can you imagine my l'il friend Ignatz Mice boddering himself with a door?") his l'il friend Ignatz has appeared with the brick; unseen by Krazy he hurls it; it is intercepted by the door, rebounds, and strikes Ignatz down. Krazy continues his adwice until the dormouse sheers off, and then Krazy sits down to "concentrate his mind on Ignatz and wonda where he is at." Has Jurgen anything to equal that?

I have claimed for Mr. Herriman a great imagination and a fine ironic humour; at the risk of making all my claims seem ridiculous I must add that he is a fine artist. The first thing, after the mad innocence of Krazy, is to notice how Herriman's mind is forever preoccupied with the southwestern desert, the enchanted mesa. (Pronounce macey.) Adobe walls, cactus, strange growths, are the beginning; pure expressionism is the end. His landscape changes with each picture, always in fantasy. His strange unnerving distorted trees, his totally unlivable houses, his magic carpets, his faery foam, are items in a composition which is incredibly charged with unreality. Through them wanders Krazy, the most tender and the most foolish of creatures, a gentle monster of our new mythology.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now