Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

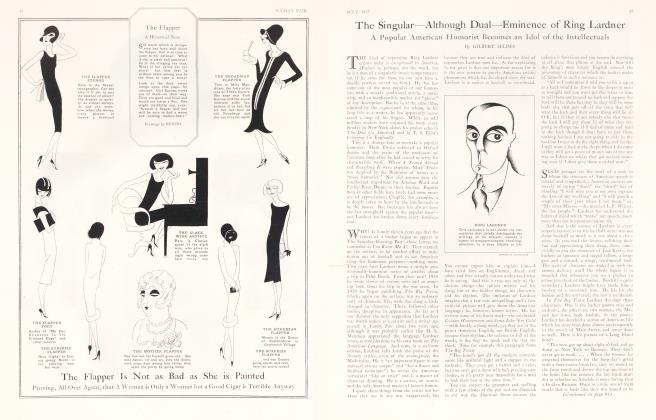

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowSome Premature Reviews of Our First Jazz Opera

Mr. Otto Kahn's Recent Invitation to American Composers Finally Meets With Success in 1935

GILBERT SELDES

THE news which spread, during the last days of 1924, that Mr. Otto Kahn had broken down the doors of the Metropolitan Opera House to make an entrance for jazz opera—that he had invited American composers to write an opera in the new musical technique —was received along Tin Pan Alley (which is on West 45th St. in New York City) with mingled emotions. Messrs. Paul Whiteman and Vincent Lopez, having actually played jazz concerts at Carnegie Hall and the Metropolitan, shook their heads and said, "Obviously".

The composers who wrote songs about Alabama in 1902, 1906, 1909, 1913, 1919, 1922, and the burlesques of songs about Alabama in the intervening years, said, "Yeah". It will be remembered that, at the end of that season forty box-holders at the Metropolitan sent a round robin to Signor Gatti-Casazza, praising him for the work he had done during the season, and asking that, as a special favour, the next season might begin with II Trovatore instead of Aida. They also humbly begged to be excused from attendance if, and when, a jazz opera was produced.

MR. GEORGE GERSHWIN, on hearing of Mr. Kahn's invitation, remarked to George White that this would be the last year he could collaborate with him on the Scandals, as he was working on a jazz opera for the Metropolitan, based on the life of William Ewart Gladstone. During the twelvemonth ending June 30, 1926, fourteen operatic scores plainly marked "jazz opera" were presented to the Metropolitan, most of which were found to be arrangements in 2/4 time of Madania Butterfly. By 1930 there were 450 jazz orchestras playing in New York (of which only 125 were directed by Paul Whiteman) and during the same year the first great American jazz opera was produced at the Metropolitan Opera House.

For those who were not present at the premiere we reprint portions of a review, published on the following day, and from a Sunday Times article published the next Sunday. It is of course impossible to recapture the feeling of exultation and of anger which suffused the breasts of music lovers at the time. In the Times-Tribune-Item, Mr. W. J._Gilderson, the music critic, wrote:

"Since the days (eheu fugaces!) when the Palais Royalists under that beaming Bourbon, Paul Whiteman, stormed the sanctuaries of Aeolian and Carnegie Halls,, the clamour has continued for such an opera as was produced last night. The opera Carlo Rossi is the result of such an agitation; an agitation, to be sure, more in the press than in the minds and hearts of the composers. It is, we are assured, a jazz opera. On its merits jazz, rather than opera, must stand or fall.

"The idea of using the story of the kidnapped Charlie Ross as a book, or plot, was a good one; and by a stroke of talent the kidnapper was identified as Jesse James. From this it soon became inevitable that the rescuer should be Buffalo Bill. This was well enough to start with, although it provided three principals in the male line and the balance of voices was not met by any balance of plot-interest in the bovver of beauty which provided the love themes. The American mythology is not rich in women; but we must admit that Dr. Mary Walker served the purpose rather well as the trouserwearing mother of Charlie Ross, and the secret wife of the bandit Giuseppe. For Guglielma da Buffo, nothing more adequate was discovered, in the way of love interest, than the Statue of Liberty; exposure to the weather, we must assume, has given her the basso-contralto voice ascribed to her in the score.

OPERA AND JAZZ

OMETIME ago a remark was incorrectly ascribed to Otto Kahn in the newspapers expressing a wish that a great American Opera might be written in the Jazz medium. Mr. Kahn did say on one occasion that he hoped for an opera typical of American atmosphere and temperament. On another occasion, in speaking to the Chamber of Commerce in Brooklyn on "The Advancing Tide of American Art", he offered a defense of Jazz in the following words: "A movement which in its rhythm and in other respects bears so obviously the American imprint, which has developed new instrumental colours and values, which has taken so firm a footing in our own country, aroused so much attention abroad and has been of such great interest to foreign musicians visiting here, must be taken seriously." That Mr. Kahn's son, at least, takes Jazz with the proper seriousness is attested by the fact that he is the Director, of an organization, The Roger Wolfe Orchestra, devoted exclusively to Jazz compositions.

In this article Mr. Seldes assumes that the American Jazz Opera has actually been produced and is reviewing it on the day after its presentation and, then, some years later, when it has become a classic, and, finally, a cumbersome obstruction to the young radicals of the day.

Meanwhile, the Theatre Guild has actually produced a new play, "Processional" (otherwise designated as "A Jazz Symphony of American Life" and "A Rhapsody in Red") in which the various threads of life as it is lived in a little American mining community, are woven together in a grotesquely vital whole, permeated by the harsh strains of a Jazz band to which, after' love, death, and comedy have stalked the boards, the various persons of the drama are, with characteristic American adaptability and optimism, left dancing.

Elsewhere in this issue Mr. Van Vechten has expressed his belief that in the work of a musician like Gershwin, Jazz may be exalted.

"So far, we hope, our temper has been in hand. We can even record without undue venom the fact that the choice of Ann Pennington (not so well disguised as Anna Pennantova) for the soprano solo dance and love making parts, was a proper one. The plot is neither better nor worse than that of II Trovatore , which it greatly resembles. But, regrettably, there was also music.

"Loud but not clear was the music to which these personages were supposed to sing; noisy and monotonous to the ear, knee-breaking and heel-scorching, every bar of it. To give the composer scope, Mr. Gatti-Casazza in the eightieth year of his direction of the Metropolitan was compelled to discharge twelve first violins, eight violas, and the whole choir of double basses and to replace these artists with saxophones of every range and quality. The manufacturers of nickel-plate-polish who seemed to compose the greater part of the audience were thrilled at the sight of the saxophones, but those who had ears heard not. Not music in any case.

"THE music of the street has no place in the classic halls of the Metropolitan. Opera, chicfcst glory of our artistic time, requires beauty, requires high emotion, even high intelligence. In the jazz opera we received only high notes on the trumpet and a sort of fierce sonority. It will not do. Nor have we any too much sympathy with the claim that this is an American opera. If we really want American opera we can always have Natoma, a vulgar burlesque of which, called Not-at-homa, was introduced in the Far West scenes of last night's production. American music is not the music of the darky and of the dance floor; it will always remain what all good music has been, a natural development from Bach, through Wagner and Verdi, to Puccini. All else is vanity."

It was on the following Sunday that Gilbert Taylor wrote, in the Herald-Sun-Globe-World, the following meditations:

"Mr. Kahn and Mr. Gatti-Casazza succeeded, yes. But what, exactly, did they succeed in? In attracting a large crowd of people to the Metropolitan who had never been there before? In getting first page headlines for the opera after its years of desuetude? In annoying the small group of true music lovers who staged a riot at the doors? In all this, of course. But in producing a jazz opera? I doubt it.

"It was an opera, all right. It was sung in Italian, which proves it. Everybody vocalized and nobody sang, which proved it again. Rosina Galli danced, and no opera is an opera unless she dances in it. But was it jazz? Not if Ted Lewis knows it. Not if Tin Pan Alley knows it. Not if the American people know what jazz is—or was. It was merely a sort of pale pink Puccini. It was jazz prettified and dulcified and genteelified out of existence.

"THOUSANDS of sound waves have run under violin bridges since we began to take jazz earnestly; and jazz has repaid us by taking us in dead earnest. It has lost its ancient impudence and divine mockery, its surprises and its fun. It is as respectable as the plush scats and dowagers before which it was played last Tuesday night. The Metropolitan might have opened its doors, but not on a subscription night, to jazz. (Oh, astute unfailing Gatti!) When the first American jazzer discovered that one saxophone could do the work of six violins (his name was Hickman, I believe) he started something. He reduced the overhead of good music. When the second jazzman discovered that you could play jazz without tin pans and accessories (his name was Whiteman or Riesenfeld or something like that) he turned what was a form of entertainment into a rival of the ancient symphony orchestras—rivalling them not in beauty but in dullness. In 1924 the attendance at a jazz concert was fresh and lively; it liked music. Today there are season ticket holders, regular subscription concerts, and the same air of vacuity which used to be the peculiar characteristic of the old-time concert hall. Jazz has been regularized.

Continned on page 94

Continued, from fage 42

"On the credit side there is this to be said: the material was fresh, the Buffalo Bill-Jesse James legend was freely handled, and the burlesque scene was gloriously funny. In this Miss Galli made way for a group of steppers, or hoofers as they should be called, who really knew how to dance. If they had cast Mri A1 Jolson for Jesse James and, instead of the prettypretty tune of his longing for home, had let him sing a Mammy song, the evening might have been saved. But it was lost in a welter of pseudoItalian pseudo-American vocalization."

And now we must skip a period of five years and read a later review of the same opera from the Times-TribuneGraphic for November 18, 1935 :

"The Metropolitan, this year, opened its season with Carlo Rossi— this being the first time that an American opera has been given the place of honour in the season's repertoire. It is too late now to revive the quarrels which the first production of this opera evoked. It has now won its place as one of the outstanding works of our time, and the other two jazz operas in the Metropolitan's repertoire, although not so notable historically, have proved that Mr. Kahn was a far-sighted and intelligent lover of music when, in 1924, he first proposed this interesting innovation.

"The opera certainly has dignity. In comparison with the vulgar music which now floods the streets, (the racking noises and musical brutalities of our musical comedies) Carlo Rossi proves itself decent and dignified."

Here we skip another five years and find in the World-DispatchNews during the year 1939-40 the following items published in the order given below:

"For ten years now the Metropolitan has been posing as a friend of American music and, whenever asked to prove it, the immortal Mr. Gatti has pointed to the production of Carlo Rossi, of Teodoro Teddy, of La Bella di Nuova York. Still in the bloom of youth, Mr. Gatti can cast back to the days of uproar and violence when, in 1930, the first jazz opera was produced. We are inclined to think that the memory of the occasion when—it is said—he received a broken leg and a slightly discoloured eye, deters him from doing his obvious duty.

"For, to any unprejudiced observer, it is clear that jazz is no longer the American national music. It has served its purpose, but it is now outmoded. It no longer corresponds to the pace of life in America. If Mr. Gatti really wants an American opera he knows, as well as anyone knows, where he can find it.

"Out of jazz grew razz—an unfortunate name, but a brilliant type of music in spite of its name. Razz, and razz alone expresses America. But, of course, the Metropolitan would not open its doors to razz. It is not general enough. ..."

Several months later:

"Mr. Otto Kahn has established a fund of $500,000 for the study of razz in our colleges. Mr. Kahn believes the time will come when a great American razz opera will be produced at the Metropolitan."

Toward the end of the season:

"The usual small crowd saw the usual performance of Carlo Rossi at the Metropolitan yesterday afternoon. It was the last performance of the season and many rumours were heard in the lobby that the opera would not be on the Metropolitan active list next year. A razz opera, II Presidente Calvino, has been accepted by the management for production next season. If this report is true, this will be the first time that a four act razz opera has been produced in America."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now