Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowDuse Once More

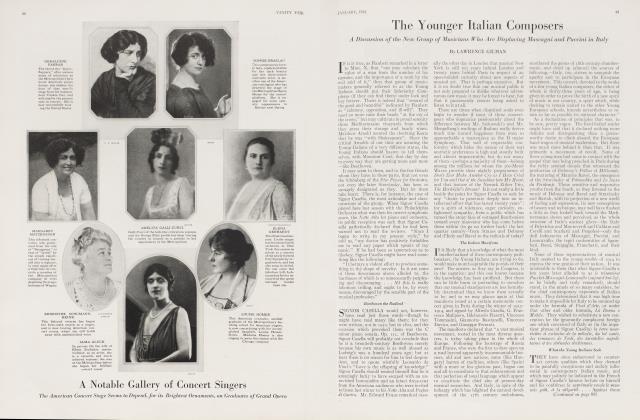

A Description of the Great Italian Actress on Her Reappearance After Fifteen Years

H. GRANVILLE-BARKER

I must be nearly twenty years since Duse last played in England; it is fifteen or A more, I am told, since she has appeared with any regularity in Italy. Now within the last few weeks she has produced a new play in Rome—a press failure; and she is scattering a handful of performances of her more accustomed work elsewhere.

When The Lady from the Sea was added to her repertory I am not sure. It is, past much dispute, the weakest of Ibsen's maturer plays, and I was sorry to have to renew my homage to a great actress through its medium. Had she chosen, though, to come back to the stage reciting a dozen nursery rhymes, no doubt the six or seven tiers of the Paganini Theatre at Genoa would still have been as crowded and the seat-profiteers as ravenous. One must not be churlish, however. There are many worse plays available, and, Duse apart, one would still find this well enough staged and acted; one really must learn, besides, not to go to the theater in search of sensation. Nor, where Duse is concerned, should this be such hard counsel, for it is a thing she never condescended to deal in. And if one felt like joining in the gods' impatient chorus, while the curtain's rising was delayed, of "E-le-a-nora! E-le-anora!", and if, while the first act ambled along, one thought less of the play than of the imminence of Ellida's appearance, that, again, was hardly her fault.

Duse To-day

WELL, twenty years have made such inconW siderable marks as they can. The black hair with flecks of gray is white hair now with flecks of black, the voice has not quite the penetrating power it had. There are other changes though, that need not be laid to time's account. Duse always did face her audience now with indifference, now with a slight air of disdain. It was as if she had had that couplet enunciating the gospel of artistic harlotry with "They who live to please must please to live" translated and stuck above her dressing table, and had taken oath that this should never at least apply to her.

It was certainly a prime article of her faith, that what she could not find in her study of the play she would not put in the performance; and if people came looking for a pretty virtuosity of charm—let them go elsewhere! Not a trick of the trade she did not know, as anyone could tell who watched her technique in the old stock exhibition parts like La Dame aux Camelias, and La Princesse Georges. To say that she had them all at her fingers' ends is an apt metaphor, in that she always seemed to be washing her hands of them. Having, rather disdainfully, given them as much of their due as the style of the part demanded, she then turned seriously, ruthlessly, to such an interpretation of the character as it interested her to achieve.

Retirement, and the freedom from any obligation to audience or dramatist, seems, one must own, to have deepened this disdain, to have extended it even to the character itself, even to have transformed it, as far as an applauding public is concerned, to something like disgust with the whole business.

I am suddenly driven to ask, indeed, whether acting is not after all a young person's job, whether the ability to abandon oneself generously and recklessly to vicarious emotions can survive the disillusions of maturity. Not that the number of human beings who ever do mentally and emotionally mature is so great that the application of such a doctrine would deplete the theater unduly. But Duse nowadays, it is evident, cannot quite yield herself. Never, surely, did any player of a part so prefer the part's interests to the player's. To watch her through the colloquy with Arnholm in the first act is to realise to the full this extraordinary self-denying power by which she brings, not only the part, but the whole play to a seemingly independent life. But when we come to the climax of the Stranger's appearance it must be owned that she is more inclined to demonstrate to us "This, or something like this, is the sort of thing that Ellida did," than impersonatively to do it.

And, looking back, one realises this to be the development and hardening of a tendency that was always apparent in her work. It is the defect of a great quality. As she foreswore the conjuring-trick style of acting (the equivalent to the yards of ribbon and the two white rabbits extracted from the empty hat) and would show us no more of a character than she could honestly make of it, so she would never pretend to surrender herself to its emotions when, for any reason, she could not. The power of mental identification with the character is apparently always at her command— and therefore at our service. But for the final touch—if she lacks the impulse to it, we must go without. She will not, for any thing, tell us an artistic lie. These are the ethics of artistry indeed, and who shall say that they are not wholly admirable? But an audience, accustomed to have its appetite for sensation ungrudgingly pandered to, is apt to chill somewhat at this demand upon its virtue. We bow down to Duse; who could olo otherwise? There are happy times when her playing is such a complete fulfilment of the obligations of her art (no lesser one preferred to a greater) that she can stir us so utterly as to stand, beyond all suggestion of comparison, the greatest actress of the age.

Ibsen and Duse

THOSE times are not, though, hers to comJL mand, and are certainly not ours to purchase. With the advancing years too (this is one of the few penalties that anno domini does exact) bringing deeper vision, they must occur less frequently. I suspect that it was a growing misunderstanding between herself and her audiences upon this important point which led to her retirement, which accounts now, perhaps, for the severe reception that she gives to their most respectful applause.

But in The Lady from the Sea, at least, Ibsen himself is much to blame. He, like Duse, could not tell artistic lies. And when, his play's second act being achieved—every apparent chance given it, sound construction, good character drawing and the like—it yet refuses for some reason to come to life and to carry him then (so it should seem) by its own impetus to its own end, he can but reason out and round off his story, point his moral, and tell us in effect (as Duse tells us in acting it) "This is what I meant the play to be." It is no use grumbling. We must remember Rosmersholm and The Wild Duck, and if that only deepens disappointment, must remind ourselves that Ibsen's worst is, after all, better than many another best. A strange thing, this breath of an artistic life, without which the dry bones, however well articulated, will not live; and not the greatest son of man can command it. We may ruthlessly refuse to consider as a work of art the book or play or poem that is not informed by it. And the boon is often granted to the simple and denied to the wise; wherefore the wise know that striving will not win it, once it has passed them by.

We may equally say to Duse " If you don't feel tonight that you can really let yourself go in the last act, please don't trouble to play at all. Let the management turn on a cinema instead." She would doubtless be grateful if we did; though even more grateful if we could tell her how to command creative inspiration, how to turn herself from a mere woman into a goddess. Lacking that wisdom ourselves, we may be wisely grateful for her refusal to pretend to the power, for her utter rejection of charlatanism, even for the hardly disguised contempt with which she greets what must often appear to her to be our childish, inarticulate pleading to be taken in.

Her Dynamic Repose,

BESIDES, so much is left. Indeed, her art is left. I write now having in mind a younger generation of English-speaking playgoers that may never see her. It is ill describing such art. One can catalogue its virtues and praise them one by one more or less intelligently. There is the constant purpose of movement. In the flash of a second before she moves she seems somehow—though really I cannot guess how, the thing's fantastic, inexplicable—so to warn you of what she is going to do that you are primed to watch if and to catch at its meaning; therefore, the thing done, there is never a doubt what it did mean. Clarity is the greatest of virtues and, Heaven knows, the hardest to come by. She has perfect repose; and I have never seen her still without the stillness being as fully charged with life and meaning as is any movement.

Her gestures—I must use a metaphor familiar to staleness—are like the ripples caused by a stone thrown in a pool. They flow outward from their center without effort, with perfect adjustment to the force of the impact of emotion or thought that causes them. Her hands and their beauty have been celebrated by poets; but the most prosaic observer may note their sensitive strength and how she employs them to express finality in emotion or thought —appropriately enough, for in them, so to speak, physical expression reaches its natural limit—while her voice and her face are registering in changing tone and flickering play the varying intentions, the less certain impulses of the scene.

Duse absorbs the material of her part. The dramatist will have registered it for her in print as best he can. But, for the hundred implications that lie behind the stark sentences, there is no recognised notation. Nor, when she has divined these, and often it will be, enriched them for reproduction in-the human medium, is there any language of record by which to detail the ultimate product. It would be interesting to set a skilled observer to the task of inventing one. He might devise something like the score of an opera; words, musical signs, even algebra and trigonometry might be brought into it. It would be interesting but futile. For if it is the penalty of the actor's art to be evanescent, it is its glory that it cannot be imprisoned in formulae, And, recalling as I write that first dialogue with Arnholm, I am aware that its artistry lay just in the fact that it defied description. The words were there, and the full stops and the semi-colons and commas, and there was tone and gesture and expression, eminently appropriate, But while you might intelligently note all of these in passing, in sum you were conscious of none, but only of Ellida Wangel and of your astonishing ability to see the woman through and through.

(Continued on page 100)

(Continued from page 55)

A Mistress of the Golden Mean

IT is, in fact, just when you do pick out L from this constant, but constantly changing, harmony a too arresting tone, a too definite gesture, that you may suspect her to be—the word is disrespectful, I am sorry—to be shirking an emotional issue. This breaks the spell, I cannot deny. Then, instead of noting, with so much of a slightly withdrawn mind as will serve for memory, the things well done, and letting the rest of your observant self relax at her bidding into unselfconscious sympathy with the character, the balance is changed; your sympathies fall dormant, your critical mind grows alert, comes forward and takes command, But even then, though differently, she can satisfy the critic; defeat him, moreover, for all his keenness.

To watch her treatment of the scene with the Stranger was a lesson in the sheer artistry of acting, if nothing else, The unerring power that she has of pitching a dialogue in the right key, and of sustaining it there at will; musically, never monotonously, never sharpening vor flattening the note unduly; slowing it "may be or quickening, but never slackening or hurrying her chosen pace—that is a delight. She is the mistress of the golden mean. I fancy that one reason why she seems to shirk climax is that she often finds the more level passages in a part richer in content, more fruitful, for her, in interpretation. Does one not sometimes hear a great pianist treat a purple passage with apparent indifference, while he will give great care to what the commoner man will neglect? How many hundreds of people can rise to a moment, how few have the strength of artistic character to give us the sustained beauty of treatment in which is really to be found the ultimate pleasure that the educated mind can receive from a work of art. You will never, it is needless to say, find Duse doing anything clumsy or inept. But you can find her doing things of the least consequence with a perfection of accomplishment.

These may often escape you, for she mostly means to escape you. She would prefer—and you should prefer—that such delicacies of detail should be lost in the effect of the whole. She does not, indeed, do them for you, but for the part's own sake. Without them, though, or rather, without her wish to do them, that total effect of beauty, of power moreover, would not be achieved.

One reflects on her power. It is curiously concealed as a rule within the golden mean. One remembers the moment in Magda when she turned on the complacently apologetic seducer, a time in Iledda Gabler when she stood watching I.ovborg and Mrs. Elvsted, other moments enough when power flashed out; though, even then, never nakedly, never so astonishingly as to destroy the harmonv of the scheme within which she was working. ⅛ The Lady from the Sea there is but one quite decisive passage which begins when Ellida receives her freedom (and this I confess she indicated rather than realised) and ends with her handshake for Wangel (but that simple thing she made the finest thing in the play), She diffuses her power, gives it, so to speak, unconditionally to the character, as generously as she has at one time given every faculty she has.

Once or twice—conscience drives me to these reservations—I seemed to detect in an uncalled for sharpening of tone a touch of the dictatorial attitude of the "star" actress. Just once she moved round Wangel less as if he were a man than a lay figure. It only goes to prove that Duse, like the humblest super, needs a theater to work in, a State in which she should be but the first of the State's servants. And as, in all these years, she has never had one, has been, instead, idolised and isolated in the public worship in a way that might have turned the head of the Pope himself, what a record of respect for her art lies in the fact that, closely as I watched, I could detect no larger lapse,

Generosity, and the power to give; in this lies, I think, her master secret. And, if this is so, my sudden question whether acting is, after all, an art to be practised in maturity, is answered fully. The young person yields, generously indeed, but recklessly and ignorantly, to impulse, But Duse knows what she gives, and will give nothing but what she knows and has appraised. And—even for any parsimony which time may now force on her—which is the greater gift?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now