Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

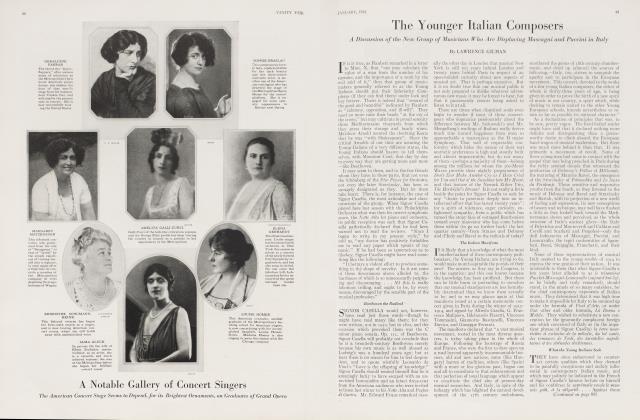

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowA Famous Novelist's Analysis of Recent Changes in French Ideals and Manners

January 1923 Marcel PrevostTHE younger generation—and by that I mean the generation that has grown up Jsince the war—is being pretty sharply criticized everywhere. Not only in France, but in every country—if one may judge by opinions expressed in periodicals and books— young people constitute a problem that bewilders and rather alarms the older generation.

First of all let me say that I am absolutely in sympathy with the new generation. It is full of life and enthusiasm, it is audacious and original. Besides, the fact that customs change does not necessarily imply that they change for the worst. Nothing could induce me to plead for the past against the present. But at the same time I consider it useful for both old and young to take mental stock of their differences in order to determine, each one for himself, which attributes he considers worth cultivating, and which he looks upon as faults that should be discarded.

In judging the new generation we of the former must always remember that these young people grew up too quickly. They experienced in five years what we experienced in a quarter of a century. The hectic conditions caused by the war developed their minds and imaginations abnormally. At the same time, because of their very youth, they were spared responsibilities and obligations which would have offset the exaltation which stimulated and unnerved them. They had no definite, effective outlet for their activity. They were left very much to themselves. They lived in their own world, so to speak, with nothing to prevent them from believing in their own importance, their own intelligence and in the incomparable superiority of the ideas which they thought new because they had never heard of them before.

OF course I can speak only for France, but I know our own young people pretty well. And I imagine that in many ways they are like young people in other countries. At any rate, in France, there are very great differences between the outlook on life of the present generation, and that of its parents. It seems to me that these differences may be divided into three general categories:

1. In regard to authority. There has been a reversal of authority. The relations between children and parents, teachers or older people in general are practically the opposite of what they were a generation ago.

2. In regard to money. Money has come to play a vital role in young people's ideas of life— something it did not do in their parents' time.

3. In regard to social conventions. Because it has been left so much to itself and has been given so much freedom, the present generation has acquired a standard of social conventions very different from that of its parents.

As it is impossible to study all three of these in one article, I shall, for the present, merely try to set forth the main points of the first two, i. e., the question of authority and the question of money.

French family discipline was based, in the past, on two principles: 1. that the wife should obey her husband; 2. that the children should obey their parents.

According to the code, the wife is still obliged to promise to obey, but such obedience does not exist in reality. If you watch the couples as they come up before the maire to get married you will soon realize what a farce the words of the ceremony are. When the wife is asked to promise obedience she makes no attempt to hide the irony of her "yes," while the husband invariably assumes that silly embarrassed look which a man has when he is placed in a publicly ridiculous position.

ALL women rejoice in the breaking down of the husband's authority. But probably they do not realize that by doing away with it they paved the way for the suppression of paternal authority. Forwhen children lost respect for their father's authority the mother's position soon became as weak as that of the French kings after the power of the nobles was broken. Besides, everything hangs together. In a society where authority is supposed to reside in numbers rather than in position the family is bound to reflect the common ideal.

The emancipation of children began before the war. But the movement was started by the parents rather than by the children. It consisted principally in this: Instead of looking upon childhood and youth as periods of preparation for life, as people did in my time, parents, before the war, became more concerned about how their children played; and less about how they worked. The ideal was no longer to make Roger learn his lessons, but to let him play and "develop" his youthful "individuality."

Parents themselves, by their own weakness, started to break down the principle of authority. They fostered in their offspring the idea that youth is not a period of formation, of preparation, of temporary abnegation with a view towards future enjoyment, but a period of real social and individual life, a reduced image of grown-up life, containing its share of rest, pleasure and remuneration. Naturally young people began to imagine they were somebody and were justified in claiming individual and social rights.

THEN came the war. It had a double efJfeet on children ranging from seven to fifteen. In the first place it broke up and upset public instruction and even family training. Homes and schools were disrupted, fathers and mothers separated. In the second place it caused a sort of forced maturing, due to the fact that boys and girls only a few years older— from sixteen to twenty—were suddenly thrown out into the world as full-fledged human beings. Boys of eighteen were sent to the barracks, girls of sixteen or seventeen were busy with war work in the rear. With one bound the children of 1914 jumped the grades made empty by the war. And in families where the father was away and the mother burdened with unfamiliar tasks and duties it was natural that the younger children, spurred on by the independence acquired by older brothers and sisters, and left very much to their own resources, conquered their liberty, affirmed their rights and finally founded the regime of youthful democracy.

This evolution is very important in so far as it constitutes a revolution of principle. Young people have replaced the autocratic parental regime by a democratic regime where parents and children share authority in much the same way as various factions share authority in a democracy. Some people might go further and say "Soviets." I would not go so far as that, although the evolution tends in that direction.

I am not trying to indulge in paradoxes. I merely wish to lay stress on what I consider a very characteristic evolution. Just as in France between the publication of Eugenie Grandet and the end of the XIXth century a change occurred in domestic relations which made family decisions no longer reflect the husband's wish but the agreement of husband and wife arrived at by discussion, so, today, a change is taking place which makes decisions concerning young people subject to agreement between parents and children. This constitutes more or less of a revolution. Before, young people's wishes counted for very little in the family government. To-day they have an enormous, one might almost say a preponderant influence.

Naturally there is no question of councils or meetings of .parents and children. What I mean is that parents no longer decide things without first consulting or sounding out their children about matters that concern them. They rarely oppose their children but give in to their will.

WHY? In the first place out of laziness. W Modern life is so complicated and strenuous that at a certain age every person longs to be left in peace as much as possible. Parents, like other people, try to avoid scenes and complications, especially with subordinates, i. e., children and servants. No one asks Henriette whether she wants to go to the dance (where society is rather too fast for a young girl), but she is taken along because her parents know that if they didn't take her she would be in an execrable humor for days to come. And as no parent cares to take the time or trouble to punish Henriette for showing her displeasure, it is much simpler to let a pleasant Henriette spend a few hours in rather doubtful society than to have an unpleasant Henriette spoil one's own society for weeks or at least days.

Every day I hear parents say with conviction, "I took Gaston out of school because he doesn't like Latin," or " We simply had to buy Maurice a motor cycle." And their tone shows that they are not expressing affectionate regard for their children's wishes but the bitter necessity of giving in to a stronger will. It is exactly as if they said, "I had to give the cook a raise," or "We couldn't stay longer in the country because the servants didn't like it."

Parental abdication, therefore, is partly founded on laziness.

It is partly founded, also, however, on another feeling, a strange deformation of the parental instinct. As soon as their children begin to acquire an individuality, modem parents seem to imagine this individuality far more precious than their own. They seem to think it their duty to develop this individuality at any price, even at the cost of their own personalities. Never have parents been more convinced of their own uselessness, except as instruments in handing on the torch of life, than at the present time. With a positively amazing altruism, which nothing justifies, modern couples of forty-five feel convinced their own evolution is over, while their children's is sacred.

This is sheer nonsense. The evolution of a group of children ranging from io to 20 is only a preparatory phase. Whereas the evolution of a forty-five year old couple (unless it is deliberately stopped) is in its most productive phase.

BECAUSE it is so widespread, parental abdication has led young people of to-day to believe that youth forms, so to speak, a class of its own, entitled to its own social conventions, customs and rights. I defy you to find a single family where you can prevent young people from doing something they were allowed to do once, or from doing something their friends are allowed to do. The younger generation feels like the labor unions, There must be no backsliding.

In other respects, too, the young have adopted the principles of the labor unions, They feel, for instance, that no one must interfere with their liberty, whereas they have the right to embarrass everybody else. Girls and boys feel exactly the same on this point. Their dogma is their invincible belief in their own importance and wisdom as compared to their parents' mediocrity. If you draw them out a little you will be amazed to find how cocksure they are of themselves and how convinced they are that their view of things is the only right one.

One might think such a situation would cause family clashes. One might think that modern children would be unbearable, and their parents very unhappy indeed. But not at all. The children are affectionately overbearing, and the parents are delighted. Henriette's mother lays stress on the fact that her daughter "is more a friend than a daughter," and when she thinks of the awe she felt for her own mother, at Henriette's age, she feels very proud of Henriette's independence, acquired at the expense of her own maternal authority. Henriette, on the other hand, admits that "mother's a brick," but in her heart she feels that the credit for the sympathetic association is due to her, Henriette.

At present, then, there is apparently no discord in the home. On the contrary, everywhere, we see signs of that idyllic truce, that idealistic enthusiasm which precedes all revolutions. The former rulers savor the sweetness of their abdication, the ruled of yesterday revel in the glory of not obeying.

I do not foresee any tragic consequences of the revolution of the young. But at the same time I think the ground is getting slippery and that it may be time to put on the brakes if only in the interest of the young people. Let us cite two examples: the increasing indifference to study, among boys, and the immoderate love of clothes, among girls.

To take the girls first: it is true that our girls formerly dressed far too plainly, Until she came out a girl was dressed in the simplest—often the ugliest—clothes imaginable. But if that was wrong, the modern system is equally wrong. It is just as absurd and shocking to allow girls to dress as they do to-day. It is sheer nonsense to spend as much time and money on the dresses of girls ranging from 13 to 18 as on those of their mothers. But that is not the way girls feel. Their one ambition is to buy as many pretty gowns and as beautiful lingerie as women ten, fifteen or twenty years their senior, not to mention artificial aids to beauty!

But as most young ladies do not have large incomes at their disposal, they cannot afford to be as sumptuous as older women. Consequently they are obliged to limit their extravagance to the least costly adjunct to dress, i. e. paint, powder, lipsticks, and imitations of the latest extremes in fashion which mothers usually tolerate in order to have peace. The result is quite amusing. It is a very droll and yet characteristic type, that of the young woman of to-day, who imagines she's as smart as a grown-up lady and in reality looks like a cross between a prewar young maiden and a chorus girl. Aside from the fact that there may be disadvantages in allowing a morally recommendable young child to look like an adventuress, the main objection to this strange ideal is that it is apt to instill an insatiable longing for money in a girl's head. As most girls can never afford to buy the pretty things they want, and as they think that money alone would enable them to be beautiful, striking and popular, they very frequently get the idea that money is not only useful but essential. This, it must be admitted, is regrettable.

As for boys, their general education suffers badly as the result of the modem tendency. It is quite right to encourage athletics but one may go too far. A grown-up man may be bored by certain physical exercies which he considers necessary to build up his health, but all forms of exercise may be regarded as amusements, when it comes to children, A fifteen year old boy will always prefer football to Greek analysis. Therefore children naturally try to convince their parents of the value of athletics—and as the modem parents naturally give in to their children, tedious studies are abandoned without much opposition, On the other hand, it must be admitted that the present generation is superior in many ways to those which preceded it.

In the first place, its freedom has made it less unprepared to deal with life. Young ladies of 1922-23 are much more practical than their mothers were, they are not apt to be carried away by romantic ideals d la George Sand, and young men are more awake to the danger of falling into vulgar temptations. Liberty of action has developed a sense of responsibility, The only drawback is that a too precocious sense of realities may destroy the charming constructions of dreams and fancy which used to delight our own youth. To-day a high school pupil has a man's outlook on life, a young girl is a near-woman. Both of them have tasted too early the curiosities, pleasures and diversions of social life. They have jumped a grade, so to speak. Yet that grade had its charm. Because they had a mentality of twenty when they should only have been sixteen, the present generation doesn't know what it means to be sixteen, in, the way we knew it. That delightful anticipation and fear of life, that inexpressible hope tinged with timidity which characterized Ren6 or Dominique will never be theirs. When they read about it in Chateaubriand or Fromentin they will not understand it apd probably find it absurd. Such is the way of life. It is useless to try to stop evolution. However, although I admire the young people of to-day and watch them with affectionate curiosity, I cannot help confessing that I don't envy them,

(This is the first of two articles by M. Prevost. The second will appear in February.)

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now