Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTaking Out No-Trumpers

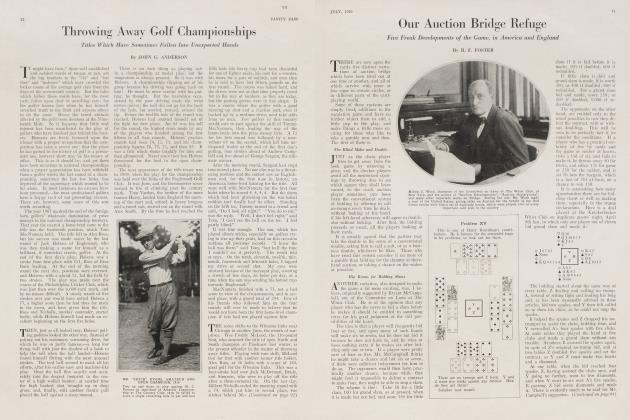

R. F. FOSTER

Some Current Auction Bridge Theories Which Are Not Supported by the Facts

BOTH science and logic agree that in the investigation of any disputed point the facts must be carefully examined, to see if they agree with the theory. If they do not, the theory is the thing that must give way. I believe I am one of the few writers on the game of auction bridge who has no personal opinions except those arrived at after a careful examination of a great number of facts.

In 1916-7 I examined a large number of deals with a view to determining the value of the following rule:

"Never leave your partner in with a no-trumper, if second hand passes, when you have any five cards of a major suit; no matter what they are, or what the rest of the hand."

I call this the invariable take-out; one of the few rules to which there is no exception, when the original bid is only one in no-trumps. I have given my reasons for it in books and articles, and these reasons are founded on facts, obtained at a great expenditure of time and labor. I have never found any reason to change my opinion; but in justice to readers of this magazine I must admit that not a single American writer agrees with me. The English writers, on the contrary, go even further than I do, and are advising the take-out with any five cards of any suit, whether major or minor.

The following inquiry is confined to major suits.

Here are the opinions of a few of the best known writers on the game:

WHITEHEAD. Take out with any five cards of a major suit as good as an original bid; or with a singleton and any five cards of a major suit that is as good as a defensive bid; or with two five-card major suits of any description.

Work, The major suit take-out is limited to strength. It should be made only with real strength; not merely an average hand that happens to contain five cards of a major suit. The best rule is not to take out partner's notrumper with a major suit unless the suit contains at least two of the four top honors, and the whole hand seems sure to furnish a minimum of four tricks for either the notrumper or the major suit.

Shepard follows Whitehead, and adds: "We can sum up the results of five-card take-outs from weakness as follows: Any suit headed by a card lower than the jack, or one headed by the jack, will be set more often than the no-trumper. The no-trumper will win more games and hence will yield larger scores than the weak take-out."

Mr. Shepard's book isfull of mathematics and statistics, but there are no figures to show just how much oftener the weak take-out will be set; nor just what the difference will be in the score. A tabulation of results from 500 actual deals would be valuable, as confirming his statements.

Denison. This writer has nothing definite to say about the major-suit take-outs; but in his example hands he shows that he does not approve of them. See, for example, Nos. 34, 53 and 72. He takes out with the two-suiter, which every writer agrees on.

Irwin. This writer gives examples, rather than precepts; and seems to advise taking out with major suits on strength, or on a greater length than five ca-rds, six or more. Her example has seven small cards.

Bridge Problem LIV

McCampbell has nothing definite to say about take-outs, his advice being chiefly about original bids and doubles.

Metcalfe says nothing about anything but the warning with a worthless hand.

Clark gives examples only, and they are all strong in the major suit; or have strong outside cards, at least four tricks.

McColl says to overcall with a long unestablished "red" suit with no reentries. Nothing is said about major suits as such, or about spades and clubs. Why a " red " suit?

Ferguson limits the take-out to suits of six or more in a major suit. He adds: "In the earlier years of the game it was considered good strategy to take out partner's no-trumper with a particularly weak hand, holding five hearts or five spades. This practice has been practically abandoned. Let your partner alone if you hold no high cards, and hope with all your might that the others will let him alone."

Cochrane says: "A hand containing a worthless five-card suit, with no outside strength will not average to win enough extra tricks with that suit as trump, instead of as assistance to no-trumps, to pay for the increase in the size of the declaration. The general rule is: Take out your partner's no-trump bid with a major suit, if it is as strong as an original bid; or six cards."

ALL this is theory. Not a single writer offers any facts in support of his views. I never attach much importance to opinions in card games, as I find they are usually based on limited or on one-sided experience, especially one-sided. When one gets down to brass tacks for the basis of an opinion on any rule in a game of cards, it usually comes to, "We always played it that way."

I have found upon personal inquiry among several of the writers quoted, that not one ol them ever gave a fair trial to my rule for taking out no-trumpers. They are satisfied that their theory is correct, and they refuse to try another, therefore their experience is one-sided. They are like the golf player who insisted that there was no necessity to use wood, as he could do better with an iron, but who had never given a wooden club a fair trial.

As the result I spent a summer in analyzing take-outs, and, thus far, no writer has produced any facts to contradict my rule. The usual talk about having analyzed "thousands" of hands which some writers put forth is, much of it, rather theoretical. It takes me about an hour to analyze three, or at the most, four deals, using my own invention, which is the fastest method possible: transparent paper over a diagram.

This summer, to assure myself that my previous examination was not in some way at fault, such a large percentage as 50 points a deal being rather impressive, I undertook to analyze 500 fresh deals. All deals in which the second hand interposed a bid or double were eliminated. All deals in which the fourth hand made a bid after the take-out were disregarded, unless this bid would not have been made had the third hand passed, leaving the no-trumper alone. When the take-out has influenced further bidding, it must be considered. Cases in which the fourth hand would have asked for a lead in case third hand had passed—and bids the suit after the take-out—are evidently not affected, as the 110-trumper is taken out in either case. All deals with more than five-card suits are disregarded.

THE result of my analysis simply confirms the examination made six or seven years ago. In 500 deals, the invariable take-out with any five cards of a major suit, regardless of the rest of the hand, shows the following results, giving the best possible play for each side on either declaration. All deals in which the other side would have got the contract against any bidding, were thrown out.

In 500 deals, the no-trumper if left alone by all three players, or if it returned to no-trumps after the take-out by third hand, was set 93 times; was good for the game 214 times, and good for the contract, but not the game, 193 times.

The variation in sets was from 20 points to 230. For games, 125 points were always added, as in duplicate. Incidentally, it may be mentioned that there were 23 cases in which the no-trumper would have been set, had the adversaries not taken the contract.

In 500 deals, in each of which there were exactly five cards of a major suit in the third hand, second hand making no bid, there were 412 take-outs; 48 returns to no-trumps by the dealer; 23 shifts to another suit by the dealer, and 17 adversaries' contracts due to the take-out.

Out of 500 deals, the take-out made no difference in the score 63 times, as the cases the take-out showed a loss, as compared with leaving the no-trumper alone. In 329 cases it showed a gain, in favor of the take-out. The take-out was set only II times in 500 deals, as against 93 times that no-trumpers were set.

(Continued on page 102)

(Continued from page 76)

In the scoring, adding 125 for a game won on the deal, the invariable take-out gained 34,568 points; and lost 8,241 points by not leaving the no-trumper alone.

This shows a balance in favor of the invariable take-out of 26,327 points in 500 deals, which is an average gain of a little more than 5 21/2 points a deal, or a little more than I found six years ago.

Taking the deals in lots of 50 each, the greatest gain was 3,858 for the take-out, from which there was a loss of 766 to be deducted, leaving a net gain of 3,092, or more than 60 points a deal. The smallest was 2,880, less 830, or 2,050 net; an average of only 40 points a deal.

The greatest loss for the take-out in any one deal was 155 points. The greatest gain was 330.

It is only fair to add that in all these 500 deals in which the original no-trump bid has been taken out by the partner with two spades or two hearts, the original bidder, holding the no-trump hand, would not allow the take-out to stand unless he could support it with at least three small of the suit; or two cards, one as good as the queen. Failing this essential support, the original no-trump bidder will, of course, either return to no-trumps or call a suit of his own, in case there is no bidding by the oponents. In many cases this entails a loss which has been duly considered in the foregoing analysis.

In the course of this long and tedious analysis, it may readily be supposed that some very interesting hands came to light, some of which will be given in a future article, illustrating, as they do, both sides of the question.

Answer to the November Problem

THIS was the distribution in Problem LIII,in the November number:

Hearts are trumps and Z leads. Y and Z want six tricks. This is how they get them:

Z leads the smaller of his two spades, which B is allowed to win with the queen. If B returns a diamond, Z trumps it, leads the ace of clubs and then his remaining trump. If A discards a club on the trump lead, it is clear that Y can get in and lead through B's clubs. If A discards a spade, both Y's are good. Therefore A must discard a diamond, in which suit B has the winners. Y sheds a small spade, and B a diamond, Z now leads the spade seven, which Y wins with the ace. Now B must discard the ace of diamonds and give Y a trick with the four, or let go a club and give Z two tricks in that suit.

If B returns a club, instead of a diamond, at the second trick, Z holds it with the jack, and leads a trump. All three players must discard diamonds. Z leads another trump, and the same position arises as when B led the diamond and Z trumped it.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now