Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

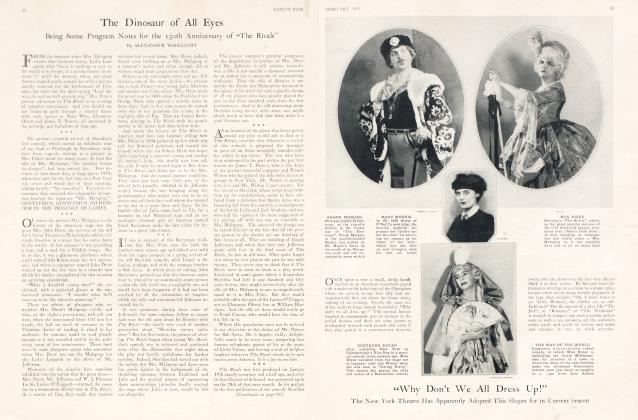

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe New York Playgoer Erects a Theater

The Good Folk of Manhattan Build the Temple of Their Own Ideal

ALEXANDER WOOLLCOTT

THE season of 1922-23 has receded into the annals of the New York stage. By this time in 1930 most of all its tremendous trifles will have been forgotten, and the inveterate keepers of scrap books will turn to the yellowing programs of the past Winter and wonder vaguely what all the plays were about and what ever became of all the young actresses who, one each week, were hailed as the logical successors of Mrs. Fiske.

A few things we shall remember. Probably we shall remember the beauty of the playing by that wistful troupe from Moscow. We shall remember the high, startling flare of Jeanne Eagels in the remarkable play called Rain. We shall remember long after 1930 the caressing loveliness of Jane Cowl as Juliet, and in the hearth corner will one day tell our grandchildren they are upstarts for thinking that this son of Margalo Gillmore's is anywhere near so good a Hamlet as was John Barrymore back in 1922, when Harding was President of the United States and a man said to have been called James Hylon, or something like that, was actually Mayor of New York.

Yet all in all, I think that the shrewdest, most interesting and most memorable performance of the year was given by no playwright or no player. It was given by the New York theatergoers—the same berated citizens who stayed away in droves from the Equity's unwisely managed theater and who could not be induced for any consideration to contemplate the American National Theater in the throes of Marjorie Rambeau's As You Like It—these same refractory playgoers, who turned away and busied themselves in the building of a theater more to their taste.

Feeling more than a little undernourished by the fare laid before them each week by the regular theatrical managers, they met and decided to build a home for their own Theater Guild. As the people of another land and another day gathered together and out of their own strength and devotion flung up toward Heaven the matchless wonder which we know as Chartres Cathedral, so the good people of New York met on the village green, rolled up their sleeves and started in to dig the foundations and haul the stone for their first community theater.

Boredom as a Constructive Impulse

THIS may be a slightly misleading account of the proceedings. The twentieth century goes in rather more for indirection than did the thirteenth, and the actual process in this instance was tumultuously to oversubscribe a $500,000 bond issue and leave the heavy lifting to others. But the spirit was not so different as one might think. And as at Chartres, while every sinew was lent to the hauling of the stone laden wains, the carpenters contributed their own craftsmanship, the stoneworkers and glaziers and weavers theirs; and the drovers and lawyers and plowmen threw in their purses, that they might have a share in the building, so, if you could look through the long subscribers' list of the new Guild Theater, you would find all New York—its wise men, its peasants, its fat burghers, its scribes—all joining forces in this one enterprise.

Shopkeepers, poets, teachers, nurses, dramatic critics, doctors, bankers, comediennes, politicians—they are all there. Out of the 1500 subscribers, it might be well to give a few names, to show how varied and how interesting will be the ownership of the new theater when its doors swing wide in the Fall of next year. That is good journalism. As the late Mr. Laffan of the New York Sun sometimes had to remind his arty young reporters when they would bring in their impressionistic accounts of the great banquets in town, there is nothing quite so descriptive as a list of names. Indeed, he once posted a peremptory order that every reporter covering a dinner would have to clog his lyricism to the extent of naming twenty from among those present. There was a broad grin in the Sun office next morning when a story, identifiable as the work of the wild Mr. O'Malley, wound up thus:

". . . and Louis Wiley, which makes exactly twenty."

Well, then, among the owners of the new Guild Theater, you will find Edna Ferber, Sir Edgar Speyer, Mrs. Fiske, Oswald Garrison Villard, Margalo Gillmore, Truly Warner, Ernest Peixotto, Genevieve Tobin, Adolph S. Ochs, Louise Closser Hale, Jascha Heifetz, Kenneth Macgowan, Joseph Urban, Joel E. Spingarn, Roy S. Durstine, Adolph Lewisohn, Mrs. James Harvey Robinson, Samuel Shipman, Arthur Guiterman and Sir Joseph Duveen.

The 1500 subscriptions range all the way from S100 to $10,000 bonds. The Sio.ooo bondholder has, I believe, some extra privileges. His name is emblazoned in the lobby as a Founder, which, of course, pleases his aunt immensely. Then he can go to all the first nights, and his nieces can attend all the final dress rehearsals. Also, Helen Westlev will bow to him on the street. (One of these Founders, by the way, is so recent an addition to the solid citizenry of Manhattan as Jascha Heifetz, for the money which his young and magical bow charms out of the wondering pockets of the world is usually spent in such luxuries as subvening the swooning drama or buying first editions of Dickens.)

A Record of Practical Idealism

THE ready response to the Guild Bond issue was due, of course, to its three-year record of bold, intelligent, resourceful production -its assumption that, whereas there were plenty of people who would just love Abie's Irish Rose, there were enough others who might prefer Andreyev and Ibsen and Shaw. The Guild has staged some feeble pieces and some that were hopelessly alien. But it also has brought to New York (and eventually sent out over the country) such plays as John Ferguson and Jane Clegg, Mr. Pirn Passes By, Heartbreak House, He Who Gets Slapped, Liliom and The Devil's Disciple.

Where it has made a pot of money on a piece that proved unexpectedly popular, it has blown it in on one so costly that it could only lose. Thus the rich, painstaking and defiant revival of Peer Gynt was in the natlire of a gift from the Guild to New York, and certainly the reckless production of the longest play in the language, Back to Methuselah, was a gift from the Guild to Bernard Shaw. The Guild knew that this five-part history of the human race could not possibly make expenses, but the Guild also knew that while a Shaw lives in the world, the theater owes it to him that no play of his, however perverse, should lie mute upon the shelf. So, making up its mind to endure unflinchingly a loss of $30,000, the Guild staged Back to Methuselah. As it turned out, the loss was only $20,000, which led Shaw to assure the not altogether convinced Lee Shubert that the play had made $10,000.

And, as a matter of fact, Shaw was too modest. It was the disposition the Guild showed in dealing with that play which fired a good many playgoers to the subscription point when finally the hat was passed. Indeed, in a (light of actuarial imagination, I should say that the revival of Back to Methuselah alone inspired $138,600 of the bond issue.

The success of the Guild is all the more interesting because of the disaster that overtook during this past season two other enterprises which, consciously or unconsciously, had been inspired by it. The Equity (the actors' union) brashly rented the Forty-eighth Street Theater and started on a similar scheme of production, but it was weighted down by the delusion that it should produce only original plays and, at such short notice, it did not find any that amounted to much. As one after another of these second-rate pieces were conscientiously produced by the Equity, one wanted to thrust a nozzle into the air and howl with despair — despair that a non-commercial theater should be so witless as to put on plays like Malvaloca and Why Not? and Hospitality when this generation has not seen Cymbeline or Measure for Measure, when Candida and Man and Superman gather dust in the library and only the ancients have known the fun of Sheridan. If the Equity were to announce that next season it would revive Caesar and Cleopatra, Pinero's The Thunderbolt, Sheridan's Critic, The Poor Little Rich Girl, The Cricket on the Hearth and Henry V, I think it would not have to be turning to Laurette Taylor in the Spring and asking her to play for nothing to help its treasury out of the hole.

(Continued on page 94)

(Continued from page 39)

An Olympian Fiasco

THE other disaster was the one encountered by the Producing Managers' Association which, at the prodding of Augustus Thomas, got together a company, laughably called it the American National Theater, and started it off with As You Like It. It was a costly and languid revival of a not infrequently tedious comedy, fearfully imperilled at the start by the selection of Marjorie Rambeau to play Rosalind—the stunning Miss Rambeau, whom the awesome Shakespeare rendered so painfully self-conscious that one could not help recalling Brander Matthews' old reflections on "the mincing steps of verbal parvenus". The American National Theater played one week in Washington and one week in New York. Then it expired.

The delightful thing about the Guild's success is the contrast between its present fame and its lowly beginnings. Those beginnings were the funny, aspiring little productions made at the Bandbox Theater in the early part of 1915, for the Guild was formed out of the wreck which the war made of the Washington Square Players. When its new theater opens next Fall, there will be some in the illustrious first audience who will stop craning their necks long enough to sit back and remember the dingy little theater in East 57th Street, where performances at first were given only on Friday and Saturday nights, where the best seats were fifty cents, where Glenn Hunter, at a salary of $10 a week, acted away for dear life and slept on a pallet in the theater between shows, where the scenery might be by a young newcomer named Robert Edmond Jones (who had recently been a window dresser in Boston), where a new playwright named Zoe Akins was first heard from and whence, after the final curtain, company, audience, critics and all would repair to a Third Avenue saloon and talk till daylight.

That was only eight years ago, but that is an aeon gone at the present pace of the world. Probably in another eight years the young folk of the day will be laughing patronizingly at the stodgy, timorous old Theater Guild and wondering why the gaffers insist on going 'way down town south of the Park to sit through its fossilized performances.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now