Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowFreddie Comes Back

THOMAS BURKE

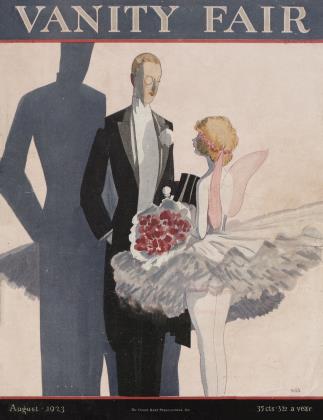

In Which a Popular Idol Discovers that There Are Some Things Fame Cannot Win

SILLY of Freddie Drumpitts to fall in love with that girl; those in the abyss will always look upward for happiness, when it is lying all around them. She lived in Clutterfield, where Freddie's company was touring. Her father was a magistrate, a prominent townsman—somebody; and she had been brought up in a two-thousand-a-year home High School, Brussels finishing school, At Homes, tennis teas, Nice People—everything that is something. Freddie was advance agent for the Kiss Me and Slap Me revue—everything that is nothing.

AND the idiot, meeting this girl, fell in love with her; and, on a return visit, told her so.

She turned him down? Oh, no. She dandled him. For twelve months she dandled him up and down the walls of his pit, while he for twelve months reached with vain hands towards the cool, suave world wherein she moved. You see, he was different. He had character. He had brains. These were new things to her. Uncouth, obscurely born, no money, no position, no hope of any—but he had brains; and although the clever may sometimes fail to recognize brains, the fool always sees and pays tribute.

She didn't want to let him go. She wanted his company, his fresh point of view, his illuminations. So she dandled him, without Yes or No, and slowly she destroyed him. By her austerity and pride of breeding she made him always conscious of the blight that he bore; always she answered his wooing with hints of the differences between their positions. She made him abject with a look; shot him back into his pit with some unconscious gesture of mother's drawing-room; degraded him with reticences and refusals; and fed him, by her letters, with a sense of utter self-loathing. It was as though she pronounced against him that greatest blasphemy against man—" Thou fool! " Once she told him he was vulgar. She did not tell him twice, having his eyes before her. Brutes kick dogs; fools only amuse themselves with them.

To marry him was unthinkable; but to let him go . . . Some secret voice in her heart forbade this. She felt that he was going to be something, and she wanted to be his friend and be proud of him when the time came. She wanted to be able to say "I knew him when—" and to show how she had been the inspiration and encouragement of his dark days.

But he wasn't wearing it. He was no timeserver for love or for anything else. Impetuous —that was Freddie all over. He settled the matter one night at the corner of the Square where her aldermanic father lived his aldermanic life. He shot one fierce question. She hesitated and played for an opening. He didn't offer one; he only repeated the shot.

"I don't know. ... I can't ... I value your friendship ... I think more of you than . . . But we're so different . . . You haven't any . . ."

He was gone. Round the comer and out into the little streets he went, leaving her idiotically with hand at hair, and face upturned in an imitation soul's awakening.

He was gone; and gone in such a state that at the theater he had rows with the touring manager, the resident manager, the electrician, and the star comedian. He told them all what their mothers were, and they returned his compliments, but with the added salt of telling him to see the treasurer and giving him precise directions to the way out.

HE took his money to the nearest bar and had, on the whole, a not-bad evening; and woke in the morning with a soured soul. He was despised and rejected. By her attitude towards him she had held him up to a diminishing mirror, and had shown him himself as a forlorn and ludicrous* object—a worm, not at home in the earth, squirming its head to the stars.

Crawling out of his back lodging in the early afternoon, thinking of ways to London, where he might bury and forget his shame, he fell in with Billy Hayhoe, a one-time bill-topper.

"Freddie, me boy, I'm thinking of America. I'm off. Chance me luck. What's your best news?"

Freddie told him.

"Like that, eh? Well, New York for me. There's chances, laddie. And if I can't act, I can stick bills. Why not turn it up and come along? Pluck from the memory a rooted sorrow and join up with Uncle Bill?"

Freddie made a husky explanation of the state of the funds.

"So? Well, well. Look here, laddie, I was going second, but I've got enough for two steerages. And two's better'n one on a prospectin' trip. If I do flop, I'd rather flop in company; and if you struck something and I went down, I should look to you to pull Uncle Bill up. What?"

They went; Billy, on a half-holiday from school; Freddie, bitterly, with a little thought at the bottom of his mind that some day he'd come back, and then they'd see what. They crossed. They landed. Within ten days Billy Hayhoe got a bookmg in a vaudeville team touring the smalls, and got Freddie worked in as foil and feeder to him in a cross-talk act.

Together they toured the minor circuits, and in the blithe companionship of Billy; and amid the sights and sounds and encounters of the American tour, Freddie retrieved his heart's ease, and the memory of the Midland girl slowly faded, and the bleeding wounds slowly healed. He shed his old skin and was reborn into something new and strange. He found his soul again; but he did something more: he found himself and his life's business.

On an inspired evening, weary of feeding Billy with the same lines, and the same gestures and the same attitude of society boredom, he worked in a little new business. Surprised at himself, yet surrendering to this mood of whimsy he let himself go, to the disgust of Billy, the mild amusement of the orchestra, and the intense excitement of a Hebrew gentleman in the stalls.

THERE was trouble behind when they came off. Billy went for Freddie in good style, accusing him of queering the act, stealing his laughs, of ingratitude, insubordination, and base unsportsmanship. And Freddie had no answer. He couldn't explain to Billy what it was that had led him on to misbehave himself; he didn't know himself; and while he was floundering for phrases, the Hebrew gentleman, in another part of the wings, was inviting a pogrom.

" I wanta see a man. I gotta see a man." "Well, what man?"

"The man in the last act."

"Warn't no man in the last act."

"Well, the act before. I wanta see 'im. Do I got to stand ere all night, talking to a fool, ain't it? "

"Why doncha say what yeh mean, then? You mean Billy Hayhoe?"

"Billy Hayhoe me backbone! I mean that lad what feeded him."

Well, Freddie was found by the Hebrew gentleman, who pulled him aside; and when Billy Hayhoe butted in to know what it was all about—he hadn't finished with Freddie then—the Hebrew gentleman pushed him in the chest; and when he came back to ask if he was expected to take that sort of thing from a schonk—but by that time the schonk had got Freddie outside the theater.

You know the rest. You know how Freddie Drumpitts, billed as Freddie Fonthill, made his first appearance in the legitimate as the miserable comedian. You know how he turned a dud play into a three-years full-house run.

You know how his small part of the first night grew until it was the whole play. You know how his fame spread through the world—even to England.

You know how there were Freddie spectacles, Freddie neck-ties, Freddie collars; how the young men about town cultivated the Freddie lounge and the Freddie spats; how there were Freddie biscuits, Freddie toothpaste, Freddie scent, Freddie cigarettes, Freddie jokes, cartoons of famous politicians as Miserable Freddie; Freddie toys; and, in the dancing-rooms, the Freddie Crawl.

And you may have heard of Freddie's triumphal return to England, with the full original company, to play his famous part in his own land.

BUT only two people know why the Freddie vogue ended so suddenly; why Freddie, in his own country, made such an abject failure in his famous part.

You may have heard of that royal re-entry, which sent all England crazy. His intention to visit his old home was splashed on the front pages of the dailies. The fact that he had booked his saloon was announced in the evening editions. Stop Press told us that he had boarded the boat. He was really coming. The boat had left New York. At intervals from mid-ocean wireless messages gave us news of his health, his clothes, his meals, his daily life on board. They even gave hints that the company was with him and was looking forward to opening in England; and the name of the leading woman was mentioned three times.

No monarch, no victorious general, no triumphant statesman has ever received such a reception as the country accorded to Freddie Fonthill. At the port of landing the mayor of the town put out on a tug to board the boat and greet the greatest comedian of his time. Pressmen and press photographers and movie men mobbed him. On the landing-quay half the population of the town awaited him and hugged him and kissed him; and those who could not reach him laughed and cried messages of love to him.

There was the train journey to town; special train, rose-decked and bannered. From station to station the news was telephoned, and every platform was alight with waving handkerchiefs and kindly eyes.

London! The crowd; the police who came to his rescue; the bombardment of his car; the ride through the mad streets to the hotel and the Royal suite that had been booked for him. The voice of London crying him good-will. Something in his throat choked him.

The entry into the hotel on the shoulders of two policemen; the rush upstairs; the rich drawing-room with balcony windows; the Hebrew gentleman flinging open the windows —"On the balcony, me boy!"—Billy Hayhoe, his secretary, standing by him with the basket of roses presented by the management.

He was equal with kings; he could smile at the obscure rich; he could laugh at his poor early ambitions and disappointments. Everything was at his command. He had money, position, fame, popularity. The world was at his feet. All doors were open to him. He could have the best that England could offer, without asking; and the world's women came to him for love. With hat off, and that famous head of golden short curls flashing in the sunshine, he laughed and smiled and bowed, and held out hands to the crowd, and threw them roses.

He had ceased from serving the pageant; he was now of it. He was Mr. Frederic Fonthill. This was his hour. He had paid for it; God knew with what bitterness of heart he had paid for it. But it was worth it. His pulses were drumming; his face was hot and pale; he was at the topside of bliss. Now, he could say to them, now what shall you say? Now am I any good? Now who's going to swear and sniff at the advance agent? If I did come out of the slums, what of it now—eh?

Ah, those voices were dumb.

JUST then, as he stood smiling upon those warm welcoming faces, a 'bus, diverted to the street at the side of the hotel, passed slowly by. Two passengers were on top: a placid woman and a boy about three years old at her side. The woman was plainly dressed in a tailor-made costume, and her hat was not of that season. She carried a shopping-bag; she had more the air of five hundred a year than two thousand a year. What drew his attention was that she was not looking at the crowd or the hotel; she seemed self-absorbed, aloof. Only when the 'bus stopped, unable to move farther, did she give a slightly acid glance at them, and a pat of irritation. . As he noted her, there seemed something familiar in the poise of the head; it reminded him of the girl in Chicago—the most wonderful girl of all—who was to be his next leading woman and his wife.

She turned then; he saw her full face. At this surprise encounter with a plain woman whom he had once found beautiful, and had long since forgotten, he suffered a little thrill of amusement; and with the thrill came the knowledge that he had never loved her. He saw now what it was that he had loved— her class and breed; the grace and serenity and assured, rightness of her world, which he had always desired and of which he had been always in awe. Today he was in that world—far above her bourgeois circle—easy, mellow, correct. He could smile down upon her now; and he did.

As he did so, she looked upward at the balcony—saw him—recognized him —looked from him to the crowd and back again—then, the assured rightness glowing from her eyes and her posture, she raised ever so slightly an eyebrow, shrugged—and looked away.

But he caught those two movements: he had seen them before, and he knew what they said. He took them straight between the eyes; and those in the street below saw the slim figure flush crimson, and then turn paler than before. He seemed to wilt. His poise deserted him. The smile vanished. For a few moments he remained, looking awkwardly about him, at a loss with the situation; then crumpled, and slunk into the drawing-room; while an uncomely Midland woman went on to King's Cross, glancing back at the mob cheering a mountebank.

An hour later the Hebrew gentleman—with tireless hands—was addressing the rest of the company. "Would ya believe it? Oi-oi! I ask ya! After all this—after the biggest thing that ever happened—Napoleon —Lincoln—Judas —Caesar—Admiral Wellington—don't it?— would ya believe it—there 'e is—the crowd outside shoutin' for 'im, and 'im sittin' at the table, sayin' nothin' but 'My God, I wish I was dead!' "

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now