Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowRe-enter, the Prince and the Princess

The Chronicle of a Season in Which the "Won't-You-Sit-Downs" are Spoken of Thrones

ALEXANDER WOOLLCOTT

ONE begins to wonder if our latter-day playwrights are not regaining a lost interest in royalties. Time was, of course, when any serious play was more likely than not to tell sad tales of the death of kings. A tragedy, to be a tragedy, had to deal with the rise and fall of princes. Latterly, the theater has shown greater concern with charwomen, pickpockets, shabby clerks and wistful bus conductors—their joys and their sorrows, their loves and their wives. But this season, at least, our theater is agleam once more with the pomp and circumstance of sovereigns. Queens and kings acknowledge graciously each night the plaudits of the enraptured suburbanites, and the children who scamper across the stage are little princes and little princesses.

Just as in the days when the favorites among all characters were those two frightened heirs apparent whom an unamiable and unavuncular uncle wanted choked in the Tower—the days, by the way, when, according to the old programs, it was hardly the thing to present, such scenes without the notation

The Duke of York . . . Miss Minnie Maddern—so, now, our stage is aflutter with small princelings in trouble.

But their pangs are modern and mild. Their only acute suffering, in one of the new plays, comes when they must watch their tutor writhing in the necessary tact of his embarrassing duty to instruct royalty about so agitating a character as Napoleon. And in another, the royal youngsters undergo no greater woe than that involved in a formidable and chaperoned lesson in bridge. Of course, the royal Bertie, whom all folk of just the right age still think of as the Prince of Wales, is, in still another comedy, obliged to confess to his lamentably Victorian mother that he's had dishonorable mention; that he has, in fact, been dragged by his royal heels into the common divorce court.

The Royalties Among Us

OF such stuff then, are the new plays made— The Swan, The Royal Fandango and Queen Victoria. The first is the exquisite work of that same Hungarian who gave us Liliom and, long ago, a fine, penetrating, rueful comedy called The Phantom Rival. Quite the nicest thing that has been said about The Swan was Marc Connelly's observation that it might have been written by our own Zoe Akins— which sagacious utterance, of course, was also one of the nicest things ever said about Miss Akins.

One of the less complimentary things that must be said about her, however, was that, whereas she might have written The Swan, she most certainly did write The Royal Fandango. This was a somewhat too shaky and undernourished little comedy which, for all its darts and flashes of delicate gavety, seemed no great shakes when it came to town in November, with Ethel Barrymore most fascinating as the scatterbrained Princess Amelia, engaged in sowing a royal wild oat.

Both Miss Akins and the Olympian Molnar look on their little kings and queens with ironic and tolerant amusement, not unmixed with a certain wistfulness in Miss Akins's case— wistfulness and a real relish. For she is one of the children of the world for whom all plays must have something of a child's wonder in charades, a quality this play possesses.

Affection, amusement, respect—these emotions struggle for the mastery of David Carb and Walter Prichard Eaton, the two Americans who have written Queen Victoria. One imagines them setting forth sternly to write a chronicle play of the Widow of Windsor— the funny, fussy, fearfully domestic little body whom life, in its most prankish mood, made sovereign of an incredible empire. And, as Mr. Strachey might have warned them, their task became complicated by an untoward circumstance. Bless them, they fell in love with their heroine!

They must have argued that, since an Englishman had ventured to dramatize Abraham Lincoln and Robert E. Lee, it was the least two Americans could do to make a play of Queen Victoria. And in such dramatizations of history far from home, there is a certain precautionary value. Just as Louis Parker's Disraeli ran for three years to prodigious receipts in this country, but rather timidly evaded the danger of facing a London audience, so it may well be that the procession of Gladstone, Melrose, Palmerston, Disraeli, Prince Albert and the like through the scenes of the new play in Forty-eighth Street would be less convincing to Mr. Walklev and Mr. Squire than to the enraptured Mr. Broun and myself. It will be recalled that, in an essay by which he sought to instruct the Germans of 1914 in the art of mendacious propaganda, Mr. Chesterton pointed out to them that they should be careful to tell their whoppers only to those who did not know the truth. In his patient way, he assured them that they might tell the Eskimo that the Sahara was cold, and the Egyptian that snow was green. But they would be reckless to interchange the aenedotes.

Continued on page96

Continued from page 33

Queen Victoria covers a span of sixtyyears. It begins with the chill dawn in Kensington Palace, when the frightened girl in curl papers and a nightie is hauled downstairs to hear the tidings of her succession. It ends with the moment in the Jubilee celebration, when all the flaming and encrusted dignitaries of the Empire kneel while the bent, quavering old lady mounts the throne. She tries to make them a little, proper speech, but she forgets her lines.

"I have tried to be good," she murmurs; and then, groping for more words, falls back instinctively and appealingly on the same ones. Just before the distant band strikes up God Save the Queen, and the final curtain comes slowly, slowly down, you hear her once again: "I have tried to be a good queen."

A Swan in Ermine

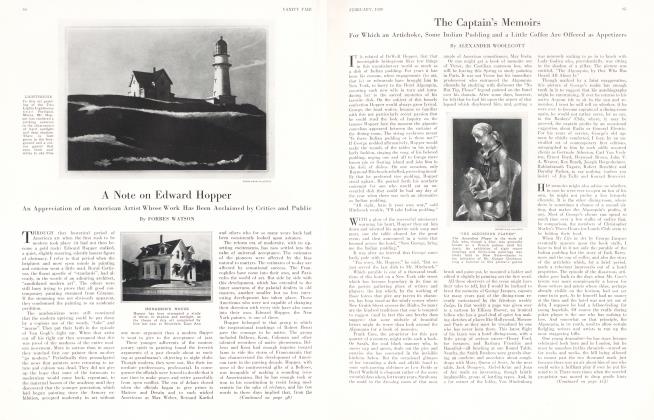

THE SWAN is a curiously detached and cool and silvery play—so written on the banks of the Danube, and so acted on the banks of the Hudson, that it is kept always a little remote from you, as though a line, impalpable gauze were hung between you and the heartache and aspiration on the stage. It spins the tale of a far-away princess who, directed by her matchmaking mother, indulges in an ancient device. She stoops to conquer. In order to arouse the interest of the only eligible heir apparent left in agitated Europe for her to marry, she lets her royal eye linger amiably on a young tutor of her mother's household. Unhappily for the mother's plans, the tutor flames up. And the cool princess catches fire. It is the old, old story of the great lady and the beggar, of the rose which the haughty Katherine threw to the tattered Villon, long ago.

It is all set forth this time with the finest reticence and economy of means. One yearns to take all the actors who belong to the Bull of Bashan School and set them down before The Swan, to let them learn how much more ringing a murmur can be than any shout. We would also bring along the playwrights who devise long scenes in which the leading man and the leading woman paw and maul and dishevel each other interminably. It would do them good to see how electric, how passionate, how blood-quickening, a single kiss may prove, when only one is shining in the play.

Just as Frank Craven, in The First Year, put to shame all his fellow playwrights who employ very arsenals of gats and cannon to unnerve an audience, when he showed with what agony of apprehension a theater can be filled by a really believable waitress swinging a humble vegetable dish too near the diningroom chair, so Molnar, in The Swan, fills his theater with a great excitement by the simple device of having his princess drink a glass of wine.

You see, all her great kinsmen are snubbing the frantic young tutor. And when, a novice in the routine of a grand dinner, he gulps down his liqueur at the beginning of the meal, they point out to him, somewhat brutally, that it is tokay he has thus squandered—tokay which is old and heady, and should, at the very end of the courses, be sipped with caution and elegance. He has so embarrassed and iostled them all in his rebellion, that now they greatly enjoy the ensuing evidences of his scarlet discomfiture. And you suffer with him, because, by this time, you have identified him as the spokesman of all commoners, appearing before mere crowns and power of place as the champion of the eternal and indestructible sovereignty of the human heart.

And so, when, in the disconcerting pause that follows, the slim, cool, white hand of the princess reaches out, deliberately closes around the thin stem of her own tokay glass, and lifts it to her lips for one magnificent gulp, you feel within you one of those great elations, the hope of which keeps you plodding to the theater night after night. If you are half a man, you want to get up in your seat and yell "Bravo!", which is Hungarian for "Atta-girl". If you are altogether a man and not too pitiably civilized, you do just that.

The Swan has been so translated by young Melville Baker that you can sit through it without a single afflicting reminder that it is a translation. Then, cast by Gilbert Miller and rehearsed by David Burton, The Swan is admirably acted at the Cort In this Cort chronicle, one would men tion, especially, the delightful performance of Philip Merivale as the Prince, and on a lower plane, of Alison Skipworth as the Queen Mother. Also, the happy choice of one Ilalliwell Hobbes, who must seem both a priest and a prince—and, mirdbile dictut, does. And Eva Le Gallienne is not bad as the Swanl which bird, you must remember, is ful, of grace and charm so long as it does not venture ashore, when it is only too likely to resemble painfully another bird. Some have said that she is as good in this as in that earlier Molnar romance which she played for two seasons, an observation that means much or little, depending on whether you thought she was good in Liliom. Personally, I thought she was pretty bad and, in the earlier performances, a little Buda-Pest slavey who seemed to have come fresh from Miss Spence's School for Young Ladies. At best, there is always something pinched and tight and fearfully conscious about Miss Le Gallienne's acting, and she has a maddening habit of playing an entire scene with her eyes fixed on a certain seat in the fourth row of the balcony on the side. She is a devotee of the cataleptic school, and some of us can't abide it.

Mr. Rathbone's Performance

BUT the best performance of all in The Swan is none of these. It is the playing of the tutor, by a tall, young Englishman named Basil Rathbone. I saw him first on a night in London, in 1920, when, under the goadings of Constance Collier, a curious agglomeration of Americans that included Herbert Kaufman, Ernest Lawford and myself, went traipsing to some outlying theater to see the hundredth performance of Peter Ibbclson. Compared with Lionel Barrymore's magnificent Colonel Ibbetson, that of Gilbert Hare seemed sadly feeble; but John Barrymore's place was more nearly filled by a gawky and towering newcomer from the provinces. This was Basil Rathbone. Later, he came to this country to embody the wild Cossack lad who caught the eye of the engulfing Catherine in The Czarina. Now he is the tutor in The. Swan — a greatly mellowed young player, who has measurably increased his mastery over his instrument.

The Swan, Queen Victoria, a magnificent new Cyrano contributed by Walter Hampden, Duse enchaining new devotees, and the Moscow Art Theater moving again from town to town—of such is the playgoer's fare in this country. It is not bad. It was, I imagined, never better. It is better now nowhere else in the world.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now