Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Hereafter and the Long Ago

New Sinners and an Old Time Saint Say Their Say in Two of Broadway's Interesting New Plays

ALEXANDER WOOLLCOTT

IT was just about twenty years ago that the late Mr. Beerbohm Tree was discreetly drawing men aside at the Garrick Club, in Bedford Street, to confide his new alarms about the sanity of little Mr. Barrie.

"Barrie has gone out of his mind, Frohman," he explained sadly. "I am sorry to say it, but you ought to know it. He's just read me a play. He is going to read it to you, so I am warning you. I know I have not gone woozy in my own mind, because I have tested myself since hearing the. play. But Barrie must be mad. He has written four acts, all about fairies, children and Indians, running through the most incoherent story you ever listened to. And what do you suppose? The last act is to be set on top of trees!"

That was the first warning that a play called Peter Pan had been bom. We can imagine similar misgivings in the minds of many theatrical managers to whom young Mr. Sutton Vane, sometime song-and-dance man of the provincial music halls, may have taken a play of his called Outward Bound, at which, as it has turned out, great, rapt, deeply responsive audiences have since been sitting both in New York and London this winter. Here was no celebrated and already prosperous Barrie, but the undistinguished son of another Sutton Vane, who had been known in Piccadilly and the Strand as the most prolific writer of popular melodramas of his time. Now behold his son, peddling the script of an odd, elliptical, religious play, unlike any with which the English stage was familiar.

Charon's Skiff—Modern Style

IT is not difficult to picture the average English theatrical manager growing quite red in the neck with laughter about it. Somehow, I seem to see him flourishing his mid-day cigar at the Ivy restaurant and murmuring: "These playwrights! These playwrights! I thought I knew the worst they could do; but, believe it or not, old Vane's son came into my office this morning and wanted me to read a play of his in which—s' help me—all the characters are dead!"

The three scenes of Outward Bound are laid aboard a shrouded craft that is steaming silently from this world to the next. It is a play that looks at heaven, and it was perhaps inevitable that the cathedral hush which its beautiful first performance induced in New York should have been broken by at least one or two shrill yelps of "Blasphemy! Flippancy! Blasphemy!" Here, for once in a generation, a playwright's fancy wistfully renews the immemorial quest into the life that is beyond the reach of most mortal eyes. In a play of extraordinarily engrossing design and substance, he resumes the age-old inquiry into the nature of God and the quality of His mercy. And because there is laughter and irony, and a little human jauntiness, and more than one rueful smile in Outward Bound, certain panic-struck persons set up an ancient mob cry. The same vigilantes would have made short work of that upstart juggler who, in the matchless French legend, did his whole humble repertoire of tricks as an offering to Our Lady. She, as it happened, was well pleased, for She smiled and blessed him.

Perhaps, however, that is not an ancient cry at all, but one you would hear more often and more explicably in this godless age. We have noticed as a curious circumstance that those who make it their special business to rescue the Almighty from the undignified positions into which they find Him forever floundering are always presenting Him as somewhat less likable than grandpa. Indeed, they most often picture Him as touchily requiring the kind of tiptoe obsequiousness which men and women usually accord only to moribund uncles of great wealth and unannounced testamentary intention. They would have us believe that He commands us to love Him—always as dismaying an injunction as that with which the gruesome Miss Havisham chilled poor Pip when, after he had been led trembling into her sepulchral presence, she gazed upon him gloomily and said: "Play, boy." And they picture Him as requiring the kind of awestruck, hat-in-hand demeanor that would have embarrassed grandpa fearfully.

The Goodliest Fere

HIS idea of God is easier to understand in a generation which, in this comer of the world, at least, treats God as it would a spare room; something to be opened only on great occasions. Compared with the lusty and earthy mysteries which enlivened and confirmed the hearty, living faith of the Middle Ages, the rather gallant light-heartedness of Outward Bound seems almost timidly circumspect.

But those rougher and more jocular mysteries were wrought and watched and enjoyed in the days when God was a part of all men's daily thoughts and works. He walked with them in the fields and sat down with them over the bread and cheese and wine at sundown. Close enough to be part of their jokes and their pains, He stood beside them in the days when they cared enough about Him and believed in Him hard enough to fling to the startled stars so unmatched a marvel as the Cathedral which still stands in the town called Chartres.

It is not within the province of these few program notes for Outward Bound to describe with what art and what imagination and what fine instinct its author, and the extraordinary troupe of players it found in America, have, between them, achieved in its three acts a breathless apprehension. You can imagine the dawn of that apprehension in the minds of this motley ship's company—an earnest young clergyman; a high-toned trollop; two frightened, clinging lovers who have committed suicide (stowaways, these); a sardonic wastrel; a good humored and humble little charwoman, anxious to know if her cottage in heaven will "'ave a good sink"; and a complacent merchant prince.

You can imagine the tension of that moment, when it dawns on the wastrel why this ship is sailing with so scant a crew and with never a port or starboard light to warn the tossing sea; and why, too, he had been unable to remember under what circumstances and with what destination in mind he had come aboard. You can imagine the electricity that is astir in the theater when they realize suddenly that the movement has stopped, that the engines are still, that the ship is in port at last.

The Hereafter for First Nighters

ERE they all are, bound now for heaven and hell, in a ship that cannot put back to let any one of them make eleventh hour changes in his luggage—his pitiful little luggage of things done and left undone on earth.

Nor is it possible here to expound Mr. Vane's Book of Revelations, which, as a matter of fact, this recorder found far from nourishing and far from believable. But it should be said that by never a word or gesture, by never a glance out across the footlights, does the author of Outward Bound point a moral or shake a finger of admonition. But in no time the strong suction of the play draws the audience aboard the nameless craft. Each onlooking sinner knows full well that, save for a little extra time in which to consider and perhaps repack that luggage, he, too, is on the boat—sailing with terrible swiftness to he knows not what.

We saw this spell work with the first New York audience which a succession of limousines and taxis had deposited (grand and brimful of food) at the door of the Ritz Theater. Not a bad lot, these first-nighters. To be sure, they are an incorrigibly trivial group of mortals, spending without heed or stint the forty winks allotted to them out of eternity for their visit on this earth. They have just a moment here; but, unlike you and your friends, they spend a lot of that moment in fierce preoccupation with such questions as the conduct of their neighbors, the intricacies of the income tax, and the wisdom of taking a partner out of an original two-bid double. Unlike you and your friends, they devote an incredibly small part of each year to speculation as to how and why they came on earth and what about it.

Mr. Vane's play stopped them short. He came to them with his odd blend of modem tolerance and an ancient piety, and they could not choose but hear. It was the memory of their wide eyes and their silent procession out of the theater when the piece was done which made it at once so exasperating and so amusing an experience to pick up a newspaper next day and learn from its short, severe review that we had all been attending a flippant and blasphemous play.

Continued on page 82

Continued from page 45

Mr. Shaw and the Saints

ONE would rather have expected a similar flu rry to be caused by any play so provoking a fellow as Bernard Shaw might write about the Maid of Orleans; but, after all, Shaw is the least trivial citizen of the British Empire, and his play, Saint Joan, has such sobriety that its performances in New York have been marked by few offended exits. We can imagine playgoers withdrawing because their intellects are unequal to the strain put upon them by his dialectic. We can imagine their departing, "dignified and stately", because they had heard the epilogue was not worth waiting for. But only an occasional fundamentalist leaves in a rage.

There is no dramatic critic over the age of two who could not point out thirty things the matter with Saint Joan. There are more things the matter with it than there are with a dozen lesser pieces along Broadway. But it is a work of genius. It has greatness. Its stature is visible from the moment when the forthright Joan, on being told that it is her imagination which makes her hear her voices in the chimes, replies "Of course, how else does God speak to us evei?" to the moment when, from the Square where the shout of the mob has already bore the tidings of what work the flames have done there, the Executioner of Rouen returns to make his report to the already worried Earl of Warwick.

"Sir," says the complacent Executioner, in a speech of magnificent irony, "you've heard the last of her."

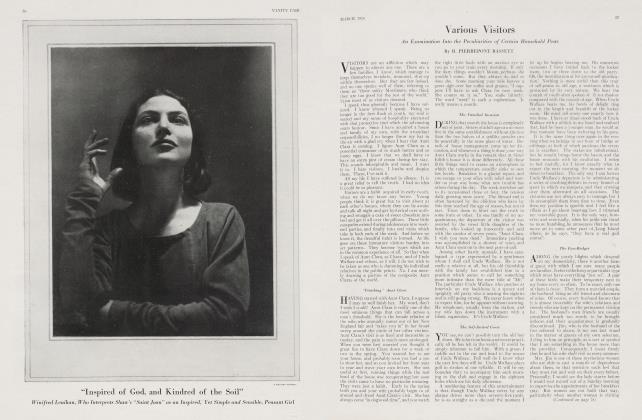

It may be said of Joan, as imagined by Shaw and as embodied now by Winifred Lenihan, that you are persuaded the real Joan was much like that. And it is both the intention,and the effect of the play to assure you that those who opposed her were much like you and your neighbors; to suggest that Joan, were she to return to earth again, would be burned again, while those who can now drop a sentimental tear over her pretty story would be among the first to carry fagots to the Square.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now