Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowArithmetic, as Applied to Auction Bridge

A Review of Some of the Counting Systems that have Come into Use

R. F. FOSTER

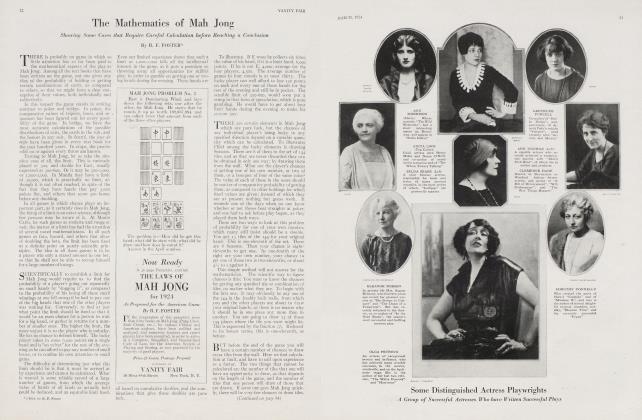

Problem LVII

There are no trumps and Z leads. Y and Z want six tricks. How do they get them? Solution in the April number.

SINCE the earliest days of bridge, long before auction was thought of, good players have felt the want of something to guide them in their estimate of a hand for a bid. In bridge, the first declaration was final, and was good for either side to go game, as there was no opposition from the non-dealer's side. In auction, the first bid is only a starter, but it carries with it quite as much responsibility as the one and only declaration at the older game of bridge.

All bidding is based on naming something in which you probably have an advantage over your opponents. You bid no trumps when you have more than your average share of aces and kings. You bid hearts when you have more than your share of the average distribution, five cards out of thirteen, and at least two honors out of the five.

In both cases there is the element of counting, and the idea of getting this counting down to some kind of a system is as old as the game of bridge. About twenty years ago, Charles S. Street introduced a rule for suit bids which was afterward elaborated by Robertson for no-trumpers, and which is still known as the Robertson rule. Mr. Street's system was to count the number of cards in the trump suit, add the high honors, and count one more for each outside ace or king in plain suits. If the total was eight or more, it was a bid.

J. B. Elwell's rule was to count all the aces, kings, and queens you did not hold as losers, and to make up for them by outside tricks. Thus, five spades to the ace would require two outside tricks for a sound spade call by the dealer.

The general rule in those days for no-trumpers was briefly expressed as "three aces". In my Complete Bridge, published in 1905, I gave the first demonstration that any hand that was a queen above average was the same as three aces, if there were three suits stopped. That is, if a player had A K Q Q J 10 so distributed as to protect three suits, he had as good as three aces. In the same book appeared the first demonstration of the immense advantage of the declarer in playing no-trumpers, showing, on page 57, that with precisely the same cards in all four hands, he could win twice as many tricks as his opponents. This was later worked out in a series of articles in the Rochester Post Express, and ten years later was elaborated by Wilbur C. Whitehead.

THE bridge idea of a queen above average is the foundation of all pip-counting systems. The Robertson rule, which was originally for no-trumpers only, just as Mr. Street's rule was for suit calls only, gave these arbitrary values to the five honors:

These total 18, add the value of a queen, and we get 21, which was the rule for a notrumper, if three suits were stopped. The objection to the Robertson rule has always been its artificial values, and the number of exceptions that must be noted. A singleton ace is worth 4 only; a singleton king, 2, and an unguarded queen, I. Allowance must be made for suit distribution by applying what is called the "seven rule , which combines the number of sure tricks with the number of protected suits. Thus 4 sure tricks and 3 suits guarded count 7. So also 5 sure tricks and 2 suits guarded; or 6 sure tricks in I suit, are all no-trumpers by the seven rule.

It is easy to see that many hands which will fit one rule will not check up to the other. For example, A K Q in one suit, K J in another totals 22 by the first rule; but only 4 in the other. Ernest Bergholt, card editor of the London Field has modernized the Robertson rule to take in suit bids in this way:—

Ill addition to the ordinary count of 7 5 3 2 1, for the honors, add 2 for each card in the proposed trump suit, whether they have been already counted as honors or not. This gives Us 4 times 18, or 72, for the honors, and 26 for the 13 trumps in the pack, total 98. Divide this by the 13 tricks to be played for, and we get, roughly, 7pi as the value of each trick. For a trump call, five in suit being the usual minimum, we get 10 for the trumps, and with ace-king at the top we have 12 more, total 22, which just exceeds the 21 rule for a bid.

THREE years after the Robertson rule was formulated, W. H. Whitfeld, professor of mathematics at Cambridge, and the author of the famous six-card Whitfeld problem, analyzed a large number of deals with a view to checking up his calculations as to the comparative trick-taking value of the five honors. He found in practice that an ace was worth almost as much as two kings, so he advanced the ace in the Robertson scale to 9, leaving the others as they were. In suit calls, he found it necessary to subtract 1 for honors not in sequence, such as A Q, and to add 1 for three or more honors that were in sequence, such as KQJ.

Whitfeld's counting system also laid the foundation for the modern system of bidding two on length in the major suits. He added 1 to the count for six cards headed by three top honors, and added 2 for such suits of seven cards. The defect in his system was that he paid too much attention to lone queens, jacks, and tens; cards which the modern player ignores, except in combination with higher honors.

The advent of the double value of the spade suit destroyed the value of pip-counting systems for a time, because in many hands the dealer's bid did not mean what he said. When the lower value of spades was abolished, and the suits took up their present rank, putting any one of the four within reach of game, pipcounting systems came into favor again. The only difference between these modern systems, of which there are now four or five, and those given by Street, Robertson, and myself twenty years ago, is in the values attached to the high cards.

Bryant McCampbell, the author of Auction Tactics, and the modem champion of the deferred bid, seems to have been the first among recent writers to advocate the pipcounting calls. He calls his method the "Pitch System", giving these values,

He calls II points in three guarded suits a weak no-trumper; 12 a strong no-trumper; 14 a no-trumper on two suits only, a "sporty" no-trumper; while he advises bidding two on three suits that count 16.

ILBUR C. WHITEHEAD'S system first appeared in the N. Y. Sunday Sun January 7, 1917, as a proposition to combine both no-trumpers and suit bids under one scale of measurement. He started with the old theory that a queen above average was a notrumper. If this were true, then a queen above average in any hand should be a bid of some kind unless the distribution was unfavorable. McCampbell had already cut out the ten from the five honors. Whitehead went further and cut out the jack. His values were based on quarter tricks.

This gives us 28 as the total for the four suits in the pack. Taking one-fourth of this as average for each player we get 7, and Whitehead recommended a bid on any hand that was worth 8. This was simply putting the Robertson rule in another form. Three months later he departed from all other counting systems in assigning the same value to each of touching honors, such as the king combined with the ace of the same suit, as either might evidently be played to the trick with the same effective result. This advanced the counting value of high cards that were touching other high cards. Here are two examples:

Continued on page80

Continued from page62

The first might be a no-trumper. but for its being a better spade call. The second is a diamond. Under the Robertson rule the first is not a no-trumper, as it is worth 18 only. The second is a diamond, as the two honors are worth 13 and the five trumps 10, total 23. The first hand would be very strong, counting 28, for a spade under the Robertson rule. Elwell would have counted the first to lose 8 tricks, and the second to lose 10. Bryant McCampbell would get the necessary II on the first; but only 7 on the second.

Whitehead's rule, the truth of which has since been abundantly proved in practice, is that any suit of five cards headed by both ace and king is a bid, although Milton Work refused to admit it for several years, insisting that there should be at least one outside trick. The modern player does not wait for that.

ABOUT ten years ago, R. L. Beecher, a nephew of Henry Ward Beecher, devised a pip-counting system, the chief merit of which was its simplicity. He follows the McCampbell values, but cuts out the jacks, leaving the ace at 4. king 3, and queen 2. This gives us 9 for each suit. Adding the standard queen above average brings the necessary count for a bid up to 11.

The peculiarity of the Beecher system was that every hand was a no-trumper or nothing for the dealer or first bidder. The partner could take it out with a suit if he had any five cards and a count of 8. The weakness of this system was that it forced the dealer to pass up hands as good as seven hearts to the ace king queen, because they did not count 11. On the other hand, no-trump would be bid on an ace-king suit and the ace of another suit, which counts 11.

This system was tried in a set match at the Knickerbocker Whist Club, Mr. Beecher taking E. T. Baker for his partner, against Sydney S. Lenz and his partner. The weakness of this and of probably all pip-counting systems was exposed in this match by the result of several hands; not because the bidding was unsound, but because the system betrayed the holding when no bid was made. Here is one of the deals, which will illustrate the point in a simple way:

AS dealer, Mr. Beecher passed, as his - hand counts 10 only; an ace 4; two kings at 3 each. When both second and third hands passed. Lenz bid no trump. A small heart was led, won by the ace and

returned, the king killing the jack. To show his reentry, before clearing his heart suit. Mr. Beecher led the king of spades.

This lead marks him with the ace, and shows that he held at least 10 points, but he did not hold 11, or he would have made a bid. Then he cannot have in his hand anything else even as good as a jack. This marks the jack of clubs in Mr. Baker's hand, and the finesse of the ten by Lenz wins the game and rubber.

Dr. T. C. Lusk was the first pipcounter to devise a system that changed the values required according to the position of the player at the table. He used the McCampbell values, 4321, and required 11 for an original bid as dealer; 12 for second hand; 14 for third hand and 16 for the fourth hand, after three passes. He also thought 11 points the least that would justify a double.

Personally. I am unable to see that any of these systems, which attach an artificial value to certain cards, and which also require a certain amount of mental dexterity in the processes of addition and subtraction, are to be compared to the simpler way of counting up the sure tricks, and doubling their value for attack. What can be easier than to say the ace and king of a suit are worth two sure tricks: if you play the hand they are worth four, and four is more than your share of the thirteen to be played for, therefore, you should have a bid?

Answer to the February Problem

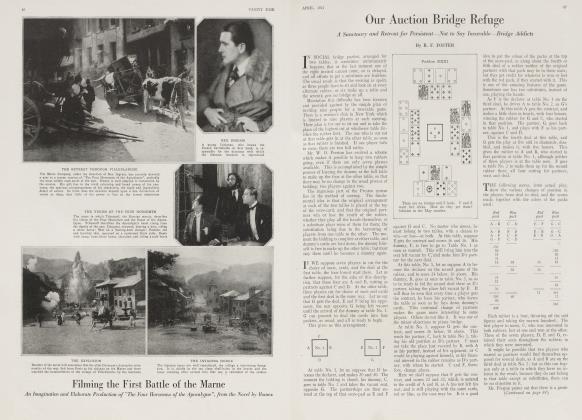

This was the distribution in Problem LVI. which is a fine example of Mankowski's skill as a composer.

Hearts are trumps and Z leads. Y and Z want six tricks. This is how they get them:

Z starts with a club. If A covers, Y trumps with the seven of hearts and leads the spade four. Z wins the spade and leads his remaining club, upon which Y discards the spade queen. Z follows with the winning spade; ace or ten, according to B's play on the first spade lead from Y's hand.

If A discards a club on the winning spade, Y sheds a diamond and makes two of his trumps by undertrumping the next trick with the trey of hearts if A plays one of his high trumps on the next trick. But if A trumps the spade with the eight of hearts, Y over-trumps and leads a diamond, which Z trumps, and the spade comes through A again.

If A trumps the top spade with an honor, and Y discards a diamond, when A leads the club Y trumps with the trey, and Z over-trumps with the five, so as to lead through A again. If A does not cover the first trick, Y sheds the spade queen, trumps the next club with the heart seven, regardless of A's play, and leads the spade four, which Z returns through A. Y's trumping the first trick with the seven is the key.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now