Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Old-Fashioned Menace of the Screen

A Glance Back at 1914, and at the Movies of That Time

VIVIAN SHAW

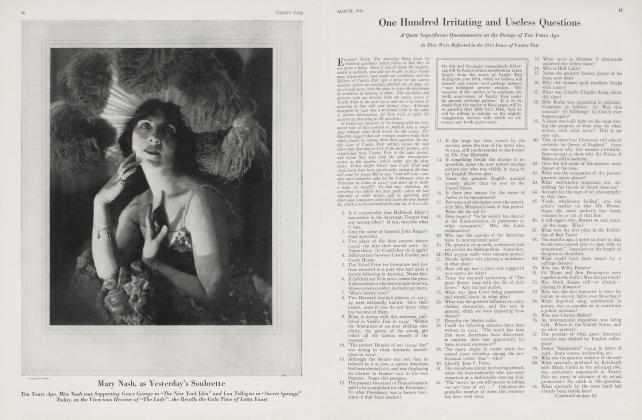

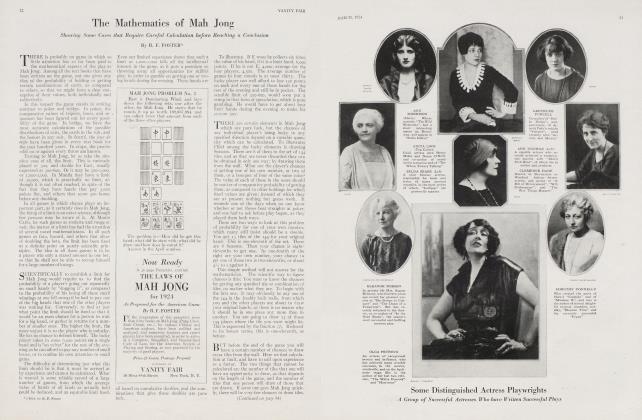

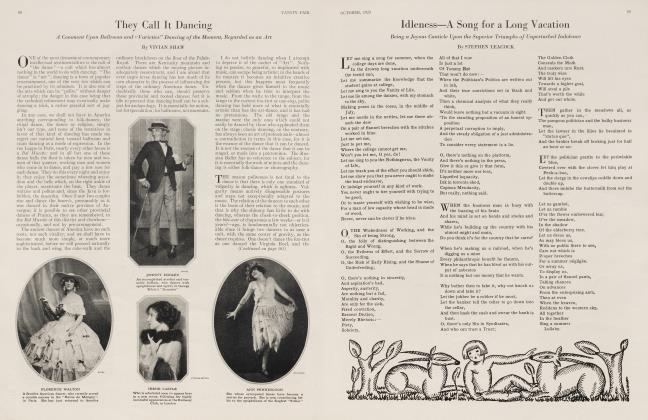

The interesting thing about this picture is that, with two exceptions, all the screen stars shown in it have been entirely creations of the past ten years. In 1914, when Vanity Fair started to give editorial space to motion pictures in America, only two of these stars had been heard of. Those present are, reading from left to right, Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, Norma Talmadge, Richard Barthelmess, Lillian Gish, Baby Peggy, Jackie Coogan, Nita Naldi,

Pola Negri (with fan), Alice Joyce, Alice Terry, Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, George Arliss, Dorothy Gish, William S. Hart, Mae Murray, Lenore Ulric, at back, Ro.dolph Valentino, Tom Mix, (on the horse), Glenn Hunter, and Gloria Swanson, amid a scene compounded of their exploits: stockades and castles, mountains and meadows and forests, windmills and pyramids. The picnic party was given by Vanity Fair, in honor of its tenth birthday

PLACING ourselves back in 1914 and looking prophetically forward, there are striking things to record: growths and changes and disappearances and developments. The greatest of these, obviously, is the change in the character of the patrons, and the change isn't simply that once the movie was the theater for the poor man and the provincial, and now has absorbed some portion of nearly every level of wealth and intelligence.

The audience has, at the same time, grown fastidious in this sense: that ten years ago, every week brought thousands of people to the movie, to whom the thing itself was so much a trick or a game or a novelty that they didn't pay much attention to the particular thing shown. This was the happy time of the serial adventure film, the dime-novel days of the movies. It is a far cry from Nick Carter to those moving accidents by field and flood which are occasionally woven into fine novels, and the moving picture hasn't yet traveled the whole distance, but it is on its way from the Exploits of Elaine to some Odyssean wanderings.

Just as the adventure serial was the counterpart of the romantic spectacle, so the vamp picture was the parallel to the dramatic moving picture which deals with the emotions. This is the hardest job for the pictures, and a glance at the films which are put on for long runs at big theaters and high prices will show that the producers are turning away from it. The Covered Wagon, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, The Ten Commandments, Scaramouche, Orphans of the Storm and a dozen others indicate that the elaborate film, the film which will draw multitudes, must depend on something other than an emotional interest.

This is equally true of stage spectacles: the danger in the case of the movie is that the big film tramples down the little one. So many of these big ones are made that the small picture house which must show the super-features presently will have no time for the smaller, and often better, films. A film about a letter carrier might be expected to be a comedy drama of everyday life, but it is transmogrified into "a giant epic of the screen"; and I give you my solemn word that I saw Eugene O'Neill's Anna Christie announced as the "latest crook drama of the year". Things are forced into categories where they do not belong, on the assumption, a safe one, that people like what they like, and will always continue to like it. BUT one lookingforward from 1914WOUW not have known that the screen would presently absorb the energies of a vast number of stage actors, and would eventually throw them back on the stage. He would not have guessed that the producers would grow sensitive to criticism, would engage competent advisors and men and women of comparatively high standards of taste. I do not allude to the second-rate novelists, who have so large a share in making the pictures vulgar; I mean the more obscure people who have written bright scenarios and engaging captions, prevented absurdities and supplied decent settings, and have occasionally not debauched a fine novel nor sunk to the lowest depths of a bad one. I do not claim that when they are banded together in a Film Guild intelligent people make the best movies. They prove, and it has been necessary to prove it, that intelligence can be applied to the pictures, and that the effort is justified.

Continued on page 76

Continued from page 40

I think that a wise visionary in 1914, having seen The Cmeard. would predict a fine future for Charles Ray—but not the future he has had in his recent withdrawal from dramatic, into comic, parts. Seeing the Fox-Kellerman output about that time, he could have predicted the Fox future to the last foot of lilnv, observ ing Griffith's genre pictures before The Birth of a .Cation, he would have been the la>t to consider Griffith the forthcoming star of the spectacle; with John Bunny and Flora Finch in mind, and forgetful of what was going on under Mack Sennett, he would have said that the comic must remain a pure grotesque.

In 1914. a magazine as awake to the social scene as Vanity Fair had the meagerest references to the films. RuthStonehouse appeared in an advertisement for something in clothes; there was talk of the "songies"—films with opera combined. John Bunny, known as an actor, was rather reproachfully interviewed; a note appeared on the menace of the pictures —not in regard to their moral effect, but with reference to the empty gallery seats at the theater; Griffith was praised by an anonymous actress because he. alone of directors, let the players know what the scenario was about; there was a picture of a foreign actor now forgotten; and an article explained the commonest tricks of the pictures, with diagrams. That is all!

"No Chaplin, " leaps to the mind. No. It was the year of Tillies Fnurtured Romance and of Dough and Dynamite, Laughing Gas, Caught in a Cabaret, and so forth; but Charlie was not even a figure of fun in those days. And no Pickford. No; in those days, they were just beginning to announce the names of players; it was still possible to see films without a cast of characters. And in those days, too, they were not making good pictures, except at the hands of the Fine Arts. Paramount and Famous Players were positive learners at the game; there were others who were refusing to learn.

For whatever the faults of the billiondollar, stupid movie may be, it has helped to create the almost perfect mechanism which we now possess. It has made available for other hands an instrument utterly unpredictable ten years ago. And even if it has spoiled public taste, it has seen to it that there is a public. In ten years, the movie as we know it, was created; in the last five, it was very nearly ruined; but the greatest thing about it is that it still exists, and is about ready to be taken over bv those who care for it.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now