Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Golfer Who Changed His Style

BERNARD DARWIN

A Speculation Upon the Possibilities of Fluctuation, from Time, to Time, in a Player's Characteristic Manner

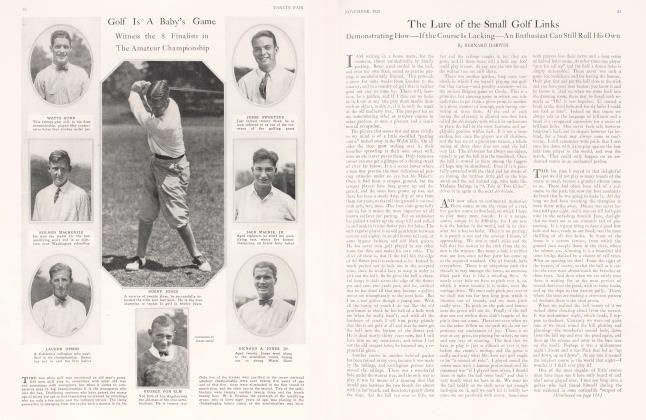

HOW many golfers do you know who have changed their styles? Of course, you can think, and I can think, of hundreds who say they have done so. They say it every time they do a good score, and imagine themselves to have found the eternal secret. We say it ourselves, but what do our friends say? They, I am afraid, see no difference at all. When they see us silhouetted against the sky-line, they exclaim, "There's old so-and-so. You could tell him a mile away."

Personally, I can remember in a fairly long experience just one, or perhaps I may allow myself, two golfers who have really and truly changed their styles. I have very good cause to remember one of them. Some two or three years ago, he was by no means a bad player, but he had one serious fault. At the top of his swing, his right elbow rose mountains high in the air, so that he looked like one of the golfers shown in woodcuts in prehistoric manuals of the game. Being a very painstaking person, he went to a golf school, and wrestled in prayer with his fault.

When next I saw him, it was in a tournament, and he was a changed man. He kept that elbow tucked in to his side by sheer force of character. One could see the elbow struggling to be free, and my friend with set teeth keeping it down; and ever and anon as he walked between the strokes, he would slyly practice swinging an imaginary club, looking sternly at his elbow the while. He played very well in that tournament, and I endeavoured to say so in my report of it.

The Case of Mr. Woolley

I WAS an innocent creature, with no thought of a double entendre, for I wrote: "Mr.H. is now a very good golfer, having conquered the habit of lifting his elbow." Poor H. is a member of the Stock Exchange, where they are fond of ribald jokes; and when he turned up there next day he was greeted by a huge cartoon of himself, depicted with his elbow tied down to his side, trying vainly to reach a large whisky and soda, held temptingly just out of his reach. It is evidence of his forgiving character that he and I are still friends. However, the laugh is entirely with him, for in his new style he has won a championship that needs a good deal of winning.

My second instance is that of another very good player, Mr. F. A. Woolley, who would certainly have played in one of our Walker Cup sides against America, if illness had not cruelly laid him by the heels. I first saw him play when he was a schoolboy of sixteen or so. He then had the typical boy's style of "bombastic freedom", exaggerated to the uttermost point, so that the club dangled round his toes at the top ot his swing. I did not meet him again till he was a young man of four or five and twenty, and chosen to play for England against Scotland. Then he had the shortest swing that I ever saw in a first class player. He took the club no further back than most people do in playing a short mashie shot, and thrust it through and after the ball with the most tremendous follow-through imaginable. I asked him how he had so completely revolutionized his swing, and he could only say that, as far as he knew, the change had come naturally and unconsciously when he adopted the overlapping grip.

Apart from these two examples, I cannot recall any golfer who has changed his style to outward appearance. A man may put his feet in rather different places at different times; he may swing just a little longer or shorter, faster or slower; but he looks essentially the same. The Ethiopian cannot change his swing, any more than he can his skin. I do not mean to be depressing when I say this. The poor Ethiopian may enormously improve his methods, even though the general impression he produces on the unobservant eye be exactly what it always was. It is not merely the swinging of the club that makes us know our friend on the dim horizon. It is his whole air, made up of a hundred little tricks and mannerisms.

Marks of Identificatication

I KNOW you by the waggling of your "head" says Ursula to Antonio, in Much Ado About Nothing; and it is a most discriminating remark from a golfing point of view. It is the way in which he looks at the line, takes up his stand and waggles his club that makes us know our friend, quite as much as his actual swing. We are ready to swear to him long before he strikes, and so have a pieconceived notion of how he is going to swing the club.

It gives one just a little bit 0/ a shock nowadays to come suddenly across a photograph of Harry Vardon as he was when he reigned supreme and peerless in the gutty days. For one thing, he was a great deal slimmer than he is now. Andrew Kirkaldy used to call him the "greyhound", which would not today be so appropriate. For another, he swung the club much further; he swung it an appreciable distance past the horizontal. For a third point, he has to some extent cut out that wonderfully timed sway of the body on the back swing. To use a phrase which is, I think. George Duncan's, he now takes up rather less room in making the swing than when he was younger.

Yet, the fact remains that if I go out and watch him tomorrow, he will appear to me exactly the same Vardon whom I first saw at Gan ton, in 1896, just after his first championship victory. There will be the same perfect rhythm and footwork, the same indefinable characteristic little lift in the back swing, the same stereotyped graceful finish, time after time. Or at least, they will seem the same to me.

The Danger of "Swaying"

I FANCY it must be a sign of age to curtail the sway of the body. We are rightly warned in the text books against the awful danger of swaying, and yet some very great players have swayed, palpably, though with perfect art. But as they get older, they either deliberately or unconsciously lose a little of it. Ray certainly does not throw his weight as far back on to his right foot as he once did; neither, of course, is there so big a corresponding lurch on to the left, as he hits. Herd, again, is another who, at the age of 54, has curbed his juvenile exuberance.

At one time, if you stood opposite Herd as he was driving, and carefully watched a tree or a telegraph post in line with his head, you could see how far his head moved away from its original position on the back swing. It gave one a positively uncomfortable sensation, like that of watching the horizon go up, up, and up. or down, down, down, on board a rolling ship. Today, though Sandy still lashes at the ball with the ferocity ot' perennial youth, most of that sway has gone. But in a broad, general sense, there is no change. Nobody who is not blind or idiotic could doubt for a moment that it was the same Sandy.

Taylor, again, is still Taylor, though his stand is far more "square" today than when he first burst on the world, flicking brassy shots up to the pin like mashie shots.

Mr. John Ball, in his youthful days, had a noticeably wide straddle, and played with the ball very far back, almost opposite his right foot. Today, the years have so far tamed him that he has his feet fairly close together, and the ball in a more orthodox position, only a little behind the left heel. But it does not need the button-hole of great occasion, nor the stockings with red tops, nor that unmistakable walk with the bent knee, to make one exclaim delightedly as one looks out of the window at Hoylake, "There's John!". The essential beauty of the swing is unique and unchanged, just as unchanged as is, alas! the essential ugliness of our own swings, even on those days to be marked by a white stone, on which we fancy we have "got it right at last".

A Distinguished Amateur

I OUGHT not to leave out one modern instance of a change of a somewhat different order. That is in the case of Mr. H. D. Gillies, whom some American golfers have met in England; a very fine and ingenious player, and incidentally,a surgeon who has made a world-wide reputation by his wonderful facial surgery during the war. He has now, for some little time past, been flabbergasting the orthodox here, and possibly some rumour of his heresy has even crossed the Atlantic. He has taken to playing his tee shots with a club having a face 2 1/2 inches deep, off a Lee varying from three to fifteen inches in height. His tee consists of a stick, with a spike at the bottom to fix it into the ground. The upper part of it is clothed in india rubber tubing, and on the summit of the tubing sits the ball. The idea is that of hitting the ball away with a flat, sweeping movement, such as we employ when the ball lies rather "above us" on a bank; and whether or not it is a sound one, Mr. Gillies certainly drives with great accuracy and power from the top of his preposterous tower. But the curious thing is that, though he may have changed the face of the whole game of golf, he has not changed himself in the least; he remains simply "Giles", as he is affectionately called, hitting off a high tee.

I have been trying to think whether any American player has, in my eyes, appreciably changed his style. There is one who has, I think, to some extent, and that is Mr. Evans. If I try to conjure up a vision of him as he appeared at Prestwick, in 1911, there does seem a difference. He almost certainly has a shorter swing today than he had then; but there is something more. In that ruthless search after simplicity and accuracy, he has taken something of the old, graceful roundness out of his swing with wooden clubs, and makes them look more like irons. Very likely, it has profited him. Heaven knows, he is good enough, and I suppose there is no one in the whole world of golf who makes so few bad shots. Yet I confess to sighing a little after the earlier manner, with the springtime and the bloom of youth.

(Continued on page 100)

(Continued from page 77)

It is a fortunate circumstance that, though we see and say that the styles of all our acquaintances are practically immutable, we do not in our heart of hearts believe it about our own. We feel so entirely different on the day of our latest discovery that we must surely look different to anyone who has eyes to see. If once we lose this beautiful and childlike belief, the game is up. There will be no more golfing cakes and ale, no more fun in theorizing. And I fancy that this little kink in our brains is on the whole good for our golf, from a practical point of view. The mental image that we have of ourselves can be very helpful. Only the other day, to give an egotistical example, I was playing uncommonly ill, and a tournament began on the following morning. When my partner and I had lost our match by 6. and 5., and only the bye remained for experimental purposes, I said fiercely to myself, "Well, if you can't hit the ball like a golfer, at any rate, try to look like a golfer when you are missing it!" For those last five holes, I imagined myself looking like the most graceful and finished player I could think of. I will spare my own blushes and conceal the name of the particular champion. The effect was truly remarkable, for I began to hit the ball; I went on hitting it —more or less—for three days, still reveling in my vain and fantastic dream; and, to the open-mouthed surprise of myself and everyone else, I won!

Of course, my friends could not see any difference, and I knew they couldn't, for there was not one to see; but my power of make-believe lasted just long enough to pull me through.

Our lunatic asylums are largely populated, as I suppose, by people playing games of this sort by themselves. They imagine themselves to be Napoleon Bonaparte, or Julius Caesar, or George Washington, and are perfectly happy in their assumption of the part, keeping their pity, not for themselves, but for the poor, sane creatures, who can not recognize them. Well, pe-haps a little mild, harmless lunacy may be a good thing for our golf!

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now