Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTwo Interesting Figures in British Public Life

Austen Chamberlain and Lord Curzon Come under the Critic's Scalpel

PHILIP GUEDALLA

THE RIGHT HONOURABLE AUSTEN CHAMBERLAIN, M. P.

Noted Son of a Notable Father

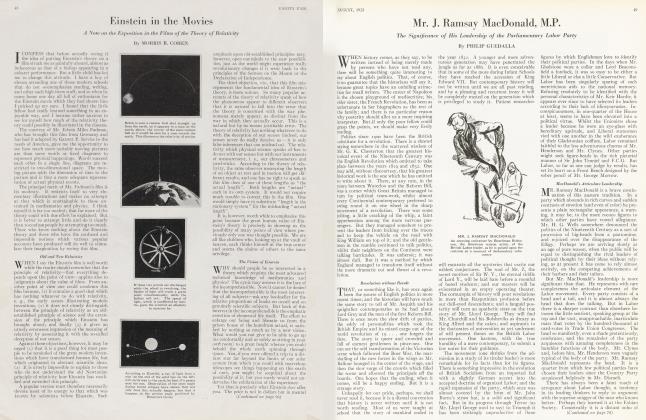

MR, PITT was the son of Lord Chatham; Dumas fils was the son of Dumas père; and Mr. Austen Chamberlain is the son of Mr. Chamberlain. The fact of his paternity, although it is almost sixty years old, is still the most significant thing about him. Without it, he might never have worn an eyeglass; and without an eyeglass he could hardly, one fears, have found the way to Downing Street. For the great majority of his countrymen, the elderly gentleman who filled an honoured position as Lord Privy Seal and leader of the Conservative (and, in its more traditional moments, Unionist) Party, is still the son of the Member for West Birmingham. They seem to catch the patter of his little feet down the long corridors of Highbury, to watch the gleam of an orchid, the glint of a distant eyeglass, as a lean hand runs through his long curls and the little fellow looks up into an angular face.

POSTERITY has an awkward way with the IF sons of great men. The public intelligence is slow to move, and it clings closely to the one fact which it knows about them. They will always remain, as the colour fades from their hair and the lines come round their eyes, the little sons of Mr. X. British Opinion, having mastered their fathers' name, sinks back exhausted by the effort. It will retain it for a generation or so; and, whenever it catches sight of a member of the family, it will murmur the patronymic in a reminiscent way. The encounter gives pleasure, because we love to be reminded of the few things we know; and the old names stir an endearing swarm of memories. There is a pleasant rush of old stories and old cliches to the public mind, as a surviving son reminds it of the hats He used to wrear, His familiar flower, and His dogs. There is a sharp rise in reminiscences, as the younger generation appears, trailing clouds of someone else's glory.

This peculiar privilege affects its wearers in two ways. They may be truculent and insist upon their right to walk alone. They may be docile and answer to their father's name; and then a mild career is open to them as sons, nephews, grandsons of the great man. Yet, even so, their genealogy sets a rigid limit to their flight. The name they bear will start them on the road; but halfway to greatness it will hold them back, because the English do not expect too much of people's sons. It was indelicate in Mr. Pitt to go quite as far as his father had gone; and his career remains an isolated, a somewhat melancholy warning to the sons of great men who have ideas above their station.

Something of this tendency has stereotyped a youthful image of Mr. Austen Chamberlain in the public mind. He is always, perhaps he will always be a young member stammering creditably through a maiden speech thirty years ago. He has travelled a long road since 1892. But, for all the Budgets that he has introduced and the political ventures in which he has been involved, one will always see him as a young man with a smooth head wearing his father's eyeglass. When he makes a public address, one looks for a tight-lipped father sitting proudly to watch his son's performance; and when he sits down, one half expects a gracious, deepvoiced old man with a tea-rose in his coat (and Mrs. Gladstone somewhere handy behind the Grille) to compliment the father on his promising son. Yet that was thirty years ago, and the young man with the smooth head was, for a time, leader of the party which his father never wholly captured.

The predominance of his father, Joseph Chamberlain, that sharp-nosed figure in British politics after the withdrawal of Mr. Gladstone was remarkable and complete. He had set out with every disadvantage—with no father to speak of, an address in the provinces, and an awkward doubt as to the soundness of his views on the Monarchy. Across the luxuriant landscape of the late Disraelian scene he travelled, a bleak little figure in broadcloth. It was known that he earnad his living; it was suspected that he manufactured hardware; and it was believed that he regarded the throne of Queen Victoria with a fierce republican eye. By a touch of the grotesque, he was a provincial Mayor; and, with a final lapse of taste, he elected to reside in Birmingham. The demerits were obvious; and yet, when a sensitive critic visited a musichall forty years later, an entertainer said, "I will now present to your attention a gentleman who is known to all of you." There was an uneasy stir among the assembled subjects of King Edward. We thought of winning jockeys, of aeroplanists, of foreign Ministers, and of His Majesty the King. The entertainer turned suddenly round and presented us with a cockedup nose, an eyeglass, and an orchid. And from the very places whence there had burst forth an applause of Lloyd George so loud that we had imagined it could not have been surpassed— from those very upper parts of the house there burst forth cries, howls, stamping of feet—a noise of enthusiasm such as reduced the approbation of Mr. Lloyd George to a faint platonic sound.

MR. BALFOUR, Mr. Asquith, even Lord Salisbury, might walk unnoticed down the street; but a fur collar and an eyeglass sufficed to collect a crowd and draw a cheer. Mr. Chamberlain left his son as a legacy to the British people; and in a sense they have erected him as a monument to his father. All that they ask (and, if malice is to be believed, nearly all that they get) is an eyeglass and a familiar look. It is, for Mr. Austen Chamberlain, a hard (and yet an easy) fate.

His qualities can never be judged on their own merits. When he is shrewd, it is his father's shrewdness. When he shows character (and at the India Office he once gave an honourable display of it), it is the father's character. His name, it would seem, ensured him a position. But having raised him to it, his name quite firmly held him oack from rising higher, kept him, as it were, at a respectable height of secondary eminence befitting an hereditary office holder. It is an unkind destiny, which must console men whose maiden speeches are not made to listening fathers on Front Benches or acclaimed by old friends of the family at the despatch box.

THE RIGHT HONOURABLE MARQUESS CURZON OF KEDLESTON, K. G.

An Exponent of the Grand Manner in Politics

A SKILFUL observer, whose contributions to contemporary biography have made her more readers than friends, saw him as a young man with "appearance more than looks, a keen, lively face, and an expression of enamelled self-assurance." Most of the liveliness, perhaps, has faded; but the rest remains. Yet the manner which is tolerable in an ex-Viceroy of India must have been singularly exasperating in a young man from Ball iol with no claim to distinction beyond the commendation of the Master, a Fellowship of All Souls', and the Presidency of the Union. One is hardly surprised that contemporaries wrote wicked rhymes about him; and an inheritance of that vague resentment of that pardonable tendency to deride the grand airs of someone who had not yet done anything to justify them, seems to have lingered into our own time. There is always an inclination to think of his manner before his achievement, and one is conscious of a temptation to chalk irreverent things on that broad, averted back. Such treatment may have done well enough in 1895, when he was»a faintly irritating paragon among Under-Secretaries. But it is hardly adequate in a generation which has sent him to India—and even to Lausanne.

In his early phases he climbed the lower slopes, supported mainly by a belief in his abilities. "He had," if the feminine observer is to be believed, "ambition and—what he claimed for himself in a brilliant description—'middleclass method'; and he added to a kindly feeling for other people a warm corner for himself . . . George Curzon would outstrip his rivals. He had two incalculable advantages over them: he was chronically industrious and self-sufficing; and, though Oriental in his ideas of colour and ceremony, with a poor sense of proportion and a childish love of fine people, he was never self-indulgent. He neither ate, drank, nor smoked too much, and left nothing to chance." It was a sound equipment.

One is hardly surprised that this admirable, if distinctly orthodox, Crichton ascended by the regular route. In the days when Lord Salisbury, alone, seemed to stand between Great Britain and the Red menace of Mr. Gladstone, George Curzon threw himself with ardour into the absorbing calling of being a Rising Young Man. He spoke; he wrote; he even worked. By a device which rarely fails at Westminster, he won political esteem by mastering a distant subject; and Turkestan completed the career which Ball iol had begun. The Private Secretary became an Under-Secretary; and the seals of a Secretary of State dangled gleaming in a future which seemed not far distant. Perhaps (who knows?) one might climb still higher; and in the bright dawn of 1891, when Wilde informed a respectful breakfast party in Paris that he was writing a play in French, the obliging young man offered to attend the first night as Prime Minister.

Continued on page 96

Continued front page 39

But there is one feature of those early years which always seems strange to a later generation. One takes for granted the majestic, inevitable procession of his promotion. Two generations have grown accustomed to a grave vision of Lord Curzon rotating easily in a world of red boxes. Official preferment is his native air and the grave formulae of official statements form his normal idiom. But patient research disinters from old diaries an earlier, more frivolous incarnation of the stately figure that brought home to England the solemnity of the East and revived in Lausanne old echoes of a style which had not been heard there since Mr. Gibbon left for home. "George Curzon" (one is always stumbling on the same startling praise) "was, as usual, the most brilliant, he never flags for an instant either in speech or repartee." Posterity is a little apt to rub its eyes. But Mr. Wilfrid Blunt's young men and the self-conscious Graces of "the Souls" knew George Curzon as "a first-rate host and boon companion." The evidence exists; there is documentary authority, which cannot be disputed, for

" . . . a lay Of that Company gay Compounded of gallants and graces,

Who gathered to dine,

In the year '89,

In a haunt that in Hamilton Place is."

One might reasonably credit Lord Curzon with a dignified Muse addicted to slow moving metres and translations from dead languages. But posterity cannot observe her without a sensation of mild alarm, as she cocks her bay leaves over one eye and hurries an unaccustomed foot into the debonair and dactylic measure of—

"Here a trio we meet,

Whom you never will beat,

Tho' wide you may wander and far go; From what wonderful art Of that Gallant Old Bart.

Sprang Charty and Lucy and Margot?

"To Lucy he gave The wiles that enslave,

Heart and tongue of an angel to Charty; To Margot the wit And the wielding of it,

That make her the joy of a party."

It all seems, to the modern eye, extremely odd, and oddest of all that vers de societe should stream from the pen of Lord Curzon, while mots poured lightly from his lips.

As a public figure he has always displayed to perfection that quality of grandeur which Matthew Arnold so admired in epic poets.

There has been a lack, in Lord Curzon's career, of relief. His progress from the perfection of Balliol to the perfection of Westminster, from majesty at Simla to majesty on the red benches of the House of Lords, has been just a thought too regular. He has lacked vicissitudes; and his career, with its persistent upward movement in public office and in Debrett, shows something of the wearisome regularity of the prize boy. His enemies have sometimes confused the Grand Manner with the solemn dignity of an upper servant; and even his friends have not always interpreted his actions fairly. But even if it were true that Lord Curzon is a mere gesture of exclusiveness, there would still be room for gratitude to a public man who walks through public life like a minuet, instead of shambling through it like a one-step.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now