Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

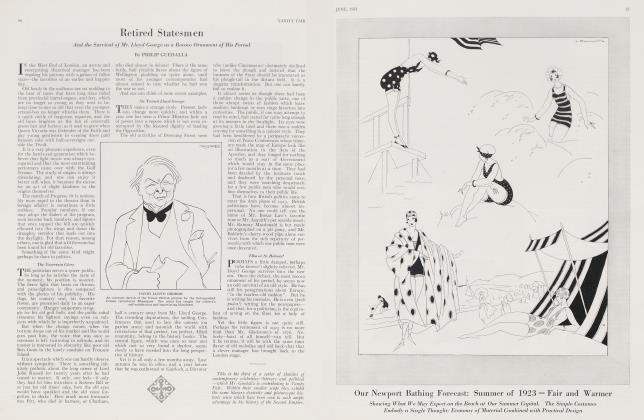

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowWinston Churchill: Is it the Nelson or the Mussolini Touch?

The Dolorous Case of a Wartime Ecstasy that has Ended in Fascism

PHILIP GUEDALLA

HIGH up on the short waiting-list of England's Mussolinis, one finds the name of Winston Spencer Churchill. For those who can still remember his father, its presence there is a bitter comment upon the logical conclusion of Tory Democracy. For those who can remember his own earlier career, it is a crushing repartee upon himself. It is the depressing destiny of almost every Liberal to be, at some stage, the rising hope of the stern, unbending Tories. But it is just as well, if one may venture to advise young politicians, to get it over early. These infantile complaints cause no anxiety in the nursery. The baby's croup is as harmless as Mr. Gladstone's early Conservatism. But when the symptoms appear in an older patient, one fears a graver issue. That is precisely the sad case of Mr. Churchill.

Opening with a fine democratic flourish, he seems to have declined in middle age upon reaction. It is not easy to think of Mr. Churchill as middle-aged; but so, alas! he is. It must be nearly forty years now since Lord Randolph wrote to his wife from Naples: "Give Winston the enclosed Mexican stamp": perhaps it set the young mind running on political violence and ruthless Presidents. And it is certainly thirty since he startled his parents at the seaside by "a miraculous escape from being smashed to pieces, as he fell thirty feet off a bridge over a chine, from which he tried to leap to the bough of a tree".

In his fiftieth year, Mr. Churchill is an old, almost an Elder Statesman. Allowances can always be made for early indiscretions. But wild oats in public (if not in private) life are rarely sown after the fortieth birthday; and one may be pardoned for regarding his present as his final attitude. It is not ignoble; it is far from destitute of rich rhetorical possibilities; and he has, for the moment, sacrificed a fine career to it. But one cannot observe without a quiet sadness this eloquent victim of strictly Conservative delusions.

A Frantic Delusion

MR. Churchill (the symptoms have been apparent for some time) is seeing Red. That attractive primary color has often exercised a peculiar influence upon less sensitive intelligences. Bulls are alarmed by it; mild persons of progressive views derive a sharp satisfaction from irradiating themselves with its wicked light; but its most remarkable effects may be observed in those of the opposite opinion. It takes them like a fever. The eye becomes wild; the speech grows incoherent; references to the Third (and even to the Fourth and Fifth) International begin to appear; frequent quotations from Lord Tennyson on the subject of "Red ruin and the breaking up of laws" afflict the sufferer; and his waking vision is haunted by a constant hallucination of sinister little figures lurking in corners, with foreign accents and inexhaustible supplies of dangerous pamphlets.

The patient becomes practically unapproachable upon all economic topics and sends, on the slightest provocation, for the police. It is a distressing malady, for which no cure is known, except a complete rest. Unintentionally, perhaps, Mr. Churchill has taken the steps which were required to assure his own recovery.

He was almost bound, as one can see now, to fall a victim to this strange infection. Other men have seen little in politics beyond the dreary machinery for the transaction of public business. But he has always dramatized them; he seemed to regard them as an intensely thrilling scenario, with at least one strong part. Politics, in his lively hands, almost became like a political novel; and he has always inclined to that inimitable view of their thrill and mystery, which is presented so picturesquely by Mr. William Le Queux. One can never forget the hissing whisper in which he has described the commonplace operations of Sir Edward Grey and his official subordinates: "A sentence in a despatch, an observation by an ambassador, a cryptic phrase in a Parliament seemed sufficient to adjust, from day to day, the balance of the prodigious structure. Words counted, and even whispers. A nod could be made to tell."

The Dramatic Touch in Statesmanship

THAT is the authentic idiom in which our old friends, Baron X. and Monsieur V., used to recount their invaluable services to their royal master, the King of Krupenia, while on a secret mission at the Court of M. in 189—. One feels that the words were written insympathetic ink, or at least traced in a feigned handwriting, or spoken slowly to an eager listener in the sunshine outside the Cafe B.y long years after the terrible events which shook the throne of King Ladislas and his exquisite consort. Can it be doubted that a statesman, who carried such a view of events from melodrama into real life, would dramatize his politics?

That dramatic instinct, which is Mr. Churchill's strength as a historian, is the source of his weakness as a politican. One can hardly be too grateful for his lively presentation of the dreary minutice of naval history. Gunnery grows wildly thrilling under his vivid touch; Lord Jellicoe becomes almost interesting; and there is nothing better in dramatic writing than von Spee's discovery of the battle cruisers at the Falkland Islands: "A few minutes later a terrible apparition broke upon German eyes. Rising from behind the promontory, sharply visible in the clear air, were a pair of tripod masts. One glance was enough. They meant certain death. The day was beautifully fine, and from the tops the horizon extended thirty or forty miles in every direction. There was no hope for victory. There was no chance of escape. A month before, another Admiral and his sailors had suffered a similar experience."

That, in the historian, is well enough. But when it strays into the field of action, one watches with a faint misgiving. Mr. Churchill, hurrying to Sidney Street to cheer the Guards in their intrepid attack upon two malefactors, with the approving presence of the Home Secretary, may be a harmless prank. But Mr. Churchill in Whitehall, dramatizing the Admiralty with a large chart in a closed case on the wall behind him, showing—this was in 1916—the daily movements of the German fleet; Mr. Churchill, making it "a rule to look at my chart once every day when I first entered my room ... less to keep myself informed . . . than in order to inculcate in myself and those working with me a sense of the ever-present danger"; Mr. Churchill, thrilling the Staff by asking them "from time to time, unexpectedly, 'What happens if war with Germany begins today?"'—these little, prancing figures are more alarming. As the slow darkness deepened across Europe, the actor seemed to get the last ounce out of his part, and when he marched across to Downing Street to report that the war telegram had gone out to all ships, one somehow feels no surprise that a sharp-eyed lady at the foot of the stairs saw him "with a happy face striding towards the double doors of the Cabinet room".

Perhaps it is always easy to dramatize national defense. A signature on a minutesheet in Whitehall, which sets guns booming beyond Cape Horn, would thrill an Undersecretary. Indeed, the whole sea service appeared to take up its duties with a strange hysteria; Lord Fisher set an odd tone of apocalyptic ecstasy in high places, and a quiet Admiral once caught his Minister by the sleeve after a conference with Beatty with the queer ejaculation, "First Lord, I wish to speak to you in private—Nelson has come again." So it is hardly to be wondered at that Mr. Churchill lived in his splendid drama.

War Ecstasy and Fascism

BUT when he transferred its lurid colors, its simple situations, its sudden turns, its villains and heroes, to the more sordid background of domestic politics, the results were less satisfactory. He seemed to attempt transpontine attitudes in a dull play by Mr. Galsworthy. The Red replaced the German peril; and his old fire supported the vigorous artiste through an act or so.

However, there was a total loss of contact with reality. Indeed, one seems to see him, in a distant future, marching black-shirted upon Buckingham Palace with a victorious army of genteel, but bellicose, persons.—What a future for a Boanerges of the Budget League!

Years ago his father told a private secretary that he would take care to educate his son along the lines of Mr. W. H. Smith, and then he would be sure of success. The resemblance to Mr. Smith is barely apparent; but neither, until English Fascismo finds its predestined leader, is the success.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now