Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowJohn Galsworthy and the English Drama

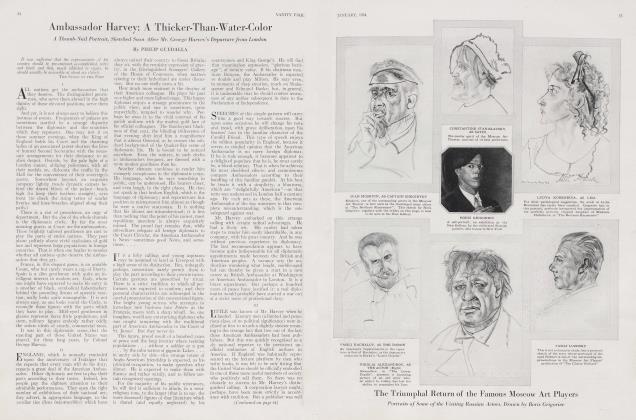

A Polite Depreciation of This Versatile British Writer, by a Brilliant English Journalist

PHILIP GUEDALLA

YEARS ago, when England walked by the mild illumination of King Edward's cigar, and the streets of his capital were a pleasant welter of horse-drawn vehicles and their new mechanical substitutes, the national intelligence was seriously exercised over the state of the national drama. It has been subject to these gusts of solemnity upon subjects to which solemnity is inappropriate ever since the discovery, by those responsible for the conduct of newspapers, that ideas form a useful substitute for news in the holiday season. There followed a pleasant trickle of discussion, which interrupted the quiet tedium of boating accidents and deciduous mountaineers, so seasonable and yet so monotonous in the newspapers of an English August. The mild debate drifted from the giant sea-serpent to the giant gooseberry, and from the giant gooseberry to the Modern Woman; and so, in the first years of the present century, to the New Drama.

They were all writing hard about it in the days of the early motor races, when fainting automobilists drove precariously from Paris to Bordeaux in several days, and their despairing competitors plunged impulsively into the cheering multitudes which lined the road to watch the dust go by. The topic has an exquisite, faded air of the Edwardian scene, of the bland Premiership of Mr. Balfour, of the fiery apostolate of Mr. Lloyd George. One catches a faint echo drifting down the wind from quiet days when the cinema was impressively displayed as a new marvel of science to respectful audiences in music halls, and the Georgians were still in that horrid nursery of theirs, from which they should not yet, should never have been, permitted to come downstairs into the drawing-room. And yet, it is hardly fair to stare too hard at the faded colours of what once was bright. New College, even the New Theatre, was new once. And so, ever so long ago, was the New Drama.

IT was a brave business in those distant days. The dark forces which controlled the British theatre (and its directors have always, if one may believe its more earnest critics, favoured a darkish shade) were to be challenged by the bright young things whose appeal was to the Few. Young Mr. Shaw, younger Mr. Galsworthy, and younger, still younger Mr. Granville Barker, shouldered their pens and marched gravely into battle.

The proud banner of the Intelligentsia was raised in Sloane Square. If the assault could not be carried into the heart of the West End, their drums should, at any rate, be heard beating within a reasonably short subway ride from it; and the Court Theatre became a sanctuary where New Dramatists of competing earnestness, but undoubted novelty, carried, as they loved to say, the torch. And by the novel practice of printing their plays, they enabled those backward members of the public, who would not run so far, to read.

The whole effort was a gallant endeavour to divert the British drama from its normal channels; to distract the attention of the playgoer from his favourite spectacle of a blonde, dishevelled wife returning at the fall of the curtain to a much-enduring husband, after a second act spent in the more enlivening society of another gentleman.

These three figures had become the mathematical basis of British drama. There were other names on the program, of course; a maid or so laid out an opera cloak for the erring wife; a few guests stood round uneasily (in dress shirts) while she hesitated (in evening dress) on the brink of her error. But there were only three real people in the play that counted; and the sole dramatic unity which England respected was a triunity.

Sometimes the actor-manager played the husband; and then his grave features were softly lit up by a red glow from the electric light bulbs in the fireplace, as he laid aside his book and turned to stroke the blonde leading lady on her dishevelled head, when she crouched beside his big armchair to wait, the two of them together, for the slow coming of old age and the still slower fall of the curtain. Sometimes (when there was to be an act of unusual abnegation, a rare poignancy of renunciation, a slow walk up the stage, with dragging footsteps, and out into the darkness beyond the bookcase full of dummy books) he played the lover. Or sometimes the three figures gyrated a shade quicker: their rooms contained a delicious multiplicity of doors, and the piece was understood to have been adapted from the French. But there was never a variation in the mathematical formula, in the commuting and permuting Three, until the faint, far trumpets of the New Drama sounded thinly across London from the Court Theatre.

Their quaint notion was to adulterate the limpid flow of British drama by a sudden infiltration of ideas. For the first time in centuries, some tea was to be put in the dramatic teapot with the water; and perhaps there would not be quite so many lumps of sugar in the cup. Ideas were a strange ingredient for an English play, and the intrepid men who were to manipulate them were largely strangers to the English theatre. There was Mr. Shaw, who could state a case; and Mr. Barker, who could write a play; and Mr. Galsworthy, who almost alone among them could do both. He wrote, happily he still writes, an abundance of plays; but from the first, he has continued to state the same case. It was in the beginning, and it has remained almost throughout his dramatic career, the case which is known to the Police Court missionary as the Hard Case.

MR. GALSWORTHY, as dramatist, has dealt almost exclusively in those cruel exceptions whose suffering proves the rule. If he permits justice to intrude on his stage, it is in the form of a miscarriage of justice. If he tolerates an accident, one may be sure that it is a particularly wanton accident. If there is any luck going, it will be bad luck. His point of view, as a dramatist, from the days of The Silver Box to the days—unnumbered, one hopes— of Loyalties, is an extension, a projection upon the stage of the faintly oppressive humanitarianism which haunts his earlier writings. He seems to pity humanity, with the mild monotony of a figure in a Pieta. He regards life rather as a retired inspector of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children must regard parents. The sight of a butterfly makes him think of wheels; and he can hardly bear to look at a fly without remembering the cruel, cruel amber.

IT is one point of view, like another; and Mr. A Galsworthy has embalmed it in an admirable series of plays. Haunted by the cruelty of life, he tends sometimes to specialize in the sort of people to whom life is always cruel; in that concave type which appears to have been designed to meet the impact of disaster; in those shadowy figures who seem to wait, effaced in their little corners, for the inquest and the coroner. The faintly ineffectual charwoman who flits across the tragedy of The Silver Box, the helpless little clerk broken in Justice, even the gesticulating emptiness of the post-war dare-devil who succumbs to the complex of Loyalties, are all, one feels, congenial to Mr. Galsworthy's rather nurse-like taste for weakness. He seems to prefer his little men and women to hang about his apron strings; and it is almost always the Red Cross, scarcely ever the fiery cross, that Mr. Galsworthy raises.

Yet, on the rare occasions when he has tried for larger game, his success has been proportionately large. The world, outside those humanitarian circles where conscientious objectors were more than casualties, is strangely unmoved by the tragedies of weaklings; but the clash and fall of stronger men is the true material of drama. Once at least, in Strife, Mr. Galsworthy has achieved the greater performance and set in motion two genuine, developed, adult persons down the long road which ended in "a woman dead, and the two best men both broken." That play is a singularly faultless piece of work.

(Continued on page 68)

(Continued from page 34)

One feels too often with Mr. Galsworthy that he is wasting his pity; and one hates to see the milk of human kindness being poured away, as he too often and too lavishly pours it, on the sands. Mr. Galsworthy so frequently weakens a sound play by arguing a weak case. But in Strife, one is never distracted from the march of the tragedy by a flaw in the argument. One was disinclined to be persuaded of the futility of a whole system of law because the Magistrate in The Silver Box omitted to sentence a rich young man for an offence with which he was not charged; or because the sentimental embezzlement of a solicitor's clerk, in Justice, was punished, rather than rewarded, by society. But Mr. Galsworthy's case in Strife is unanswerable, and his dramatic handling of it is quite impeccable. Any economic system which maintains, in a position of authority, employers of labour who resemble Mr. Norman McKinnel as closely as John Anthony, stands condemned. The author starts with our intellectual sympathies, and we are prepared to let him prove his point in three acts. Yet he does better. Any Fabian could demonstrate the farce of the existing order in British industry. But it takes a dramatist to make a tragedy of it.

THE rare grip of Mr. Galsworthy's plays is only half due to their subjects. They owe the other half to the fine concentration of his method. You will never find, in any one of his pieces, that there is a word in the mouth of any character which is not strictly relevant to the tussle round which the play is built. There are no stray snatches of conversation, none of those little irrelevances of which real life is so full; because, if you are to state a case in three hours, there is no time for them. His people are exhibited with the one or two salient points of character which are necessary for the play; and one can hardly imagine them in any other situation. One seems to see them always in relief; never in solid, three-dimensional sculpture. The method—one may call it economical or meagre, according to taste—suffices admirably for the drama. But for a novelist (and Mr. Galsworthy writes novels), it is a frail equipment.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now