Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Citizen King

Concerning—Not Louis Philippe of France, But Mr. Stanley Baldwin of England

PHILIP GUEDALLA

ONE of the most engaging of human fallacies is the undying belief that great events must, somehow or other, produce great men. Our own age, indeed, goes almost further and proclaims with every headline and every hoarding at its command, that great men grow bn every bush that flourishes along every single walk of life. For greatness, if press announcements and small handbills can be believed, is the badge of all our tribe. In a life of average length I cannot remember having listened to a pianist w-ho was not a Great Pianist. Nor is the keyboard the sole avenue to superhuman eminence. For the mere touch of a bow, the feel of a fiddle under the jawbone seems to confer Greatness in an instant; and the same gratifying effect appears to follow the briefest acquaintance with the harp, the 'cello, and even (in extreme instances) the wood-wind. Similarly, I have rarely turned a drowsy eye upon a morning paper without learning with pleased surprise that the speech, which ensured my perfect night, was a Great Speech.

And readers of fiction will, I think, bear me out in the cautious statement that we never read less than six (though rarely more than twenty) Great Novels in a year. Indeed, I understand that some publishing houses make it a rule never to issue more than four each season.

THE tide of greatness rises upon us with a terrifying rapidity and begins to fill us with some of the emotions which rose in Noah, as he heard the diluvial rain drumming against his windows, packed his bundles, and went out to look for two of everything. For the great, you may almost say, we have always with us. They arc everywhere, and growing greater every day. But I am struck suddenly by the reassuring thought that these alarms are possibly ill-founded. Perhaps 1 overrate (I hope I do) the humble superlatives of advertisement, the simple-minded enthusiasm of press-agents. Perhaps they are not really all so great. I am sure I hope not.

But there is still one sphere in which the process of factitious greatening is quite shamelessly carried on. The great event seems almost irresistibly to set us searching for great men; and then, if there arc none in sight, we select a man of ordinary dimensions and magnify him. What more vivid example than the Great War? Soldiers and statesmen of normal (and sometimes less than normal) calibre have been magnified out of all recognition, simply because the accident of birth, a coincidence of party politics, or just their wretched luck involved them in a first-rate historical incident. Fate has inflated their tiny reputations, like the banknote-issue of an insolvent Balkan state. Some still survive in this uncomfortable condition. But most of them have burst under the strain; and historians arc already busy piecing together the fragments to ascertain what size they really were.

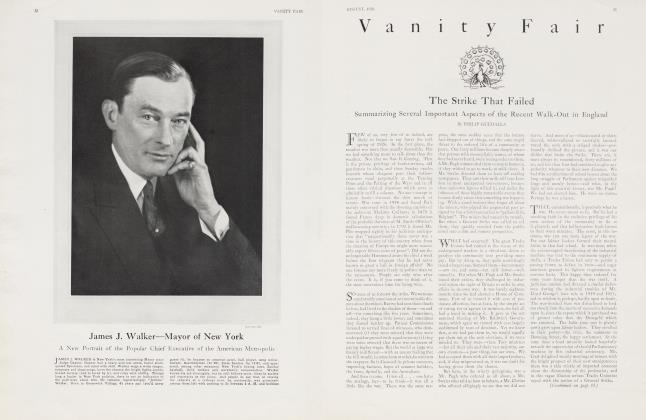

As the Great War, so the Great Strike. I have already done my best to state the issues and the outcome. But that singular event was' no less remarkable in its effect upon individual reputations. Since it was a great event, wc all began instinctively to look for a great man. For there had never been a great event without a great man. Did it not say so in the history books? The Labour side was not, it must be confessed, unduly rich in figures apt for greatening. We knew too little of Mr. Swales, too much of Mr. Thomas, to erect them into magnificently Satanic figures, Princes of Economic Darkness. Few capitalist infants were rocked to sleep with the menace that Mr. Citrine would catch them if they didn't. But scarce as such figures were on the other side, they were still scarcer on our own. One could not wield a fearless truncheon in a batoncharge with the heartening cry of "St. George and Lord Birkenhead". The official intimation that Sir William Joynson-IIicks expects that every man this day will do his duty struck feusparks from constabulary bosoms. So we made Mr. Baldwin do.

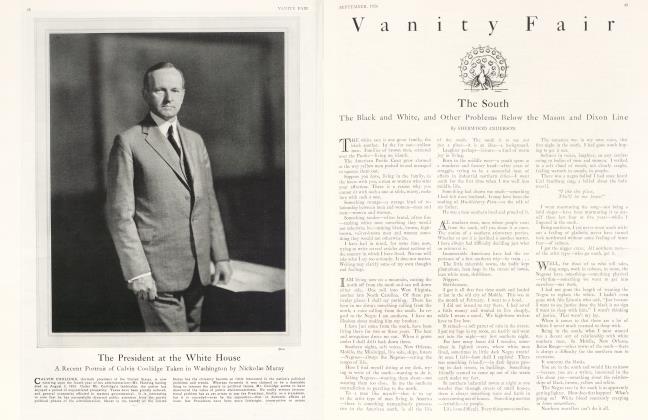

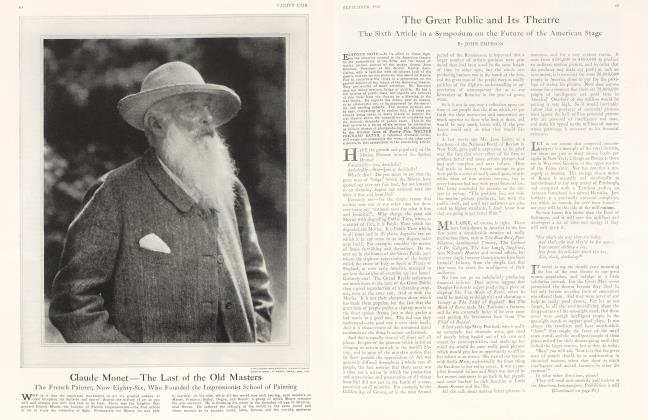

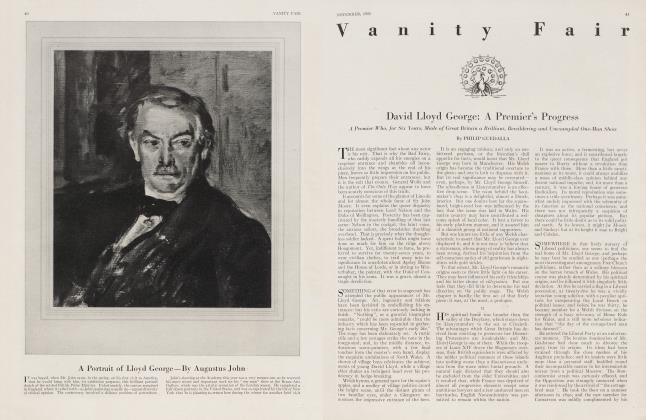

THE fame of Mr. Baldwin is, to the historical student, quite the most interesting product of the General Strike. His personal prestige became immense. Wholly apart from the respectable facts that he was Prime Minister and leader of the most numerous party in the country, he suddenly became a figure of enormous power. The raw material for greatness was not conspicuously promising. Known to grateful shareholders as an industrialist and to a more limited circle as a determined agriculturist, he had become Prime Minister for the simple reason (it seemed sufficient at the time) that he was not the late Lord Curzon. Three years ago, when that sudden rise left England a little breathless, I remember writing in a slightly fevered effort to appraise the new luminary that "Pigs and a brisk, determined geniality were the banners behind which Mr. Baldwin marched into office". And that was very nearly all that wc knew about him. Since that time he had, it must be confessed, been guiltless of any particular achievement. A few months after his promotion a sudden impulse made him fling his Party into a wholly unnecessary election on the one issue upon which they were quite certain to be beaten. They were; and for nine months of Opposition he bore their resentment, until the Socialists with almost equal imbccilitv flung themselves out of office. Then he returned; and his second reign began with a striking speech upon good-will in industry. He became almost at once the apostle of good intentions. His simple honesty had already been advertised almost to satiety and in a slightly invidious tone which seemed to imply that all other public men were pickpockets or incendiaries. This was the least attractive feature in the public building of Mr. Baldwin's reputation. Perhaps his own part in it was small, although his elaborate modesty (and frequent pipe) seemed to lend countenance to a slightly distasteful propaganda.

But his tone on industrial questions found a wide welcome. The younger Liberals had faced for years the problem of industry; and even the common citizen was beginning to realise that all, between master and man, was far from well. So it was pleasant to discover a Prime Minister whose intentions, at least, were good. But long before he could find means to carry them out, his life—and every life in England—was interrupted by the General Strike. Then, quite unexpectedly, his good intentions became a public asset. For it was vital, if we were all to be united in defence of the state, that it should be clear beyond all doubt that wc were not asked to unite in defence of Big Business. Wc knew, indeed, that Mr. Baldwin was a large employer. We knew also that his Party included all that was Biggest in the nation's Business. But, fortunately, wc knew a little more than that. Had he not told us of his good intentions? Wc had believed him—and, still more significant, Big Business had believed him, too. Those shrewder judges, who see life from board-room windows and sit high in Tory counsels, had listened with obvious concern to their leader's views upon industry and regarded him in consequence with faint suspicion. That was his own passport to public esteem. We had heard the stiffer kind of reactionary call him "a sort of Socialist"; wc saw the hands of Interests raised when his name was mentioned; wc knew that the great employers felt a little unsafe beneath the vague menace of his good intentions. That was the best sign of all. He was not a "hard-faced" man; no Geddes he; we learned with audible relief that there are certain industrial purposes for which gentlemen prefer Monds.

THAT realisation in the public mind gave him his strength during the crisis. The common man, who was invited to drive a lorry or carry a truncheon, felt that he was not being made the tool of Big Business in an aggressive war against the worker. And the worker, who would have preferred to gesticulate at some monstrous emblem of Big Business, saw in Mr. Baldwin the embodiment of the common man. That fact lent half its strength to the civic effort against the Strike and removed the sting from half the speeches of excited agitators.

I think we all believed in his good intentions. We certainly believed his word—and that was something, when it came to negotiations. How far he can impose those intentions on a rebellious and triumphant following is another and a more arduous question. But all of us believe that he will try. In the struggle itself he emerged a little as King Louis Philippe emerged upon the French imagination, sickened with the long parade of kingship, as a Citizen King.

We are a little weary of heaven-sent ministers, with their pretence of inspiration and their arrogant parade of "first-class brains". We think, to tell the truth, that we could all do nearly as well ourselves; and wc arc a little cheered by the sight of one of ourselves trying his hand. For wc have been deafened bv the claims of greatness. Now, Mr. Baldwin is not Great: perhaps they never are.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now