Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

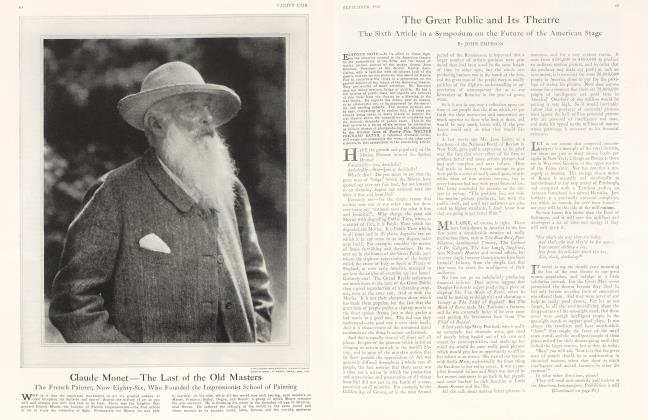

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowFour-Card Suit Bids

Their Advantage as Alternatives to No-Trumpers on Bad Suit Distributions

R. F. FOSTER

GOOD bridge players have always been willing to bid four-card minor suits, clubs or diamonds, if they measure up to the modern rule of four tricks in the suit, or in the whole hand, counted on the double-valuation system. This bid has always been limited to the dealer, or to the second hand if the dealer passes. Minor suits arc not bid with any idea of insisting on them for the trump, unless the player is willing to bid four or five, but rather to show the partner that there is more than average strength in the hand so far as trick-taking is concerned, and the old rule still holds: Minor suits offer assistance; major suits ask for it.

Here are two interesting examples of fourcard minor-suit bids, both played in important duplicate games:

On A, the only player who started with a club bid was E. V. Shepard, the author of several books on auction bridge. His adversaries went to five spades over his partner's five hearts and the club lead set the contract two tricks. Every other pair in the room lost a grand slam in spades, as the opening lead was a heart.

On B, the only player that bid a diamond as dealer got a diamond lead against a contract to make three spades, doubled and redoubled, and set the contract one trick. Every other table made four spades.

Some of our advanced players have long been in the habit of bidding four-card major suits, but it is only lately that the bid has become generally known to the great mass of bridge players. This is undoubtedly due to the example set by original players like Mr. Eli Culbertson, who was the first to insist on the importance of considering the general suit distribution of the hand as a whole, rather than the high cards in any particular suit. His theory was fully explained in the January, 1923, number of this magazine.

SUIT OR NO-TRUMPS?

ONE of the first results of the introduction of bidding on suit distribution was that it called attention to the weakness of such notrump bids as those in which there was more than one suit of only two cards; or singletons, or a wholly missing suit. This restricted the average no-trump bid to one of three suit distributions:

4 3 3 3 4 4 3 2 5 3 3 2

The distribution 5 4 2 2 is classed as a border-line no-trumper, and at least one of the short suits should be headed by a sure trick, ace, or both king and queen, the five-card minor suit not promising as good a chance for game as no-trumps. T he same is true, in loss degree, of the 6 3 2 2 distribution, in case the minor suit of six cards does not promise game. If both the short suits arc stopped, notrumps is the better bid. Here are examples:

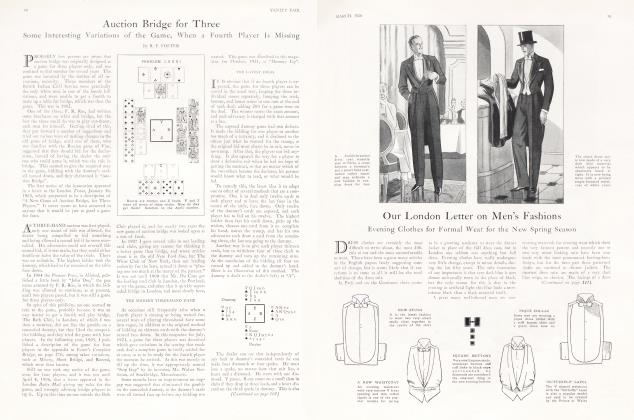

Hearts are trumps and Z leads. Y and Z want all seven of these tricks. How do they get them? Solution in the October number

It would be unwise to waste either of these on a club bid, which would almost certainly be left in, as the average of two tricks in the dummy will not reach game in clubs, while it would at no-trumps.

As the five distributions given above are more common than any others, and comprise nearly two-thirds of all the hands held by a dealer, or by second hand il the dealer passes, (637 out of every 1,000 by calculation) we get down to a choice between bidding a suit or notrumps, provided the hand as a whole is strong enough for a no-trumper, with three suits stopped.

The rule now generally followed seems to be that if there is no five-card major suit and only one short suit (two cards) there is no necessity to prefer a four-card major suit to a no-trumper, unless the major suit contains at least three high honours. If there are two short suits of two cards only, both safely stopped, the same rule applies. It they are not both stopped, bid the suit.

Here are two hands in which there might be some doubt in the bidder's mind:

In E no one can find fault with either bid, hearts or no-trump; but in F, with only one stopper for the two short suits, the heart is the better bid. If partner denies the hearts with spade, then this is a no-trumper. If the adversaries bid spades, the best defence has been indicated.

If the suit distribution is unfavourable for no-trumps, the choice between a four-card major suit and a live-card minor should be in favour of the major suit if it is headed by what would be rated as three tricks on the doublevaluation system; that is, not weaker than A J 10, as A Q is more of a border-line bid.

G is too good for a club and bad suit distribution for no-trumps, but is a sound spade bid. H is too weak in hearts for a four-card bid, and too good to waste on diamonds. With one short suit safely stopped, bid no-trump.

As an example of the change that the transposition of one or two small cards may make in the selection of a bid, take these examples:

IN J, the distribution is excellent for a notrumper, and there is no objection to the heart bid. No one can dogmatize that either bid is better than the other. In K, on the other hand, the singleton is a danger signal, although it would not have been so regarded a few years ago, and the heart is better than clubs.

FOUR-CARD SUIT OR PASS?

The modern system of bidding four-card suits in preference to no-trumps on certain types of hands has led to bidding fourcard major suits on many hands which have no pretensions to being no-trumpers, and which would have been passed up without a bid by the majority of bridge players before suit distribution was studied.

These modern bids are still governed by the qualification that was published in connection with all four-card suit bids fifteen years ago: "Any deficiency in high cards or length must be made up for by winning cards in other suits." These are still called "compensating tricks", as they were then.

It is now generally conceded that if one has any five-card suit headed by two sure tricks, such as ace-king; ace-queen-jack; or kingqueen-jack, that is a good bid in itself, regardless of the rest of the hand. Counted on the double-valuation system these two sure tricks will average four in the play of the hand.

(Continued on page 124)

(Continued from page 85)

It is a simple matter to count the bidding value of any hand on this system, but we have to make a double adjustment for suits of only four cards. First, to be sure that the entire hand would be worth four tricks if there were five cards in the suit, and then to compensate for the missing cards in the trump suit.

W. H. Whitfeld, for many years card editor of the London Field and noted for his many contributions to the mathematical probabilities in auction bridge, found by experiment and calculation that any extra trump should be regarded as replacing what would otherwise have been a losing card in the hand. Conversely a winning card should be regarded as replacing a missing trump.

Suppose one holds five hearts to the ace-king and two losing clubs. If we take away one of those clubs and replace it with a trump it is obvious that we have only one losing club, and if there are still trumps enough to justify the bid after calling one of them a club, that extra trump is worth a clear trick. Count these hands:

In L, the ace-jack-ten is worth 3, the club king 1, total 4, and therefore a sound heart bid. In M, the hearts are still worth 3, and the king-queen of clubs 2, total 5. The extra trick in clubs makes up for the shortness in the trump suit. One must either bid the suit or pass. A timid player might bid a club on M, in order to hear from other bids. They call this "an approaching bid".

If Whitfeld's analysis is correct and the double-valuation system is dependable, we get the following simple rule for the difference between bidding on four-card major suits and waiting for five:

For a bid on five trumps we require a minimum of four tricks in the hand, at least two of which should be in the suit named.

For a bid on four trumps, we require a minimum of five tricks in the hand, at least three of which should be in the suit named.

In the examples repeatedly given by some writers on the game we find that only half of them comply with this simple rule, the others being all above or below the standard. Here are two examples:

In N, if we take away the ace or clubs and put a small heart in its place, there is no sound heart bid on the five cards, as the hand is worth only two tricks. The same is true of O, because if we replace the ace of clubs with another heart the whole hand is worth two tricks only, instead of four.

SOME CLOSE DECISIONS

There are undoubtedly many hands in which the player's judgment is as good as any rule when it comes to deciding whether to bid a four-card major suit, or a minor suit, or to pass, but a few examples may help the reader to sec the general principles underlying all these bids.

In P, the added queen of trumps is about as good as two small ones, with the added possibility of partner's having a fourth honour to score. In Q, the spades are too weak. Bid the club.

In R, the usual rule about bidding the higher ranking of two equally good bids holds. Start with the spade. But in S, the hearts must be named, as the spades have not the requisite intrinsic strength for a free bid.

In T, we have not the full strength for an original heart bid, but as it is the dealer's intention to bid the spades if he has an opportunity, he must show the suit in which he has the sure tricks while he has the chance to do so cheaply. In U, we have three possible bids, all of which were made at various tables in a duplicate game. Those who started with a spade got the best results, going game, as the partner supported it over clubs as an original bid, but did not support it as a secondary bid.

The following are not sound fourcard major suit bids, although that bid was made upon them at several tables in the same duplicate game:

In V, the hand is worth four tricks only, and if we replace the spade ace with a trump, the hearts are worth only two. In W, if we call the club king equal to a trump, the spades are worth three only.

THE PARTNER

The partner cannot tell when a bid is on four cards only, and must assist and deny as if it were the usual five. It is the dealer who will not know what to do when it comes to going on, the danger being that his partner has two only. Seven times out of ten he will have three, or more, and one-third of the time he will have four, or more.

(Continued on page 126)

(Continued from page 124)

When dummy has four, it is a stronger hand than if the trumps were divided five and three, as either hand can ruff without weakening the other. But when dummy has two only, the dealer four, care must be taken to get the first force on the adverse fourtrump hand. The hand shown in example J was played in a duplicate game, and one dealer, who was an expert player, bid a heart. At other tables, bidding no-trumps, the dealer was taken out with two spades and on the play made five, but the honour score left the result in favour of the heart bid, as both went game. Here is the play:

The club seven was led, and Mr. Finessky made an entirely unnecessary finesse (by the eleven rule) winning with the ten and returning the ace, which dummy trumped, marking Mrs. Fourbest with three clubs left.

The obvious play is to lead the king of trumps, get in with a diamond, draw the trumps, and trust to the diamonds being split. The expert did not play the hand that way. He kept dummy's trump to stop the clubs while lie tried out the diamonds. When the ten fell, it could hardly be a false card, so he credited Mr. Finessky with four diamonds to the eight, if not five to the jack, and switched to the ace and another spade. The second spade was won by the king.

This marks Mrs. Fourbest with the four-trump hand, three clubs and one diamond, the jack. The end-game, therefore, resolves itself into a neat little eight-card problem, the declarer and dummy to win seven of the remaining tricks against any defence.

ANSWER TO THE AUGUST PROBLEM

This was the distribution in Problem LXXXVI:

Hearts are trumps and Z leads. Y and Z want six tricks. This is how they get them:

Z leads a diamond, which Y trumps. Y then leads the spade queen, and B ducks it. Z overtakes the queen with the king and leads another diamond and again Y trumps. Y now leads the spade nine, and again B ducks, allowing Z to overtake the nine with the ten, leading the third diamond, which

Y trumps. This allows Y to lead the eight of spades, and it is impossible for B to make anything but the ace.

The idea of this problem is to exhaust B's diamonds, so as to compel a spade lead eventually, in case B holds off the spades until the third round. As will readily be seen, if B wins the first or the second spade lead, he immediately establishes the rest of the suit for Z, so that the spade ace (or the club jack) is the only possible trick for A and B.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now