Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowRetired Statesmen

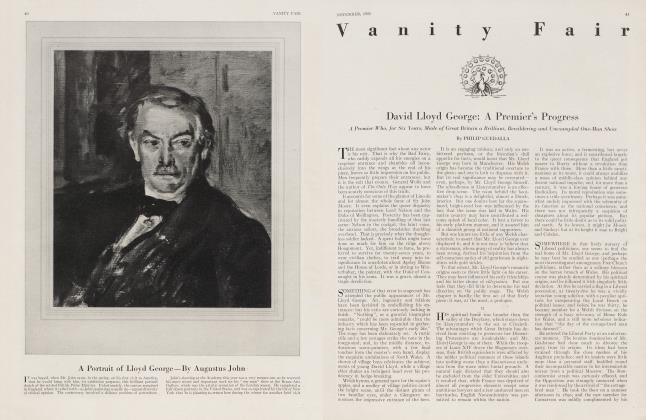

And the Survival of Mr. Lloyd George as a Rococo Ornament of His Period

PHILIP GUEDALLA

IN the West End of London, an astute and enterprising theatrical manager has been regaling his patrons with a galaxy of fallen stars—the favorites of an earlier and happier day.

Old heads in the audience are set nodding to the beat of tunes that have long since faded from provincial barrel-organs, and feet, which are no longer so young as they used to be, keep time to airs so old that even the youngest errand-boy no longer whistles them. There is a quick rattle of forgotten repartee, and the old faces brighten as the fun of cross-talk grows fast and furious, as it used to grow when Queen Victoria was Defender of the Faith and gay young gentlemen in evening dress paid hansom cabs with half-sovereigns outside the Tivoli.

It is a very pleasant experience, even for the hard-eyed generation which believes that light music was always syncopated and that the most entertaining performers came over with the Gulf Stream. The study of origins is always stimulating, and one can enjoy it better still when it becomes the excuse for an act of slight kindness to the origins themselves.

The march of Progress (it is noticeably more rapid in the theater than in foreign affairs) is sometimes a little ruthless. Popular numbers, if one may adopt the dialect of the program, soon become back numbers, and figures that once topped the bill are quickly elbowed into the wings and down the draughty corridor that leads out into the daylight. For that reason, among others, one is glad that a little room has been found for old favorites.

Something of the same kind might perhaps be done in politics.

The Uncertain Glory

THE politician serves a queer public. So long as he satisfies the taste of the moment, his position is assured. The fierce light that beats on thrones and prize-fighters is dim compared with the glories of his publicity. His dogs, his country seat, his favorite flower, are presented daily to an eager community. Hungry supporters struggle for his old golf balls, and the public mind treasures his lightest sayings even on subjects with which he is imperfectly acquainted.

But when the change comes, when the bottom drops out of his market and Ihe world goes past him, the voice that was once so sonorous is left twittering in solitude, and its master is marooned in obscurity like poor old Ben Gunn in the lonely sunshine on Treasure Island.

It is a spectacle which one can hardly observe without sympathy. There is something infinitely pathetic about the long career of Lord John Russell for twenty years after he had ceased to matter. If only, one feels—if only they had let him introduce a Reform Bill or so just for old times' sake, how the old eyes would have sparkled and the old voice forgotten to shake! How much more fortunate was Pitt, who died in harness, or Chatham, who died almost in debate! There is the same futile, half pitiable flavor about the figure of Wellington plodding on quite alone, until most of his younger contemporaries had almost ceased to care whether he had won the war or not.

And one can think of more recent examples.

Sic Transit Lloyd George

THEY make a strange study. Present fashions change more quickly; and within a year one has seen a Prime Minister fade out of power into a repose which is not even interrupted by the leisured dignity of leading the Opposition.

The old activities of Downing Street seem half a century away from Mr. Lloyd George. The crowding deputations, the smiling Conferences that used to face the camera (on garden seats) and astonish the world with reiterations of that perfect, too perfect, Allied unanimity, belong to the history books. The central figure, which was once so near and which cast so very broad a shadow, seems slowly to have receded into the long perspective of history.

Yet it is all only a few months away. Last autumn he was in office; and a year before that he was enthroned at Gairloch, a Dictator who (unlike Cincinnatus) obstinately declined to leave the plough and insisted that the business of the State should be transacted at his plough-tail in the distant field. It is a singular transformation. But one can hardly fail to realize it.

It almost seems as though there had been a sudden change in the public taste, one of those abrupt twists of fashion which leave modistes bankrupt or turn stage favorites into curiosities. The public, if one may attempt to read its mind, had stared for quite long enough at its masters in the limelight. Its eyes were growing a little tired and there was a sudden craving for something in a quieter style. They had been bewildered by a peripatetic succession of Peace Conferences whose itinerary made the map of Europe look like an illustration to the Acts of the Apostles; and they longed for nothing so much as a seat of Government which would stay in the same place for a few months at a time. They had been dazzled by the intimate touch and deafened by the personal note; and they were searching desperately for a few public men who would confine themselves to their public life.

That is how British politics came to enter the drab phase of 1923. British politicians have become almost impersonal. No one could tell you the name of Mr. Bonar Law's favorite tune or Mr. Asquith's pet seaside resort; Mr. Ramsay Macdonald is but rarely photographed on a pit pony, and Mr. Baldwin's cherry-wood pipe alone survives from the rich repertory of personalia with which our public men were once decorated.

Elba or St. Helena?

PERHAPS a little damped, perhaps (who knows?) slightly relieved, Mr. Lloyd George survives into the new era. Once the richest, the most rococo ornament of his period, he seems now an odd survival of an old style. He has. still his peregrinations about Europe, "in the fearless old fashion". But he is writing his memoirs. He is even (proh pudor!) writing for the newspapers— and that, for a politician, is the equivalent of acting on the films for a lady of fashion.

Yet the little figure is not quite still. Perhaps his retirement of 1923 is no more final than Mr. Gladstone's of 1876. Nobody—least of all himself—can tell. But if he returns, it will be with the same faint flavor of old melodies and old back-chat that a clever manager has brought back to the London stage.

This is the third of a series of sketches of contemporary celebrities—literary and political —which Mr. Guedalla is contributing to VanityFair. Within their smaller scope they exhibit the same literary dexterity and picturesque historic sense which have been seen to such ample advantage in his history of the Second Empire..

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now