Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowAmerica's Classic Murder

Professor Webster, of Harvard, Makes a Final Settlement with Dr. Parkman

EDMUND PEARSON

(The First of a Scries of Murder Stories by Mr. Pearson)

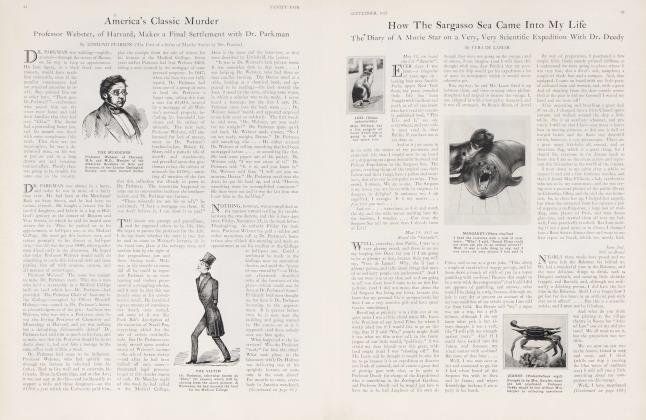

DR. PARKMAN was walking—rapidly, as usual—through the streets of Boston, on his way to keep an appointment. His lean figure, in a black frock coat and trousers, would have made him noticeable, even if his peculiar countenance had not attracted attention by itself. Boys pointed him out to other boys. "There goes Dr. Parkman!" —and women who passed him on the street went home and told their families that they had seen "Chin." The doctor had a protruding lower jaw, and his mouth was fitted with some conspicuous false teeth. That chin was not meaningless; lie was a determined man, on his wav to put an end to a long drawn out and vexatious business affair. Plainly there was going to be trouble for some one in the vicinity.

DR. PARKMAN was always in a hurry, and today he was in more of a hurry than ever. He had been at the Merchants' Bank on State Street, and he had been on various errands, lie bought a lettuce for his invalid daughter, and left it in a bag at Holland's grocery at the corner of Blossom and Vine Streets, to which he said he would soon return for it. Then he pushed on to his appointment, at half-past one, at the Medical College, lie must get this business over, and return promptly to his dinner at half-past two,— for this was the year 1 849, when gentlemen dined early in the afternoon. He hoped that today Professor Webster would really do something to settle this infernal debt and cease putting him off with evasions, excuses, and all manner of subterfuges.

Professor Webster! The name was enough to make Dr. Parkman snarl. This was a man who held a lectureship in a Medical College built on land which he—Dr. Parkman—had provided. The Parkman Chair of Anatomy in the College—occupied by Oliver Wendell Holmes-—was named in Dr. Parkman's honor, as acknowledgement of the gift. And here was Webster, who was twice a Professor, since he was also Fixing Professor of Chemistry and Mineralogy at Harvard, and yet was nothing but a defaulting, dishonorable debtor! Dr. Parkman had told him as much to his face, and to make sure that the Professor should be in no doubt about it, had sent him a message to the same effect both within a week.

Dr. Parkman had cause to be indignant. Professor Webster, who had quickly run through the fortune he inherited from his father, liked to live well and to entertain his friends. Even in Cambridge, and at that date, it was not easy to do this—and incidentally to support a wife and three daughters—on the $1200 a year which the University paid him, plus the receipts from the sale of tickets for his lectures at the Medical College. Seven years earlier Parkman had lent Webster ;400, taking a note secured by the mortgage of some personal property. In 1847, when the loan was not fully repaid, Dr. Parkman had been one of a group of men to lend the Professor a larger sum, taking this time a note for ;2,432, secured by a mortgage of all Webster's personal property, including his household furniture and his cabinet of minerals. The next year, Professor Webster, still embarassed for lack of money, went to Dr. Parkman's brother-in-law, Robert G. Shaw, told a pathetic tale of sheriffs and attachments, and prevailed upon that gentleman to buy the cabinet of minerals for ;1200,—omitting all mention of the fact that this collection was already in pawn to Dr. Parkman. The transaction happened to come out in conversation between the brothersin-law, and Dr. Parkman was furious.

"Those minerals arc not his to sell," he exclaimed; "I have a mortgage on them. If you don't believe it, I can show it to you!"

THE doctor was prompt and punctilious, and he expected others to be like him. He began to pursue the professor for the debt. I do not know whether the storv is true that he used to come to Webster's lectures, sit in the front row, glare at the unhappy man, and confuse him by the sight of that prognathous jaw and those shining teeth. Webster, in the months to come, did all he could to represent Parkman as an overbearing and violent persecutor of a struggling scholar, and it may be that this was merely some of his corroborative detail. He furnished a great amount of corroborative detail, once started, and some of it was like Pooh Ball's description of the execution of Nanki Poo, everything added for the sake of artistic verisimilitude. But Dr. Parkman certainly moved upon another source of Webster's income —the sale of lecture tickets —and after he had been fobbed off once more— threatened legal processes to get at this slender source of cash. On Monday night of this week he had called at the Medical College.

Here is the scene and the interview, as they were described by Littlefield, the janitor.

"It was in Dr. Webster's back private room. It was somewhat dark in that room ... I was helping Dr. Webster, who had three or four candles burning. The Doctor stood at a table, looking at a chemical book, and appeared to be reading;—his back toward the door. I stood by the stove, stirring some water, in which a solution was to be made. I never heard a footstep; but the first I saw, Dr. Parkman came into the back room . . . Dr. Webster looked 'round, and appeared surprised to sec him enter so suddenly. The first words he said were, "Dr. Webster, arc you ready tor me tonightr" Dr. Parkman spoke quick and loud. Dr. Webster made answer, "No I am not ready, tonight, Doctor." Dr. Parkman said something else . . . He either accused Dr. Webster of selling something that had been mortgaged before . . . or something like that. He took some papers out of his pocket. Dr. Webster said, "I was not aware of it." Dr. Parkman said, "It is so, and you know it." Dr. Webster told him, "I will see you tomorrow, Doctor." Dr. Parkman stood near the door; he put his hand up, and said, "Doctor, something must be accomplished tomorrow." He then went out and it was the last time that I saw him in the building."

NOTHING, however, was accomplished on the morrow toward settling the trouble between the two doctors, and this is four days later, Friday, November 23, in the week before Thanksgiving. An unlucky Friday for both men. Professor Webster has paid a sudden and rather mysterious call at Dr. Parkman's house before nine o'clock this morning and made an appointment to see his creditor at the College at half-past one. Could a settlement be made at the College, near an anatomical theatre, and amid the "pieces of sour mortality"—as Dickens afterwards described some of the furniture of the place—which could not be done at Dr. Parkman's home? Evidently both men thought so, tor here is Dr. Parkman hastening to the appointment. It is quarter before two; he is seen near the building and going toward it. He enters—or so it is supposed—and then, nobody ever secs him again.

What happened at the interview? Was the Professor "ready" for him this time? What took place in the laboratory while Dr. Holmes was delivering one of his sprightly lectures on anatomy in the room above? For months to come, cvervbodv in America wondered, and numerous dignified citizens, university officials, and officers of the government worried about it until literally they became grey-haired over the problem. And after nearly eighty years it is still something of a mystery 5 vve do not know exactly how or why the thing happened. After shiftings anil evasions, after solemn denials and terrific perjuries, and when he was very near the gallows, Professor Webster gave an account of the meeting, which may approximate the truth.

(Continued on page 88)

(Continued from page 44)

According to this story, Dr. Parkman, on entering the laboratory, instantly began to demand payment, to call the Professor a "scoundrel" and a "liar," and to go on with "bitter taunts" and "opprobrious epithets." He refused to listen to Webster's pleas for time, hut shook his fist in his debtor's face.

"I got you into your professorship," he shouted, "and now I'll get you out of it!"

Webster's temper was soon aroused, as it may very well have been. In a sudden rage, he picked up a stick of wood—the stump of a grape-vine, about two feet long, and killed Dr. Parkman with a single blow on the head. As soon as he found that his persecutor was indeed dead, the Professor instantly lost his own wits. Instead of declaring his crime, and pleading the provocation, which coupled with his own good reputation, might have caused the offence to he regarded as manslaughter, he was seized with abject terror and the idea of concealment. He started upon the complicated and ghastly business of disposal of the body.

Such a man as Dr. Parkman could not casually disappear from the streets of Boston in broad daylight without causing excitement. He was too prominent and too highly connected. Although he was a Doctor of Medicine of the University of Aberdeen, he did not seem to have practised as a physician, but to have devoted himself, too energetically, to business and finance. His brother was the Rev. Dr. Parkman, hut his nephew, then a young man recently from college, was to become more distinguished than any of them, as Francis Parkman, the historian. When Dr. Parkman did not come home to dinner that Friday afternoon his family were alarmed, and by the next day were in great agitation and distress. Advertisements offering rewards were put in the newspapers, the river was dredged, empty buildings and cellars were searched. On Sunday afternoon Professor Webster paid a sudden and surprising visit at the Rev. Dr. Parkman's house and aroused astonishment by his abrupt manner. The Professor made one of his numerous mistakes, and acknowledged having had an interview with the missing man on Friday afternoon. According to this account, however, they had parted at the end of the interview. To other persons about the College the Professor said that he had met the doctor on Friday by appointment, had paid him $483 and that the doctor had rushed out with this money in his hand. The inference served to bolster up the popular theory that Dr. Parkman had been waylaid somewhere, robbed and murdered.

(Continued on page 96)

(Continued from page 88)

The suspicions of Littlefield, the janitor, were aroused early. On Monday, the day of the interview between the two men in the laboratory, which he had witnessed, Professor Webster had asked him about the condition of the vault, where remains from the dissecting room were placed. On Thursday, the day before the disappearance, Webster had sent Littlefield on an unsuccessful errand to the Massachusetts General Hospital to get a pint of blood, which the Professor said he needed to use at his lecture. On the days following Friday, and for nearly a week, Professor Webster was often locked in his laboratory at unexpected times. The janitor could hear him walking about, could hear water running in the sink, and he discovered that unusual fires were burning in the assay-furnace. Webster's actions and manner were strange during all this time, and at last he completely astounded the janitor, on Tuesday, by giving him an order for a T hanksgiving turkey. It was the first gift he had ever made to Littlefield in an acquaintance of seven years.

Finally, Littlefield became tired of hearing on the street that Dr. Parkman's body would probably be found in the College, and he resolved to investigate a vault below Professor Webster's own apartments. Only superficial examinations of the College had been made so far, in the searches which were going on all over Boston and Cambridge. But the janitor, with crowbars and chisels, and with his wife on guard to warn him of the approach of Webster, put in parts of two or three days trying to break through a brick wall, and inspect the contents of the vault. Thanksgiving was a gloomy day with him, in spite of Professor Webster's turkey, for he spent the morning cleaning up his own cellar, and the afternoon pounding and prying at the tough courses of brick in the vault. He got some relief at night, however, when he went to a ball given by the Sons of Temperance, where he stayed until four o'clock in the morning, an.d danced eighteen out of the twenty dances. Ah, there were janitors in those days!

On Friday, one week after Dr. Parkman's disappearance, Littlefield broke through the wall, and looked into the vault. "I held my light forward," he said, "and the first thing which I saw was the pelvis of a man, and two parts of a leg. The water was running down on these remains from the sink. I knew it was no place for these things." College professors and the City Marshal were notified; three police officers were sent to Cambridge to bring Professor Webster to Boston, and put him under arrest. He was dreadfully agitated; he made remarks which amounted to expressions of his having suspicions against Littlefield; he attempted to commit suicide by taking poison, which did not kill him, although it. left him almost paralyzed for many hours.

John White Webster was by way of being a scholarly man. He was M.A. and M.D. of Harvard; a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, of the London Geological Society, and of other learned bodies. He had written and edited books on chemistry and another describing one of the Azores, where his married daughter dwelt. Senator Hoar, who attended his lectures, said that he seemed "a kind-hearted, fussy person", whose lectures were intolerably tedious. Owing to the fact that he had insisted on having fireworks at the inauguration of President Everett, the students called him "Sky-rocket Jack".

When he was brought to trial in March, many persons still believed him innocent. Others thought that the charges against him would fail, for lack of proof that the remains were really those of Dr. Parkman. Some of his friends tried to induce Rufus Choate to undertake the defence, but that great attorney, after hearing the evidence, refused to enter the case unless the Professor would admit the killing, and try to convince the jury that it was manslaughter, not murder. This, the Websters refused to consider. Those who, like Charles Sumner, still believed in the Professor's innocence, probably did not understand the strength of the evidence which was to be brought forward. In addition to a number of feats of juggling with checks and notes, which the defence could not explain, there were fragments of mineral teeth found in the furnace, and of other larger parts of a human body in a tea-chest filled with tanbark. And the Professor had had a quantity of tan-bark brought in from Cambridge during that week by Sawin the expressman.

The trial, before Chief Justice Shaw, is one of the land-marks in the history of criminal law in Massachusetts. Every one was impressed by the gravity of the occasion, and the proceedings were extremely dignified. The jury could not have been excelled for seriousness of purpose, and religious demeanour, if they had been chosen from the House of Bishops. To accommodate the great numbers of folk who wished to see something of the trial, the floor of the Court was closed to all but privileged spectators, while the general public were admitted to the gallery, where a change of audience was effected by the police every ten minutes! "Except for two tumultuous movements," order and quiet were preserved, and from 55,000 to 60,000 persons liad a glimpse of the proceedings. The trial lasted for eleven days, and the New York Herald, a paper of four pages, was one of many which adopted the extraordinary policy of reporting the events daily, in three or four closely printed columns, and on the front page!

(Continued on page 10-104)

(Continued from page 96)

The prisoner was not allowed to testify, at that period, but his counsel entered for him a complete denial. They raised doubts as to whether the pieces of a human frame were those of Dr. Parkman, and suggested that even if this were true, the fragments had been placed there by some person, unknown to Professor Webster, and, perhaps, in order to incriminate him. The tendency of the defence was to suggest the possible guilt of Littlefield. They tried to show, by witnesses, that Dr. Parkman had been seen later on Friday afternoon in other parts of the city.

Despite the strong net of circumstantial evidence closing around Professor Webster, the whole case for the State hinged on the proof of the identity of the remains, and in the final analysis, this rested upon the evidence about the false teeth. When Dr. Nathan Keep, a friend of both men, who had made some false teeth for Dr. Parkman, gave his positive evidence that these were the teeth and proved it by fitting the mould, still in his possession, to the fragments found in the furnace, he burst into tears, realizing that his testimony would hang the prisoner.

On the evening of the eleventh day of the trial the jury went out for three hours, and came in about midnight, with a verdict of guilty. Professor Webster was sentenced to death, but the usual appeals were made in his behalf. When the application for a writ of error was dismissed, the Professor addressed the Governor and Council, and in the most solemn language protested his innocence. Me used such remarkable phrases as these: "To Him who seeth in secret, and before Whom I may ere long be called to appear, would I appeal for the truth of what 1 now declare . . ." and "Repeating in the most solemn and positive manner, and under the fullest sense of my responsibility as a man and as a Christian, that I am wholly innocent of this charge, to the truth of which the Searcher of all hearts is a witness . . ." Some weeks later this address was withdrawn, and the wretched man made a long confession, maintaining that the murder was not premeditated. The account nf the death of Parkman, in this confession, has already been given. Upon these new assertions he based his petition for a commutation of the sentence. The Governor, however, could not admit that the prisoner's word was entitled to credit, nor did his pastor, nor some of his friends venture to suggest that he could be believed. Professor Webster was hanged on the last Friday in August, 1X50. He was calm, and apparently resigned.

Was it a coldly premeditated murder, or can it be considered manslaughter, done in sudden passion and under provocation: The question about the vault, the attempt to get the blood, and, perhaps, the appointment with Parkman at the College, point to a plan. On the other hand, he gave more or less plausible explanations of all these things, and the absurdity of any hope to make away with such a man as Dr. Parkman, and conceal the crime, is so great as to cast doubts upon the theory of premeditation.

The murder shows three things clearly: that a peaceable man may commit a crime of this nature ; that he will solemnly lie, calling upon the name of God, jeopardizing his hope of a future life to escape punishment here and now; and that a just conviction may be had upon circumstantial evidence. Even after the trial, there were folk who were unconvinced of the Professor's guilt, and A. Oakey Hall, afterwards Mayor of New York, was. one of those who "rote pamphlets to protest against the conviction.

The Webster-Parkman case has hardly been displaced as America's most celebrated murder, and the one which lives longest in books of reminiscences. Artemus Ward's show had "wax figgers" of both the principals, and few writers of the time failed to mention the crime. Of the anecdotes which are told about it, the story related by Longfellow, at the dinner to Charles Dickens, is perhaps the most remarkable. A year or two before the murder, Longfellow had been a guest at a men's dinner at Professor Webster's, to meet a foreign visitor, interested in science. Toward the end of the evening, the Professor had the lights in the room lowered, and a servant bring in a bowl of burning chemicals, which shed a ghastly glow upon the faces of the men about the table. Professor Webster rose, and producing a rope, cast it around his own neck like a noose. He then leaned over the hell-fires which, came from the bowl, lolled his head upon one side, and protruded his tongue in the manner of a man who had been hanged!

After the execution, it is said tint the Webster family removed to Fayal, where the married daughter lived. Some years later, there was a glib guest at a dinner party who had not caught the names of some of the Websters who were present, but merely knew that they had come from Boston. In order to make himself agreeable, he suddenly remarked: "Oh, by the by, what ever became of that Professor Webster who killed Dr. Parkman? Did they hang him?"

Another similarly gentle yarn is of a later date. Benjamin Butler was cross-examining a witness in Court, and treating him, so the Judge thought, with unnecessary brusqueness. He reminded the lawyer that the witness was a Harvard professor.

"Yes, I know, your Honor. We hanged one of them the other day!"

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now