Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowAuction Bridge Bids and Take-Outs

The Theory and Practice of Denying Normal Assistance for Partner's Bids

R. F. FOSTER

THE principle subject of discussion among bridge players since the last congress of the American Whist League, at which auction bridge was officially recognized for the first time, seems to have been the take-out of the partner's no-trumpers, when the second hand passes. This is now about the only part of the tactics of the bidding element of the game upon which the writers cannot agree; each having his own theory, unsupported by any facts.

The English players call the take-out, whether in a suit or no-trumps, "bidding against the partner." The American players call it, "arriving at the best bid for the combined hands." The theory of the take-out, among American players, is to inform the player making an unopposed declaration that he will not find normal support for his proposal in his prospective dummy.

For the sake of clearness in what follows it will be assumed that the first bid is for one trick only, and is made by the dealer; that second hand passes, and that third hand shall be known as the partner.

THE SUIT TAKE-OUT

WHEN the dealer starts with a bid of one in a suit he is supposed to have just an average holding in that suit and to be depending on his partner for normal assistance. This has been established by both theory and practice, backed up by analysis of hundreds of deals, as a minimum of three small cards, or two cards, one of them as good as the queen.

When the partner takes him out it is either a denial of this normal assistance in the suit named, or it is because the partner has a better bid than anything on which the dealer could hold and bid one trick only. It is with the lack of normal assistance only that we have to deal.

The partner's decision whether or not to deny the suit depends entirely and exclusively upon what he holds in that suit. That is the test for the take-out. The outside strength of the hand has nothing to do with it, except to decide whether the take-out shall be to name another suit or to go to no-trumps. No strength in other suits ever justifies the partner in leaving the dealer in with a suit in which the partner holds only one or two small cards.

It is therefore evident that if the object is to secure the best contract for the combined hands, and the dealer specifies the kind of assistance he wants, the backbone of the combination is the partner's holding normal assistance of the kind named by the dealer.

THE NO-TRUMP TAKE-OUT

When the person dealing starts with a bid of one no-trump, he gives no indication of any suit, but that he holds more than an average share of aces and kings, sufficient to protect or stop at least three suits, as a rule. That is, his strength is scattered, and consists in high cards rather than in length in one particular suit. This clearly specifies the kind of assistance he and the backbone of the combination depends on the partner's holding normal assistance in aces and kings.

Until the publication of the June number of this magazine not a single writer in the world "had made the slightest attempt to discover what this normal assistance should be. Our so-called authorities devoted all their attention to the length or strength of an individual suit that would justify taking out the notrumper making fine distinctions between suits of five small cards or six, but ignoring the thing in which the dealer was chiefly interested, the aces and kings.

THE success of almost every no-trumper depends on the declarer's ability to place the lead in either hand upon occasion so as to lead supporting cards from one to the other, or to take advantage of finessing positions.

If the prospective dummy cannot win a trick or two, he should warn the dealer of that fact. If he is shy of the normal assistance in aces and kings he should deny a no-trumper just as promptly as he would deny a suit in which he had not the normal assistance the dealer expected. In denying suits, the remainder of the hand is totally disregarded. In denying aces and kings the rest of the hand should be equally disregarded. The test for the take-out is normal assistance in high cards.

In the June number of this magazine the first attempt to find what this normal assistance should be was explained, and the results were given. A thousand deals were bid and played in every way possible, the dealer always starting with a bid of one no-trump. The conclusion arrived at was that if the partner held less than four tricks, counted on the double-valuation system, he should deny the dealer's no-trumper, unless he held a singleton or a hand that he was both able and willing to rebid.

THE object of taking out the no-trumper by shifting to a suit is to make some of the cards in the partner's hand equal to aces and kings by designating them as a trump suit, which can stop winning cards in the hands of the adversaries just as effectively as the aces or kings of their suits. A five-card suit, even ten high, is good for two tricks on the average if it is the trump. As part of a no-trumper it is good for nothing so far as giving the declarer any leads from that hand is concerned.

If the test for the take-out is to be regarded as its strength in the dealer's declaration, and that test is applied to the suit, and to the suit only, when the dealer bids on his suit holding, why should it not be equally applied to aces and kings when the dealer bids on his acc-and-king holding?

The importance of being able to get dummy into the lead once or twice in playing notrumpers is matter of too common knowledge to need any insistance upon it here. One example will be enough.

Z deals and bids no-trump. A passes. According to the authorities five small clubs is not enough to justify the take-out, so Y passes and A establishes the diamonds. Now, if Z, declarer, could get dummy into the lead only once he could win the game by making that one trick in dummy and eight in his own hand. Instead of that the no-trumper is set for two tricks, as A leads spades for the end game, after making his diamonds, and Z loses two heart tricks. The club take-out will win five odd and game; simply because dummy can get into the lead and lead clubs, and can trump the diamonds.

THE DEALER'S DILEMMA

The difficulty that all the authorities find with their own take-outs is that the dealer does not know what to do with them. This is because they recommend take-outs from strength as well as what they call "rescues," which arc made on weakness. They recommend a partner to take out with six small spades, or with six spades headed by the three top honors.

Continued on page 108

Continued from page 77

If the partner bases his take-outs on the number of tricks he holds, the dealer is never in doubt. One of the strongest points in favor of this system is what might be called the "informatory pass." If the no-trumper is left in, the partner has at least four tricks in his hand, or he has no fivecard suit with which to deny that number. In either case the no-trumper remains undisturbed unless the adversaries oppose it.

If the fourth hand puts in a bid, the dealer can double if he thinks he can defeat the contract, or if he is willing to force his partner to bid. Otherwise he can pass, and let his partner show his hand, either by bidding, doubling, or passing.

When the partner has normal assistance, four tricks or better, he should pass. Look at these two examples :

In No. 1 the dealer bids no-trump. Second hand passes. So does the partner. Why should he bid two spades? He has four tricks, and in a suit in which his partner probably wants just this assistance. If he insists on spades, in spite of the possibility of the dealer's being weak in that suit, he can bid three, which is not a take-out but a shift.

No. 2 is an example given by Mr. Work as a dealer's no-trump bid. It is obvious that the partner will take it out, as he cannot possibly have four tricks unless he has all the missing aces and kings. If he bids two clubs, the dealer is well able to go back to no-trumps with a certainty of five clubs of any kind in dummy. If the take-out is in any other suit, eight cards between the two hands offer a nice prospect for game.

When the dealer bids a major suit and the partner is short in it, but strong elsewhere, the usual practice is to go to no-trumps. When the dealer is strong enough to go no-trumps originally, why shift to a major suit just because you have five cards of it with two or three top honors? The analysis of a thousand deals seemed to show that so far as games went such take-outs were no better than leaving the no-trumper alone.

ON SAVING POINTS

Many writers seem to argue about the take-out solely from the point of the better chance to go game, ignoring the repeated and continual saving of points in hands that cannot go game, but that can be heavily penalized if not "rescued." A game is normally worth 125 points. It has been shown that if the partner follows the rule of taking out no-trumpers every time he holds less than four tricks, he stands to save an average of 61 ½ tricks a deal. Two such deals are worth as much as a game. Saving games is just as important as winning games, and saving penalties is quite as important as either.

THE GIST OF THE TAKE-OUT

To sum up the whole matter, the theory of all take-outs should be the same. If the dealer bids a suit it has long been acknowledged to be the duty of the partner to deny that suit if he is short or weak in it, because the suit holding between the two hands is the key to the problem of finding the best contract. When the dealer bids no-trump, why should it not be equally the duty of the partner to deny no-trump strength if he has not the normal assistance in aces and kings? We do not take out a notrumper with five clubs to the ace king queen. Why should we do it if the suit is spades or hearts? If the minor suit is very long and strong we bid it, and we bid minor suits at advanced scores, as take-outs. But we overcall such hands. The same opportunity is open under any system. The partner can bid three instead of two as a takeout if he is as good as that.

If the partner holds more than normal assistance in a suit named by the dealer he lets the bid stand, no matter how strong or weak he is elsewhere. On the same principle, if the dealer bids no trump, and the partner has more than normal assistance in high cards, why not let the notrumper alone, regardless of the rest of the hand?

ANSWER TO THE SEPTEMBER PROBLEM

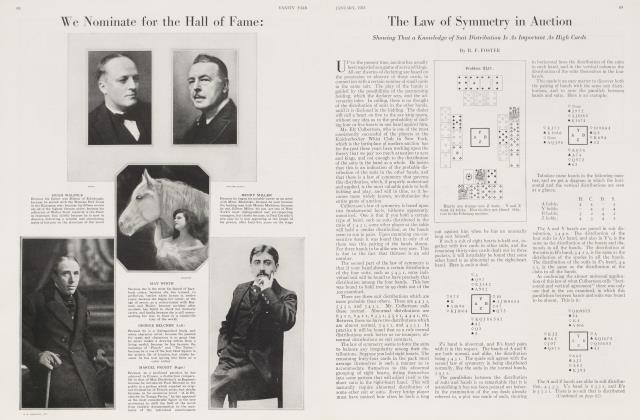

This was the distribution in Problem LXXV:

Hearts are trumps and Z leads. Y and Z want all the tricks. This is how they get them:

Z starts with the king of diamonds, Y playing the nine. Z then leads the three of spades, which Y trumps and leads a trump, picking up B's, while Z discards the club jack. This gives

Y two winning clubs to lead, forcing two discards from B.

If A discards a diamond on the trump, Z makes two diamonds. If he discards spades, and B also discards a spade, so does Z. If B keeps the spades, the diamonds in Z's hand are good. If B lets go the spades, Z will make a trick with the queen, and discard his small diamond.

The original spade lead will not solve, because if Y trumps, draws the trump and leads two winning clubs, B can safely discard both his spades, A having discarded a diamond.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now