Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Crowd and the Golf Champions

The Part Played by the Followers in the Defeat of Macdonald Smith at Prestwick

BERNARD DARWIN

THERE has been, on both sides of the Atlantic, ever since the British championship at Prestwick, so much discussion, explanation and uneven temper because of the treatment accorded to Macdonald Smith, by the crowd that followed his match, that I think it may be of interest to hark back a little and review the facts and circumstances.

To begin with, it is not quite fair to say that the crowd prevented Smith from winning the Championship; not fair at any rate, from the point of view of Barnes, who played splendidly, and was an entirely deserving winner. Everybody has his own opinion, and mine is that if Macdonald Smith could have played his last round in decent comfort, he would in all probability have won. But I must deny that he certainly would have done so. The fourth round is a terrible strain for any man, particularly for a man with a lead, when he secs the strokes beginning to slip. And they could slip—oh! so easily!—at Prestwick, on that hard, yellowish turf, looking more than ever glassy and glittering in the sunshine with a good strong northerly wind blowing, and blowing towards the Pow Burn of evil fame.

SMITH had to do a 78 to win and a 79 to tie. What is sauce for the goose is sauce for the gander, and if Barnes could take 79, as in fact he did in his third round, Smith might have taken 79, or even more, for his fourth. There is no man breathing, so good a golfer, or so immune from the terrors that attack golfers, that it was certain that he must do 78 or better. He might well do so, but then, as the Chorus would remark in a Greek Tragedy with their admirable banality, he might not. Personally, as I said, I think that Macdonald Smith would have done it had it not been for the crowd, but beyond italicized "think" I will not go.

There is no doubt in the world that on a day, whereon everyone suffered from the crowd in some degree, Smith and his partner suffered the most severely. He was the leader; he was by birth a Scot whereas Barnes is by birth an Englishman, and a Scottish crowd is nothing if not patriotic; he started his last round at twenty minutes past three o'clock, while Barnes had begun his last round at half past twelve, about the hour of lunch. All these three factors went to make his crowd the biggest of the day, and it was a crowd.

There are always tremendous crowds on the West Coast of Scotland. There had been one, only a few weeks before at Troon, to see Miss Wethered play Miss Leitch, and it is noteworthy that, despite of it, those two young ladies played the most wonderful golf. There had been another at Prestwick eleven years ago, when Vardon and Taylor the two leaders, had been (by the ill fortune of the draw,) paired together on the last day of the Championship. Taylor had not forgotten that memorable day and, before this year's Championship began, he prophesied that the man who was leading with one round to go would not be the Champion. But I think all these other crowds "paled their ineffectual fires" before the one which went racing and chasing, squeezing and jostling after Macdonald Smith and his partner Tom Fernie. It was a friendly, good-tempered crowd. It had no vice, save that of numbers, but if it wanted to get out of the way it could not.

AND not only was there this huge moving crowd, but there were temporarily stationary crowds. They crowned the top of every tall sandhill, of every little bank or brae, and as the main body came along they .charged from their heights to plunge into the throng, causing great ripples and eddies and waves as they poured down. The stewards at Prestwick know their work, and did it valiantly, but nobody in the world could have prevented the long nerve-racking waits while the course was being partially cleared. The short shots to the hole from the edges of the green had to be played down very narrow avenues. The ball had barely time to reach the green before the avenue had closed up and vanished as if by magic. As to the player he had no hope. He and his caddie were swallowed up, only to reappear when the stewards had once more done their task.

As I said before everybody "as is anybody" had a taste of this sort of thing. Barnes always ended with a big crowd, but as, by the luck of the draw, he began his first round at 8 o'clock in the morning, and his second at the lunch hour, he had at least some clear time. Moreover, his crowd, at its worst, was never so big, so unmanageable, so rampacious as was Macdonald Smith's. It is wholly impossible to estimate in strokes the disadvantage of playing under such conditions as these. It is quite conceivable that if Smith had not just let one stroke slip at the third hole, and another at the fourth (where a very nearly good shot of his was trapped) he might have played as well as ever he did, played actually all the better for sensing the encouragement of that great band of people. But the conditions were such that, if once things went a little bit wrong and the player began to think about the crowd, then he was likely to go a great deal more wrong. In short they were not—and this applies to all the competitors—conditions under which a golfer can be expected to do his best. Prestwick is a great course, a great home of popular golf and the original home of the Open Championship, but it is not in its formation well adapted to a crowd, and it always has a bigger crowd than any other course. And so, though it is sad to think of no more Championships there, I fancy that for the future we shall have to look to the emptier places of the earth for Championship courses.

IT is a sign of the changing times that this is almost the first occasion on which a popular golfing idol has been destroyed by his own popularity. I remember that not so very many years ago, the illustrious obscure who had no crowds used to complain of those that the great men had. It was not that they were jealous of the attention paid to others rather than to themselves. It was not that they themselves had to contend with the back-wash of somebody else's crowd in front, which sturdily refused to recognize any other players on the course, save those whom it was honouring with its attention. They said that the crowd was a definite advantage to the players whom it watched. And there was a good deal in it. No man who can command a crowd will ever lose a ball. No matter how erratic his shot there are hundreds of pairs of eyes to spy the ball, and hundreds of pairs of feet to stumble on it. Then how often has a body of spectators, declining to stand far enough back, prevented a ball from running over a green or into a hazard? In putting too, the crowd can help the player a good deal in shielding him from the wind, and to a less extent this applies to all the other shots.

But, in order to be a help and not a hindrance, the crowd must be just so big and no bigger. Once it gets beyond a certain size it cannot, or it will not get sufficiently far out of the way. It will indeed leave a certain open space in a straight line between the player and the hole, but it takes no account of the wind or of the lie of the land. If the player wants to play far out to left or right in order to avoid a particular trap, or to let the ball swing with the wind, or to use some particular bank, "not all the king's horses and all the king's men" can make the crowd appreciate that fact. They will allow the poor man his straight road, but they have no sympathy with "fancy shots". If all the people who go to make up a golfing crowd, were properly sane, docile and virtuous, and understood the game thoroughly, no doubt they would not be half such a nuisance as in fact they are. If only, for instance, they would not run, but they will. The first to do so is generally a small boy. I remember Mr. Wethered telling me that his first recollection of watching a professional match as a very eager little boy is that of being severely reproved by Mr. Croome for this heinous offence of running. Once one boy has run it is all up. Even if the boy could be captured and smacked it would be of no use. The germ of running has infested the crowd; run it will and posts and rails and ropes (of which by the way there were plenty at Prestwick) will not hold it.

Continued on page 106

Continued from page 82

There is another respect in which a crowd is highly exasperating. How many times has one heard some perspiring steward lifting up his voice with the sweetly reasonable words "You'll all see much better if you make a big circle" and how seldom have we seen him obeyed. There is always some one black-leg who disregards Union principles, because he thinks he can gain an advantage for himseff, and then again it is all up. There are some putting greens which are in natural amphitheatres, so that it is obvious common sense to remain on the surrounding high ground. But will the spectators do so? Not a bit of it. Just one tiresome being sets the example of getting down on to the verge of the green itself and then, like so many insane sheep, we all rush down after him. "Players be d—d, I've come here to see." We do not all say it quite so bluntly as did that Lanarkshire miner at Prestwick, but I am afraid we are all a little inclined to act on his principle.

There is one advantage in a big crowd, and that is that it cannot move if it wants to and the player's eye is not suddenly distracted by a movement behind him. That is the trouble of the humbler golfer, at whom the spectators only cast a casual glance as he goes by. It is he who suffers from some very particular idiot who darts forward at the critical moment. The big crowd does at least stand still.

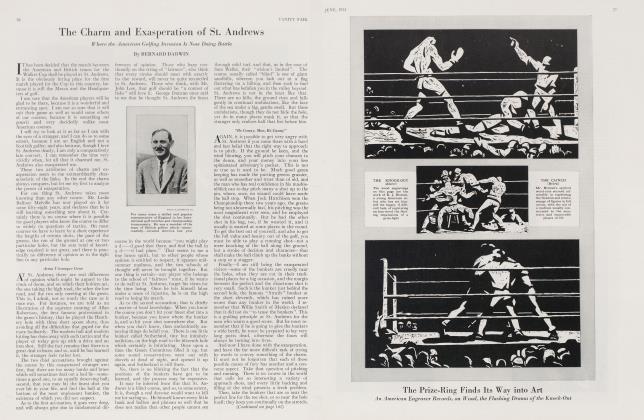

Finally one ought not to rail too bitterly against crowds, if only because they are so picturesque. There is something wonderfully exciting in the tramp, tramp, of their feet as they start off with their favourite; wonderfully impressive in a big silent ring round the green. Shorn of this familiar setting, a great match at golf would lose much of its dramatic quality. The players would, I am sure, miss it themselves, for if the crowd can distract, it can also inspire. Some of the greatest golfers have always loved a crowd, and I think the crowd has known it and loved them in turn. This does not mean that they are self-conscious, for nobody who is that will ever consistently do himself justice in the public eye; they can concentrate their attention on the hitting of the ball, but subconsciously they thrill with the feeling that people are looking at them.

At any rate, whether we like it or not, the golfing crowd has come to stay. Up to a certain point it can be controlled; beyond that point it cannot and I suppose we must recognize that fact and try to choose our battlefields with a proper mixture of sentiment and practical wisdom.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now