Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe American Distaste For Opera

The Reaction of a Basically Unoperatic People Against Its General Artificiality

GILBERT W. GABRIEL

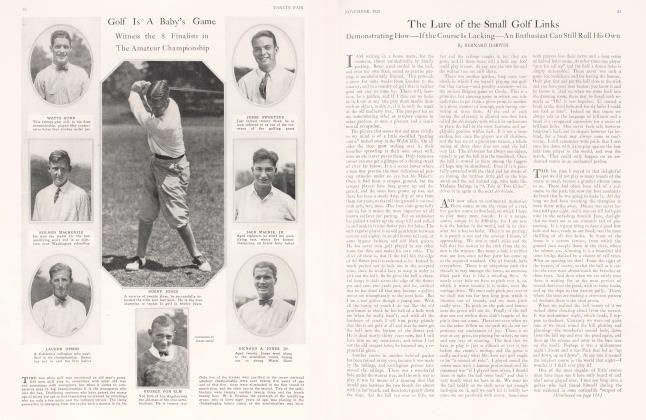

AMONG the questions historians are not bothering to settle is: which was discovered first, grand opera or America? Quite independent of the findings of Columbus, it would seem that the Italian musicians of his time were engaged in evolving a strange, stately but inherently foolish mixture of those arts which added together constitute grand opera. They paid no attention whatever to the rumor that, beyond the utmost oceans, some fabulous land had been found which would never be vastly interested in their concoctions. An unoperatic people would be a worse than cannibal people to them.

It is all very well to point to statistics and balance-sheets. Neither these nor the fervid bally-hooings of a Music Week will ever convince America that it loves grand opera. It is true that the few opera companies and travelling troupes we have here are sometimes independently successful—but they are few, indeed. Opera has passed from the state of a sport for the fashionable minority to that of a duty of the small, solemn majority. A great many more Americans have come to know a little more about opera in the past few years, and to like it less.

THERE is such a thing as a naturally operatic people. We are not. We are so far from being one that, when foreigners accuse us of precisely this grief of not being an operatic people, we scarcely know what they are talking about. The only way to learn is to live in an operatic country. The genuine Berlitz. method of learning what is an operatic people is to try to sleep in any Italian city on a hot summer's night. By the time you have been awakened out of your fourth nap by the dulcet but fervid whoopings of Rigoletto on one street corner and Trat'iata on another, while strains of Lucia and L'Elisir d'Amore drift incessantly over the tiled roofs of near and far, and the dawn comes up to any odd number of amateur renditions of Celeste Aida . . . then, and only then, you will know the full flavor and meaning of an operatic country.

Germany, in a more phlegmatic style, will give you an equally explicit definition. You will not have to wait for the so-called festivities of Bayreuth to be treated to Die Meistersinger in all the patient magnificence of its original length, or to heap the score of Tristan expounded with each and every soliloquy left alive, the audience munching rolls and slices of ham during the stealthy lighting of the garden scene, the whole house grim and stoic, languorous to the exuding point, against the long Wagnerian siege. This, too, is a dreadfully operatic people. If you doubt it, sneeze once during the half-hour of King Mark's lament.

So, in their more impulsive fashion, are the Cubans, Mexicans and South Americans a lit and naturally operatic audience. We never dream of bellowing praises and denunciations at the singers, as they do. We have not that blessed faculty of ignoring the thousand and one small vocal and dramatic mishaps which seem bound to break out of the seams of any performance of grand opera. When a singer goes severely off the pitch, he makes Americans miserable. When a soprano indulges in that wabbling of the throat which is supposed to be exceedingly bad form among purists, she afflicts and embarrasses us. That is because we fail to accept opera as a passion beyond sense or sensibility, temper or taste. There is no nibbling at opera. Gayly as the Italians, heroically as the Germans, as uncritically as the Cubans, you must swallow it whole, burrs, blossoms and all. Which we do not.

OPERA is often sublime and always absurd. Never the one unless you can forget that it is also the other. The very notion of drama squirming in the hot press of music is strange and slightly silly. It exasperates dramatists and affronts musicians. Theonly interested party who cverexprcssesconsiderable satisfaction over grand opera is the scene painter. Me is permitted to make bigger, if not better, scenery. The public at large—the American public, that is—has no pet aversions or inhibitions to solve. It simply, in that same way whereby it secs the pistol smoke before it hearsa distantshot, senses the absurdity of opera before it realizes the sublimity.

An art made up so complexly of so many parts has to have a multitude of rules and traditions for its guidance. A thousand and one small dicta of musical scoring, libretto custom, stage deportment, have not only to be accepted and honored; they must likewise be taken humorlessly for granted. Interminable farewells, long, lusty perorations in honor of la fatria, love passages whispered with the fury and finesse of a steam calliope, are formalities which opera cannot toss off, and which the shirt-sleeved impatience of the American temperament cannot forgive. The coloratura cadenza into which every sel f-respecting heroine of Italian lyric drama is supposed to break at the innocent moment of glimpsing her shadow on the grass, or of hearing a nearby temple bell, seems to us merely a musical rabies. We shall never quite comprehend why all the beautiful young victims of insanity have to burst down to the footlights in nightgowns and vent their madness on flute obligatos. We shall never wholly understand why two or three gentlemen in tights cannot gather together without exploding into a drinking song or a conspiracy.

BURLESQUES of opera are almost as trite, these Chauve-Sourisian days, as opera. The easiest parody possible to vaudeville mongers is the horseplaying of a grand operatic spoof. From Addison's elegant times to D. H. Lawrence's, authors have had their fun at the expense of the conventionalities and incongruities of opera. That these are so obvious, and curry such cheap jibes, is first and finally the fault of opera itself. At least it is plain that Americans think so. We sniff alike at the light-headed vocalists of Bellini and those creatures of Wagnerian epic whom Jean Cocteau apostrophized as "militant washerwomen".

All of this genera! dissatisfaction crystallizes into several definite charges. Opera, to begin with, suffers from bad plots. It is a truism oft retold from Chicago to Cairo, wherever opera is housed, that the worst plays make the best librettos. To bear up under the tardiness of arias, the floridity of choruses, a plot must be either wholly naive, wholly coarse or wholly preposterous. Try to revive today Le Rot S'Amuse, the Victor Hugo play which gave Verdi his most famous libretto, and see what happens to the audience. Olga Ncthcrsole once played in a spoken version of I. Pagliacci, and it was almost dreadful. When, just after the war, the Metropolitan Opera House made a few palaverous attempts at translations of Wagner into English, we began to realize that even these titantic poems are sometimes pretty poor offeringson thealtar of music. Even Wagner, inspite of all his pronounciamentoes to the contrary, could not make drama the primary object of opera.

For, when all's said and printed, it is the composer who rules this operatic roost. And composers are notoriously bad showmen. They accept any hack's libretto because it can be set to music—to their own particular school and sort of music—and not because it will attract a public on its own account. Having once accepted it, they enjoy the immemorial privilege of fattening it here and thinning it there for the purposes of their composing. Puccini was the one Italian exception. He made his operas out of swift, popular and not too appalling plays. And he saw to it that his music would not interfere with those attractive attributes. In short, it can be done—and can be appreciated. Puccini, whatever you may hold against his music, is the best liked composer in America. He never demanded that we take, along with his tunes, such flamboyant, gruesome and inhuman nonsense as L'Africana or La Juive.

WHICH brings up another characteristic of opera repugnant to Americans. It is so tragic—so loud and long and tragic. Enough heroes die of wounds and broken hearts to make a whole Italian army corps. Enough heroines throw themselves suddenly and unexplainably down upon their lovers' corpses with expiring thrills to populate Naples twice over. Death is the maudlin ecstacy of innumerable recitatives; all means and modes of it, from the last stages of tuberculosis to the writhing agonies incited by munching on the poisonous leaves of a mancinilla tree, arc celebrated by grand opera with a gusto which neither love nor rescue, wine nor vengeance can arouse. We have a little too much respect for death to bandy arias with it or risk such fulsome salutations on it.

Foreigners expostulate, all these minor difficulties are washed away in great music. That is another discomfort of grand opera. Its music is so great. One's cars have always to be on their best behaviour. One feels like the housewife of a genius, lives on the edge of one's seat and listens in awe. The classics are cold acquaintances, especially after their majesty has been crowned with centuries of repetition and familiarity. What thrill is to be extracted now from La donna e'mobile except the foregone realization that it always was and always will be a famous song for famous tenors?

(Continued on fage 110)

(Continued from page 68)

This, in turn, suggests the mortifying topic of tenors and other such personal impediments to a genuine enjoyment of grand opera in cis-Atlantic quarters. Perhaps the sharpest pang an opera house can endure is encased in the shapes of its singers. The mere accidence of a lovely voice drives out in front of the footlights some of the queerest, fattest, most awkward and antagonistic figures ever perpetrated on the human race. Romeos and Parsifals swing their huge, barrellike, vibrating anatomies before them, unashamed. Mint is and Matrons, wasted away to slightly less than two hundred and fifty pounds apiece, outweigh all possibilities of romance. One of the great drawbacks of singing is its seemingly inevitable instigation of adipose. He who masters his diaphragm for vocal purposes becomes its slave, thereafter.

But, flesh and fat aside, opera is handicapped in other ways by its singers. Or perhaps the singers are handicapped by opera. It is not for audiences to decide. Audiences only know that great, or even agreeable, actors are rare in the largest opera houses. Chaliapin and Jeritza are better known for their acting than for their voices; best of all they are known for their good looks. They are exceptional. The usual opera-goers have been bullied into accepting fifth-rate acting from first-rate singers, and will put up with an unwieldy and unmeaning code of stock gestures and full-fronts. Try to discover on the operatic stage one artist natural enough to stand, even when not singing, at profile to the footlights. Try to fathom the frequency of that one, universal fling of arms upward and chest outward which greets the mention⅝of God above or Mother Earth beneath.

Had we any native operas, we should soon develop artists enough to sing and act them in our own native style. That is another cause of our unwillingness to take opera to our >'nmost hearts. It is foreign in its tongue, its backgrounds, its characters, in everything. When Americans begin to write good operas we shall begin to love them. And, of course, until we begin to love them they will not begin to write them. At any rate, so they say. Meanwhile they go on the smaller assumption that all good American operas will have to be about Americans, and all better ones about Indians. You can't expect us to become greatly excited about Indians at this late date, even when opera paints them exceedingly red.

But, of course, the most immediate objection to grand opera in America is the dress-suit complication. It has come to be regarded as a fashion show, a social contest; over it, a white and rigid ghost, stalks the great American bugaboo of the full-dress-shirt. And now that the glamour of exclusiveness is out of it there is no heart left beating behind the shirt. Naught but the uncomfortable realization that although opera (in the words of the most successful impresario in the land) is a silk-lined social event, the burghers who attend its premieres and revivals nowadays take no such relish in their privileges as of yore.

It is terrible to suspect that the opera managements are trying to undermine America's one proud contact with opera, and to force us into watching the stage and listening to the music instead. An absolute impertinence!

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now