Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowSex Plays and Noel Coward

How a Self-Conscious Playgoer May Become an Advocate of "Clean Drama"

A. B. WALKLEY

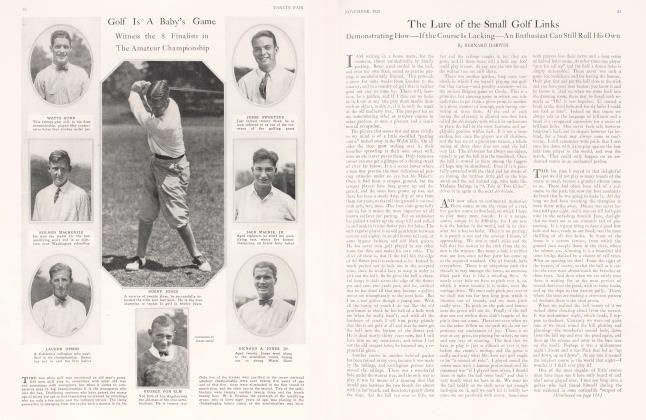

EDITOR'S NOTE: Noel Coward, the subject of this article by A. B. Walkley, the eminent critic of the London Times, (who will, from now on. be a regular contributor to Vanity Fair), is a young English playwright. Mr. Coward is the enfant terrible of the English theatre; regarded as a master of the double entendre so necessary to the sexplay. With Fallen Angels produced in London last season, Mr. Coward's precocity provoked a storm of critical protest. His name became thereafter a synonym for "shocking." He is the author, also, of "The Vortex", and "Hay Fever" these plays already being known to America; Mr. Coward not only writes plays, but acts in them. He is the concocter of several revues, and has perpetrated innumerable popular jingles. "The Vortex" is a New York success.

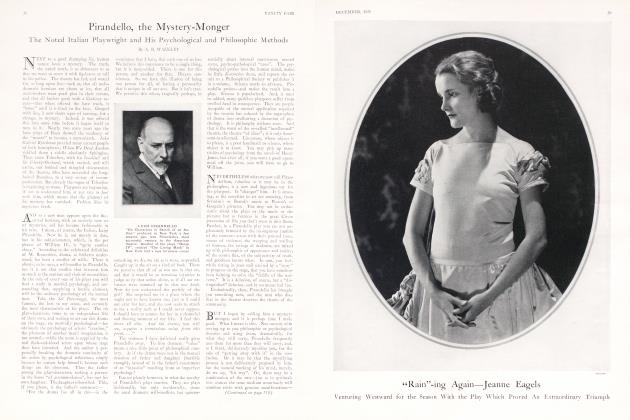

MR. NOEL COWARD will not, I know, feel aggrieved at my association of his name with this burning topic. He is no sensualist, either of the metaphysical type, like Signor Pirandello, or of the slyly innuendoish type, like Mr. Somerset Maugham. These writers take sex, as other people take pills, with a wry face. For them it is sexual passion, a natural force let loose. For Mr. Coward it is just a good joke, a new toy. In other words, Mr. Coward is a quite young man. Anatole France, it would appear from a book of recent revelations, declared love not to come by nature but to be a difficult art, which it took a lifetime to learn. Only men over fifty and ladies over forty-five could hope to be proficient; as amorists, the young were negligible. Naturally enough, thus, Mr. Coward assimilates sexual love as he assimilates every other parcel of experience, from the "modernity" of Chelsea to oeufs sur le plat Bercy, with the healthy omnivorous appetite of his age. As a born dramatist, eager to cram every scrap of his experience into the form of dialogue and scene, sex seemed to him a subject like any other, but that was his mistake.

SEX, he was soon to learn, is not a subject like any other. "How, Sir, do you sac 'good fellow' in print?" asked an obituarywriter in Printing House Square of the great Delanc, and was answered "Sir, you should not say it at all." There arc many austere persons to whom sex is not a subject at all. By "subject", I. mean of course anything in nature that is represented in art. Among these natural things, why not sex, the most important of them all, the most vital to the race, the governing factor in the scheme of life? Logically, the obvious question seems to admit of only one answer. But logic is powerless against inherited and ingrained prejudice and there's no blinking the fact that many millions of the earth's population are thus prejudiced against the presentation of the sexual instinct in art. Why? "Ah, why, Ernest" says Mr. Frank 'Finney to his friend, the music conductor, "I'm getting deep," and I feel I'm getting deep when I must approach this tremendous question. The easiest way, and therefore, the one usually taken, is the ethnological. It is a matter of North and South, or else, East and West. "Anglo-Saxons" generally are against "Latins" for sex as an art theme. The gulf between East and West on this subject is revealed by the contrast between the literal translations of the "Arabian Nights" by Burton or Mardrus and the bowdlerized version by which they were first made known to the Occidental world . . . But enough of ethnology! I shrink, Ernest, from getting too deep and finding myself out of my depth. Let me try a new dichotomy. Does it not all come to this? That there are two opposed states of mind on the question of sex in art, which one may call the "hick" state and the sophisticated state.

THE "hicks", I understand, inhabit the middle west of North America, and, incidentally, their views control not only the fortunes of the "movies" but the election of Presidents. But the "hick" state of mind has much more than a local interest; it may be found all the world over. No doubt there is more of it in the United States than in Great Britain, more of it in Scotland than in England, more in Stow-on-the-Wold than in Piccadilly, Be. it is unevenly distributed over the surface of the Planet Terra. But "with such a being as man, in such a world as the present one", it is nowhere far to seek. More than that, everv man Jack of us, I think, has a touch of the "hick" in his mental equipment. He may hide it, he may loathe it as the very devil, but there it sticks within him, a malignant disease which he cannot extirpate. It hates novelty, it hates surprise, and without surprise there can be no art—whose essential function it is to startle us into a new observation of the external cosmos and to give us a glimpse of the World as Reality, underlying the World as Appearance—it is when confronted by unfamiliar art that the "hick" within us leaps up and shrieks that it cannot bear it. I do not remark any new development in the art of the theatre that has not been received with howls and execrations. The plays of Ibsen, when first seen in London, produced something like a state of Civil War. Nothing but the fact that, outside Italy, Italian is an unknown tongue saves Pirandello's bacon. So it is with new music (or "noise") and new painting, (called by' Ruskin, one of the most hick-ridden of men, "throwing y'our paint pot at the head of the public") and new architecture (or "sky-scraping"). Turn to literature and you get the same old story. We know what Johnson said of Sterne, what Jeffrey of Wordsworth, what Henry James of Thomas Hard. . And I confessed to having been knocked endways by M. Brousson's recent revelation in Anatole France En Pantoufles that A. F. professed "not to understand" Marcel Proust and to find Bergson incomprehensible. Proust is, I suppose, the most daring of all innovators in the art of the novel, as is Bergson in philosophy. They take, I admit, a good deal of understanding; but most of us humbler folk find the effort well rewarded. But France's "hick" offended by the new and strange, refused the effort. The "hick" triumphant in an Anatole hranee! Doesn't that drive home my point about the ubiquity of the beast?

IF this is the attitude toward new art of the sophisticated mind, with its ever persistent taint of the "hick" mind, what is to be said of the "hick" mentality pure and simple? In the first place, I doubt if it recognizes art at all, as such. It knows only the practical activities of the human spirit and wholly ignores the theoretical. Hence, it automatically substitutes ethical judgments for aesthetic; it has no category of the "beautiful", but only ol the "moral" and the "immoral". Because nudity in practical life is something indecent, something demanding the interference of the police, it puts a fig leaf on the Mcdicean Venus, bowdlerizes Shakespeare and turns the Song of Solomon into an elaborate allegory. It is, in the Gallic idiom, as "ignorant as a carp" and as happens in other savage tribes, is the victim of a kind of devil-worship, or cult of the harsh and cruel, which is euphemistically termed asceticism.

But why go on' We need no analysis of the "hick" state of mind. For have we not all seen its advertisements round us in the defaced statues and smashed windows of our Gothic cathedrals, in the deliberately hideous bonnets of our Salvation lasses, in the ghastly imbecility of the "movies", and in the novels of M. George. Ohnet and Miss Ethel M. Dell? Art new or art old, it's all one to the hard-shelled "hick"! He has "no use" for it. Further, he is in mortal terror of it, as a snare for his sensuality. For, almost invariably, within the ignorant, unworldly, sex-repressed man, there lurks the fierce sensualist, as is it not a familiar commonplace that sex repression inevitably leads to sex obsession? Nature takes her revenge. The visions of St. Anthony have a simple physiological explanation. Thus, the "hick" loses all poise at a sex play. Listen to the loud smacking of the lips and the hysterical tittering in the gallery, whenever the most innocent kiss is exchanged on the stage. Two kisses and he will hiss! His moral susceptibility has been outraged and he will go home, angrily protesting against the "dirt" of the spectacle and clamoring for "clean drama".

(Continued on page 96)

(Continued from page 47)

The worst of it is, he supplies a "slogan" for the better Press, which sees an opening for a "stunt". The chastity of our more vulgar newspapers is one of the marvels of the age. The simple truth is, they know which side their bread is buttered, for they circulate among the "hicks". The last thing these readers want is dramatic criticism—as they don't know what art is, how on earth can they be expected to know what criticism of art is:—but "slogans" and "stunts", "crusades" and "campaigns" are the very meat their souls loveth, and their Press sees that they are duly catered for. This is what seems to have happened over Mr. Noel Coward's unpretentious little play Fallen Angels. He says it reduced "the daily Press" (too wide, I can answer at least for one exception) "to a pulp of shocked exasperation" and to a shower of abuse. "Disgusting", "shocking", "nauseating", "daring", "outrageous", e •via dicendo. I am not a bit surprised. Calling names is much easier than critical analysis, easier writing and easier reading. And then it is always "safe to be shocked," especially for the critic who is not quite sure of himself. It suggests a more delicate moral susceptibility, a higher standard of conduct and (in journalists) a more public spirited concern for the social welfare. Further, it is sure to please the Editor, who knows that moral indignation is one of the most profitable lines to exploit next to the craze for cricket in the summer and football in the winter. Mind, I do not say this is a conscious process: there is no organized conspiracy between editors in their dens and their appointed representatives in the theatre. It is simply in the nature of things. Both parties indeed are of a rare innocence, much more rare than a vain people supposeth. It is the business of editors to understand golf, partisan politics, the business of statesmen and the vicissitudes of the public taste in ephemeral reading, but of the real world, which in Victorian days used to be called the Book of Life, especially of the secret volume which Balzac says is composed of what men utter in smoking rooms and women whisper behind their fans, they arc profoundly ignorant. They cannot spend their evenings in the theatre, "being otherwise engaged, Mr. Boffin", and send in their place a recognized expert. Poor, dear innocent! How can he be expected to know anything of the world? From his early college days he has been a cloistered student; he is more familiar with the minor Elizabethans than with the buying and selling, flirtingand fox-trotting, polvgamous and polyandrous, bobbed and shingled crowd of Georgians, jostling one another outside his study. True, lie secs this crowd as in a glass, darkly, reflected, that is: the mirror of the stage, as the prisoner in Plato's cave saw, projected on the wall before him, the vague shadows of the real people without, and remarkable ideas about the modern world he must get to be sure—how mistresses tell their butlers "That will do, Parker" or their parlour maid "You may leave us, Jane" or offer "Thanks, a thousand thanks" or decline with "No, a thousand times no", • or spend the whole morning alternately patting cushions and arranging flowers, and how M. Duval, pere resolutely keeps his hat on in the presence of la dame aux camelias, and, generally, how the people of today naively retain the manner and customs of their grandfathers and grandmothers! But the poor, dear innocent swallows it whole, and is duly "shocked" when he sees Mr. Coward's young wives cynically discussing their prematrimonial amours—(Julie: "It seems so unfair that men should have the monopoly of Wild Oats." Jane: "They haven't really, but it's our job to make them think they have...." Oh, fie!) and drinking between them a whole bottle of champagne.

It is the "hick" within him that is shocked and starts calling names. This internal monitor is as tyrannical as the Socratic daemon. Knowing not art, it cannot distinguish theme from treatment, subjective mood from objective fact, frivolity from grossness, fun from sin. In a playful fingering of one of the innumerable strands of modern amorism—that elegant and complicated pattern which humanity through the ages has with patient ingenuity woven over the crude background of physical action—it sees only salacity. Thus man is forever trying to decivilize himself and to get back to the primeval forest. It is a spectacle which the Gods on Olympus must find infinitely diverting. And even Mr. Noel Coward, I think, can afford to laugh—of course, in his sleeve.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now