Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Position of Shakespeare

How the Public Sustains Its Interest in the Classic Dramas Through Tradition

A. B. WALKLEY

(Critic of the London Times)

MUST our judgment of literary classics be always tainted with hypocrisy? It would seem so. The force of public opinion is too overwhelming. Private opinion hasn't a dog's chance. To fight seems almost an act of impiety, a flying in the face of Providence. Nor is to conform mere pusillanimity. Imitation is the strongest bond which holds human society together; we follow the fashion, partly to avoid the trouble of inventing, like the White Knight our own hates, but much more because we like it. It assures us of our congruity with the scheme of things, tells us that we, too, are entitled to our place in the sun, and fit as neatly in the procession as our neighbours. This herd-instinct, as the professors of Collective Psychology rather impolitely call it, is peculiarly strong where literature is concerned. For then private opinion is not so much powerless as "full of emptiness." It could not formulate an aesthetic judgment of its own even if it dared. It supposes the others know. So do the others. Hence a "vicious circle," surrounding a point which, in more than the Euclidean sense, "is without parts or magnitude." And so we go on, writing more Lives of Shakespeare, to prove that the plays were not written by Shakespeare, but by another man of the same name, and unearthing more portraits of Shakespeare, obviously portraits of the same bald brow and pointed beard but of entirely different faces, and erecting statues of Shakespeare in Leicester Square and on the Paris Boulevards which agree only in the remarkable indications that Shakespeare could read by merely leaning on his elbow without looking at the book. And we even go on re-exhuming—if not always reviving—a select few of his plays, generally the same select few, which we go on seeing over and over again until we all fancy we have learned them by heart—ah, bien entendu, save the actors, who have tried and know it's not to be done. But if these knowing ones more often declaim their own "gags" than the authentic text, the roll of the blank verse carries us along, just as we fox-trot to a Jazz band even though the saxophone caterwauls a note or two out of tune—and we are just as happy. We have conscientiously performed a quasi-religious rite. We have been worshipping at the shrine of Shakespeare.

We go on, I say, but the statement needs qualification. We go on in the long run. We go on, taking us by and large. The fact is, our devotion has begun slightly to flag. I have really been carrying my mind back to the Victorian age. Today—and Oh! what magic there is in that one word: it connotes the day when you and I are alive, when her kisses are still lingering on our lips, and the scent of her hair still clings, when our heads still slightly ache, while "sermons and soda water" make our regrets a shade more poignant. The day, when our pulse beats more quickly to all the pomps and verities of this wicked world, the day that is an infinitesimal (but exquisitely precious) point between two infinities, the day wherein we are tingling with the consciousness of reality, and responding to the warm pressure of it—well, today, the axis of the world has somewhat shifted. What is humorously called the spread of education, that is to say the advent of a new population prone to question the wisdom of the old and to criticize the antique shibboleths, has to some extent affected the position of Shakespeare. There has been no open revolt. That would have been unpatriotic, for the Shakespearian cult is still a part of patriotism. (In the great war, the Teutonic claim to understand and like Shakespeare better than did his own countrymen, exasperated the said countrymen even more than the Hymn of Hate). It is rather with this as with other religious beliefs: They do not yield to controversy but are found one fine morning silently to have fallen away. The glamour of Shakespeare's name has gone. His prestige is sensibly diminished.

I DO not pretend that the advent of a new, half educated, skeptical population wholly accounts for this. What else? Partly, I think, the fact that Shakespeare has been a compulsory ingredient in the new system of education. Shakespeare the grammarian, the refutor of etymologies, the contriver'of uncouth archaisms, to be "paraphrased" into modern English, has been the mortal enemy of Shakespeare, the poet and playwright. It has been the same story, in our older Public Schools, where the Greek Tragedians used to furnish lessons in aorists and verbs in m. If 1 had a grudge against any classic author, and wished to get him thoroughly hated, I should say, turn him into a school book. Every healthy minded school boy loathes those fragments of literature that are foisted upon him in his class books as models of "English Composition", to be copied out, learnt by rote, "parsed", and the Lord knows what. The Bible has been spoiled for many years in this way, and we discover, years afterwards, that the 1611 Version is really a fine old piece of Jacobean literature.

If the scholastic misuse of Shakespeare has been a great deterrent to the artistic appreciation of him, so, I think, have been the labours of "scholars" of another sort. I mean, of course, the Shakespearian scholiasts, analysts of texts, dominants, syllable endings and handwriting, in short the born Dryasdusts, who, like the Elementary School Masters, have studied their author as an historic "document" rather than as an aesthetic fact. 1 should be the last man to depreciate the performances of men like Sir Sidney Lee, whose Life of Shakespeare is a noble monument of erudition and sober, sagacious criticism. But when we think of the tagrag and bobtail of this tribe, the cryptographers, the Baconian heretics, e tutti quanti—faugh! They are the worms who have fattened upon the unhappy poet's corpse. So true is it that taste is as rare as genius, and that genius is the natural prey of the tasteless.

FURTHER, I am old-fashioned enough to believe that the decline of Shakespeare has gone hand in hand with the rise of the cinema. Their methods are so diametrically opposed. Their respective appeals are so different! How can a story which is all poetry and rhetoric, which is remote from all modern experience, a story for the trained ear and the informed mind, compete with one that "tells itself" to the naked eye and in the twinkling of an eve, that is not merely modern but (I apologize for the horrid phrase) "up-to-date", and that, for the cumbrous language of words (and many of those words obsolete), substitutes the sharp, instant significance of pictures? As well recommend a diet of roots and herbs to one who has tasted peptonized extracts! Crabbed age and youth cannot live together. There is not room at once for the humour of Falstaff and the humour of Charlie Chaplin. The judicious, you may say, will take care to enjoy both. True. But begin with Charlie Chaplin, and what then?

Briefly, Shakespeare in London is no longer a "live proposition." There are stray hole-in-corner performances of him, no doubt; but these do not jeopardize the general statement. "Shakespeare," said Dr. Johnson, "never has six lines together without a fault. Perhaps you may find seven, but this does not refute my general assertion. If I come to an orchard, and say there's no fruit here, and then comes a poring man, who finds two apples and three pears, and tells me, 'Sir you are mistaken, I have found both apples and pears', I should laugh at him: what would that be to the purpose." Practirally, Shakespeare has disappeared from our stage. I say practically, to save myself from the "poring" man. The great busy mass of Londoners who go to the theatre for enjoyment, do not ask for Shakespeare, and, accordingly, are not supplied with what they don't demand.

Continued on page 132

Continued from page 43

There were, to be sure, two revivals of Hamlet during the past season, but in neither of them was the poetry, the mystery of Hamlet the attraction. One was a rather childish experiment: Hamlet "in modern dress". People went to see how odd the Prince of Denmark looked in plus fours, and Polonius in a frock coat. When managers seek to draw the public to Shakespeare by presenting him in masquerade, they are plainly at the end of their tether. The other revival was for the beaux yeux of an American actor, Mr. John Barrymore. But Mr. Barrymore was the attraction, not Shakespeare—Mr. Barrymore and the fair "extra" ladies who figured as nuns at Ophelia's grave side, and about whom he told a story too good to be lost. He had reminded them at rehearsal that they had to look like virgins, to which they replied, in some confusion, that they had been engaged as extra ladies, not as character actors. My statement that Shakespeare is no longer a live proposition still holds good, in spite of a successful revival of Henry VIII wherein the true Shakespearian "purple patches" competed hopelessly with the crimson and gold patches arranged by Mr. Charles Rickets, A.R.A., after Holbein. Again the attraction was not Shakespeare but the spectacle. "The water from the Temple fountain," said Charles Lamb, "makes a fine, refreshing drink—if blended with a little gin." Shakespeare, to go down, must be blended with something alien and more potent.

But someone will object that I am forgetting the Old Vic. There we are told, the "great heart of the people" beats nightly, at the cheapest prices, to every play of Shakespeare in turn— the whole caboodle, in fact. Well, I have never been there to see. For one thing, like the balloonist in Mr. George Ade's fable, I dislike crowds. For another, the Old Vic is out of the way, in a squalid slum and on the wrong side of the river. But one may understand whit is happening, though one keeps one's respectful distance. South London, a dreary, ugly district, inhabited by dismal, prosaic people with starved imaginations, repressed desires and half-baked culture, has discovered Shakespeare! So the B.B.C. (the

British Broadcastin g Company) have lately brought Mozart and Beethoven by wireless into every back shop and attic in the country, which now listen to real music for the first time. Let the professional reformers and philanthropists, the social propagandists, the boomsters, the boosters and uplifters and the rest of the busy-body mob make the most of these facts! They demonstrate, I dare say, that the world is being made if not safe, at any rate sweeter, for Democracy; but I do not see that they affect the position either of Shakespeare or of Mozart and Beethoven. They are facts that belong rather to tables of cociologic statistics than to the history of taste.

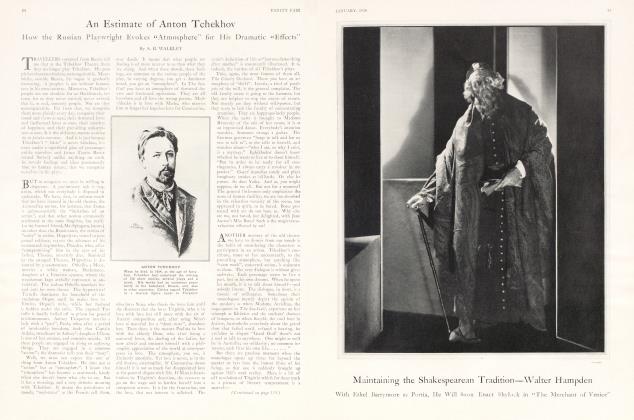

What keeps Shakespeare alive in the modern theatre, is less a popular demand, the desire to hear him, than an individual "urge", the desire to act him. He was at his Zenith in the period from mid-Eighteenth to midNineteenth Century, say from Garrick to Macready. It was, conspicuously, a period of great acting: after Garrick, the Kembles, the Siddons, the Keans, Macready and Phelps, chiefly of tragic acting; for it was a twobottle, inflammatory, sentimental and lachrymose, emotional, demonstrative, blustering (and, on the whole, rather vulgar) age; the very age for the buskined magniloquence and roaring passions of tragedy. When women swooned and shrieked, and maudlin men blubbered over Edmund Kean, Shakespeare (the child of a very similar age, two centuries earlier) came into his own. Today, I suspect we should regard Kean as a ranter; but the great histrionic tradition associated with Shakespeare still obtains. From the tradition has been evolved a standard test, a kind of class list. Every actor ambitious of first class honours must "give his proofs" in Hamlet or Macbeth or Othello. We know these parts by heart, and are curious to see what his "reading" of them will be, and to compare him with his famous predecessors. So long as there is an art of acting, so long shall we see, over and over again, a play or two of Shakespeare. The rest we shall read in our study—on a wet day when the gramophone is out of order.

A. B. Walkley

The Distinguished Dramatic Critic of the London Tin.es Contributes a Monthly Article on The Theatre Exclusively to VANITY FAIR

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now