Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowA Chinese Curio Hunt

An Incident, Vividly Dramatic, of Life in the Foreign Colony of Pekin

PAUL MORAND

EDITOR'S NOTE:—This story, A Chinese Curio Hunt is by Paul Morand, the French novelist and poet. It is the first of a series of tales of the Orient which M. Morand will write for Vanity Fair. A Chinese Curio Hunt, although undoubtedly legendary in incident, gives an exceedingly interesting account of the picturesque diplomatic colony in Pekin at the time of the outbreak of the Great War in 1914.

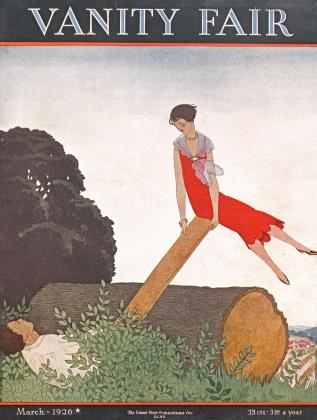

MARION ALDER BEAUMONT, known as Queen MAB—thanks to the initials on her travelling bags—is the blondest woman in Pekin. The Chinese say that her hair has a softer glint than the uncombed silk of Fokien. She is the capital's most sought after lady; she holds all records as a recipient of masculine attentions and European dinner invitations. She is the widow of an English silk merchant and a widow such as few dare to be now that there are so many "divorcees"—a widow, with a vengeance. She has a happy egoism, an ease in her solitude, an insolence in her liberty which completely turn the heads of those very men who might attempt to resist her.

The English naval attache is mad about her; the Collector of Customs would smuggle for her; the Minister from Russia would prefer her hand in marriage to an appointment as Ambassador to the court of St. James.

Under the July sun, at three o'clock in the afternoon, her rickshaw carries Marion Beaumont across Pekin. Her foulard dress flutters in the breeze. The coolie's bare foot touches gingerly the burning asphalt pavement of the Foreign Legations' quarter—that asphalt which seems to remember its birthplace in the volcano. The rickshaw passes the great, heavy iron door, pierced by machine gun slits and topped with the inscription: "Lest we forget", which dates from the events of 1900. Here is barbed wire. Here, on the ancient skirmishing-ground, stretching as far as Hatamen, only tennis or polo balls now whistle. There are no more wars. Men have become good. . .

WHEN she reaches the real Chinese part of the city, Mrs. Beaumont stops her private rickshaw before a curio store. The art dealers of Hatamen have shops next door to each other extending in endless array, so that entire quarters of Pekin seem one gigantic trading house. The overpopulation of China! Where, in France, there would be one little old man in charge of a palace full of treasures, here there are a dozen huge, half-naked men to haggle with you and sell you a tiny "Ming" bibelot,— made yesterday, of course, in Japan.

Mrs. Beaumont, however, does not enter any shop. She sends away her coolie, feigns a moment's interest in the window-displays, then walks off, briskly; the wind blows hdr dress and outlines, amid its transparent folds, her arms and legs, revealed through the light material as by an X-ray.

Oscar Stein arrived in Pekin early in the spring of 1914. He was a Dane, a bachelor, rich and a lover of art; and he had come to make private excavations in the Province of Hanau. On the entire face of the earth, the city where social events are most noisily discussed is neither Syracuse, with its whispering cave of the tyrant Denys, nor yet Rome, the European capital of gossip. The world's stormcenter of small talk is Pekin. You have barely exchanged your tweed coat for a dinner jacket, before the wife of the Chinese Financial Adviser knows how many strokes you took to go around the golf course; in the club, at the cocktail hour, the Minister from Bulgaria warns you (how does he know that such and such a merchant has paid you a visit?) that you have, in his opinion, paid too much for that screen; across the fruit and wine the director of the Gunnau Bank reproves you for inducing his stenographers to partake of insidious drinks with intentions less pure than the gin. Everything is known, and the little that is not known, is invented. People are ignorant of nothing save (if they are attached to a legation) of Chinese politics.

Thus, one hour after his arrival, so handsome a man as Oscar Stein could not fail to be pigeonholed. Simultaneously, on the polo grounds, in the swimming pool of the United States Legation and over the Club bar, it was whispered that the Hotel dcs Wagons-Lits harboured a guest who was not only the best ballroom dancer in Pekin—versed in that new evolution, the tango—but a remarkable archeologist to boot. Oscar Stein presented a few letters of introduction, and, since a scientist so young and bearing so close a resemblance toAntinous, had never before been seen there, he created a furore. Pekin fears every contagious disease, save love. Rockefeller Institutes abound. Who will endow the. world with clinics for affections of the heart?

Two months passed swiftly by and the Chinese summer, less luminous than the winter, arrived suddenly from the South, in the guise of great, romantic storms and pompously bewigged clouds. Oscar Stein had not, so far, been credited with any dulcet adventures. He managed to give the impression of being difficult and treated each "salon" of Pekin with the same strict neutrality. He amused himself and drank, neither falling in love nor into his cups, whatever the youth of the lady or the age of the bottle. Ever on the point of leaving to begin his excavations, he announced himself detained in Pekin by the dilatoriness of the Chinese government in granting him the necessary permits. One by one, the ladies of the legations left Pekin; some headed for their temples in the Hills, others for their villas in Peitaho, still others for the more modest hotels of Haikwan, at the foot of the Great Wall. (The Great Wall, for small purses.)

"You know my darling Mab, that I can't ever do without you. But I must leave. It is absolutely imperative. Only for a few weeks. This month, this terrible August, so many men in the world have abandoned what they love— and for reasons far more serious than mine—I am only a neutral. I have never fought— really fought—except for you. Be mine, Mab." And Stein proceeded to clasp his arms about Mrs. Beaumont. . . .

AUGUST 28th, 1914. Already a month of war in Europe. Pekin, frivolous Pekin itself, developed huge emptiness which seemed funereal. Typewriters rattled in the Chancelries; but the banks were without business. Tennis courts had become drill grounds. Without displeasure, the Chinese learned that the whites were butchering each other. Thanks to these exceptional circumstances the loves of Oscar Stein and Mrs. Beaumont enjoyed an unprecedented secrecy.

After leaving her fine white rickshaw, Mrs. Beaumont had engaged a public one—a rather dirty conveyance dragged by a perspiring coolie with plaited hair and naked red torso. Jolted —elbowed by porters, who balanced as on the trays of a weighing machine the merchandise with which they impeded the traffic—sprinkled with the water which fell on the roadway from the creaking wheel-barrows of passing carriers —the merry widow pursued her course through the sordid, ruined and malodorous city. It was the rainy season and the rickshaw had to find fords through the overflowing drains; once, in passing, it spattered with mud the white silk robe of a Chinese dandy, the colour of green wax, carrying out for an airing his favourite bird in a little gilded cage hung with porcelain angels; again, it disturbed frantic transactions which, from having started with deprecating smiles and murmurs of "I am unworthy, I am unworthy" behind the bamboo portieres of shops, were breaking off in the gutter amid mutual imprecations. Only the dogs remained undisturbed —dirty, indifferent Pekinese, .so tough that no one any longer dreamed of eating them—some, reddish black, others a soiled beige, sleeping exhaustcdly in the mud, without troubling to wag so much as the tip end of a tail when Klaxons shrieked around them.

Continued on page 90

Continued from page 44

At the end of the street rose at last the outer wall of Pekin, baked by centuries of sun like an ancient Corean pot, with its high doors topped with pointed pagoda roofs.

No Chinaman turned around to stare at Mrs. Beaumont, or ask himself what this European woman was doing in these distant quarters at an hour when her compatriots were either eating lunch or enjoying a siesta. She stopped before a handsome red lacquer door, fastened with a brass bar, which was cut into a wall, green and mouldering with dampness. The door opened, revealing one of those tortuous passages, sharply bending and intended to baffle hangers-on (with evil intentions) who might attempt to slide in behind visitors. This path ended in a courtyard, with large bay windows opening out under a jutting roof. Ancient western houses and Chinese buildings offer curious analogies.

Stein, dressed in glossy black silk Chinese trousers, tightened at the waist without a belt, stood waiting. Not a "boy" was visible. The entire quarter slept under the weight of the sun—it was the glowing night time of the Extreme Orient. Crickets chirped metallically.

"My love!" -

Stein was holding Queen Mab in his arms. Her body warm—like

a loaf of bread just removed from the oven—as if consumed with the intensity of the nervous life which emerges from the dry, electric air of Northern China. She allowed herself to be led across a second court, deeper in shadows, more secret than the first, from which the sky was invisible and where the interwoven canes, like jungle bamboos, allowed only narrowblades of fire to filter. On the ground lay Ammonite mattresses, made of black oil cloth and unrolled like manuscripts; there were pillows, hard as a log of wood, which hurt the back of the neck; and a rug of Mongolian cat. On a low table, there w-ere some dusky drinks.

Mrs. Beaumont was in love for the first time. Like many other Englishwomen, she had been satisfied with being beautiful, isolated in her own beauty as on an island, and was accustomed to regard men as "necessary evils." Used to the Extreme Orient, where white women are a rarity, she judged love harshly—that is to say, she viewed it with her tongue in her cheek—until the gods avenged themselves by sending her Oscar Stein. Then, although her own brilliance had until then been safely insulated; although she had been in the habit of considering matrimony as a monstrous business arrangement and the rest of life as an improvised and absurd picnic—Mrs. Beaumont fell into the trap and was caught, at the very time when she least expected it.

"My dear, don't go away. It's so short a time since I first came to you here! Just after the war began— hardly a month. Do you remember?

I thought you were staying at the Hotel des Wagons-Lits. You were driving the car—How surprised I was when we turned off Morrison Street and only pulled up after going through the Gate of the Drum! Ah! This little house beneath the trees, these lotus flowers in their jars, these winged fish with their goggly divers' eyes, these paved courtyards and this roof, so covered with grasses that it seems likely to collapse under the first rains—they are, henceforward, my whole life." Thus spoke Mrs. Beaumont.

"Secret streets of Yamen, sombre paintings like old tobacco leaves touched up with vermillion, twisted tile roofs,—all of these are the tribute of the East to the most beautiful of the beautiful. I offer all this to the woman I keep for myself and will never relinquish. And the war, which is separating the whole world, is uniting us." Thus spoke Oscar Stein.

He took Mrs. Beaumont in his arms and made her sit close to a table which held a green tea set, with plates full of lotus seeds, fresh, white and hard as nuts. He set the phonograph going. The clatter of the dry wind announced the evening. The western hills, rising blue over flooded fields, made one think of the Euganean Mountains beyond the Venetian lagoons—"like wings of earth folded in evening sleep" they showed between the trees, those trees growing so densely that sometimes Pekin seems an inhabited forest.

As Mab rose to go, Stein confessed that he was leaving Pekin that same evening.

"Mab! Don't rob me of my strength. I must go to Hanau. I have received my permit; only the local authorities are still making difficulties. They're waiting for a bribe. Nothing can be done until I go to settle the matter."

"Not now, darling. You haven't the heart to leave me. Think of the plains of the Marne, of the Mazurian lakes, where hundreds of thousands of men are already rotting, forever separated from their loves. Oh! look—"

Mrs. Beaumont shivered. A huge Chinese crow hovered through the air with a strangled, implacable cry, so startlingly addressed to her that it seemed a warning from destiny. He circled around them with his flat wings, ruffled at the tips like an old feather duster. It was one of those crows that are to be seen from Pekin to Moscow, one of the crows of Asia —Asia, the mother of all cadavers.

"Shall we be married when you return?" asked Mrs. Beaumont suddenly, as if fixing a date and taking such a decision might arrest the flow of the great river of sorrow and forgetfulness.

Continued on page 92

Continued front page 90

"That would be the deepest happiness that could befall me. I leave-to-night for Shanghai where I'shall pick up my scientific instruments—get them out of the customs. Then I have two weeks on horseback—In a month, at most, I shall be back."

"Don't go."

"For a little while."

She looked at Stein. His eyes gave the lie to his last tender words; thev had become hard; she felt his will keyed to a purpose.

A flash crossed her mind. ,

"You are not leaving—you are not going to the war?"

Oscar Stein smiled.

"I am a 'sale neutre' ", he said in French.

"Swear that you are not going to enlist."

"I swear it."

Mrs. Beaumont melted for a last time in the young man's arms. He held her in his hands like a tree's heaviest and highest fruit which one hesitates to pick because it is the finest.

One evening, Mrs. Beaumont was returning from a ride to the Temple of Heaven. Above the Wall, a bleeding sun shone through a spatter of violet clouds. He had been gone a month without once sending her news. Dromedaries, laden with munitions for the Russian troops, crossed her path. They looked stupid and pretentious; their winter coats clung in clusters to their haunches, like old, moth-eaten rugs. He had not given a single sign of life. But, yes:—some American friends, the day after Stein had said he was leaving for Shanghai, had met him in the Kalgan railway, heading for the North—Why had he lied to her?

That night there was a dinner at the Russian Legation. The "boys" in their white tunics, impassive, looking absent-minded but paid to hear and understand everything, were passing black and gold lacquer finger bowls.

Every conceivable evil had been said of one's neighbor. Only between allies, however. Then, in thought, those who were absent were brought under fire.

"By the way, who has news of Stein?"

No one had any.

"Will he return with some new steps, that extraordinary dancer?"

"Probably only another adventurer," concluded the Belgian military attache.

"My dear Minister, why always find flaws?" Mrs. Beaumont could not refrain from observing, with a blush.

"Dear, beautiful lady, that Dane with his scientific mission, that Dane who was unknown to his own Legation, never impressed me very favourably, if you care to know what I really think about him."

"Perhaps we shall see him return in the uniform of an officer in the Uhlans," said a diplomat, with all the jealousy of an inferior dancer. The Russian minister smiled wisely.

"His Excellency, our friend and host, looks as if he knew a good deal more about it than any of us," remarked a French secretary. "What does he think?"

After dinner, when the ladies had retired to the drawing room, the diplomats present gathered in the Russian minister's study. There was a Frenchman, an Englishman and the Belgian military attache. Cigars were passed. It was the intermediate season and black dinner coats alternated with the last of the white mess jackets. The Europeans, holding fans in their hands, had a falsely Asiatic air.

The talk ran on curios. One of the men specialized in collecting rugs, another weapons, a third lived only for monochrome paintings.

"As we are between ourselves, I will show you a very rare piece," said the Russian minister, drawing a key ring from his pocket and unlocking his strong box. He pulled out a package, done up in Chinese silk. Slowly, with his red, gouty fingers, he undid a double knot. On the top of the package were some papers.

"It must be a valuable 'bibelot'— it travels with a pedigree," some one remarked. "The Chinese always have identification papers for their fine pieces, giving the names of all its different owners—"

"This object has belonged to only one person, and if I don't open the parcel wider, it is because I want you to digest your dinner peacefully. This object, I say, belonged to that same Stein of whom we were speaking a moment since. It is his head."

Under the yellowing papers, covered with sand, could be discerned a black mass, mummified by the dryness of the desert.

"Stein was an officer of the German General Staff, a spy," continued the Russian. "We learned this, thanks to an intercepted telegram.—His orders were to go to the region of the tunnels near the Baikal lake, and blow up the Tran-Siberian Railroad. We warned some faithful Mongolian tribes that he was on his way there. As a sign of submission and loyalty, the chief of the clan has just sent me, by special messenger, the head of our impeccable dancer."

"Might we see what his letter case contains, my dear colleague?" queried the chief of the British Secret Service, Major General Sir Erik B. . . .

"Quite impossible," answered the oblique Russian, with a smile "You would find in it the photograph of a lady who is dining here tonight— One of our fairest friends, and perhaps most celebrated for her virtue. And after all, of such women there are far too few—in Pekin."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now