Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Shameful Shameless Lady on the Stage

"The Green Hat", Now on Tour, Will Reach New York Next Fall

ALEXANDER WOOLLCOTT

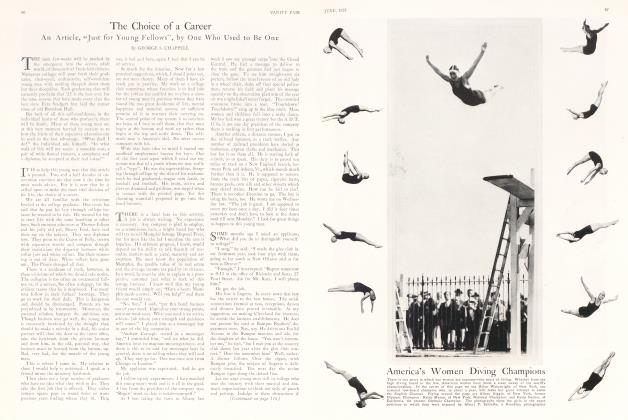

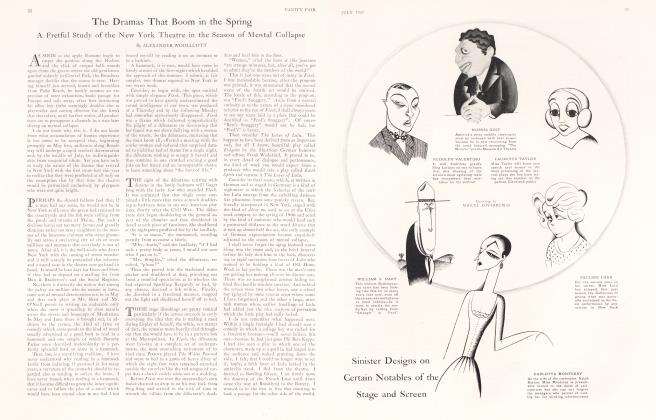

IT IS a temptation to begin with a few words to the effect that, the stage being what it is, our Katharine Cornell has come to where you sec her now by a series of somewhat forced Marches. One of these, a rough hearty girl from America with flat heels and billowing poplin skirts, she introduced to the London playgoer long ago. The other, a quite different and very English lady in a green hat, she will play in New York when the fall comes again and the bells ring up the curtains for another season on Broadway.

The first, of course, was Jo March, for all the changes and chances which have been Miss Cornell's portion in the past half dozen years stem from the night in London when an English actor named Allan Pollock saw her playing Little Women in his home town and knew that she was good. The other March is the shameful, shameless lady who is the heroine of that most marvellously wrought romance by Michael Arlcn from which he has now fashioned the four act play you will be dragged, not unwillingly, to see this fall.

THE not inconsiderable difference between these two heroines—the Jo March who let the ink fly in her stern effort to forget the handsome lovesick lad next door and the Iris March who kept getting into bed with the strangest gentlemen in odd corners of Europe in her groping and not conspicuously successful efforts to forget her yearning for her lad next door—is not only a measure of Miss Cornell's variety. It measures, too, the things the recent years have done to all of us. It counts, gallon by gallon, the water that has flown under the bridge.

I have already seen Miss Cornell's performance in The Green Hat. Having betaken myself to Chicago for reasons which now escape me, I found that city and the neighboring Detroit (which the passing play had left in a state of considerable and unwonted flutter), all humming with talk about the romantic piece Master Arlen had fashioned from his novel. And, as you walked down Michigan Boulevard under its unwinking lamps at night, you would be stopped by perfect and imperfect strangers wanting chiefly to know how closely Miss Cornell approximated the Iris March whose defiant green hat bobbed bcckoningly through the pages of the book. And it need hardly be added that you, in your evasive way, said thus and thus.

For my own part, as I mulled over the book, the fell lady with the tiger-tawny hair had the half-closed eyes, the frosted look and the silvery sheen of Diana Manners, with just a faint something of Irene Castle in the cool jaunty eloquence of her shoulders and the fine set of her lovely head upon them. I doubt if the dark, glowing radiance of Katharine Cornell comes anywhere near the outward seeming of the Iris March who took form in the mists over Michael Arlen's head as he spun his tale. I know that she is utterly unlike the portrait with which I, as a reader, had illustrated the book. And I am at some pains to record that fact here if only for the high privilege of recording also the fact that I do not think it matters a hoot. As Miss Cornell plays the role, the spirit of Mr. Arlen's luxurious daydream comes true. She understands the character utterly and it is in her to find tokens and voice for the ache and the gallantry of that hungry heart. If I set down a suspicion that she is scarcely the type Mr. Arlen had in mind, it is for the pleasure of adding: "What of it?" She is just about as much the type as Duse was when she played the Norse mystic in The Lady of the Sea. She is just about as much the type as Mrs. Fiske was when she played the puzzled, hot blooded peasant girl whom Hardy had in the back of his head when he wrote the talc of Tess.

THE play, as has been said, is of Mr. Arlen's own fashioning. The theatre has taken hold of him and set him to work. He is to make a play out of These Charming People for the autumnal uses of Cyril Maude, who had laughingly said that he would retire after Aren't We AH? He is to make another play out of The Cavalier of the Streets for Robert Milton—which is a bit of a joke on the frustrated Guy Bolton, who had talked of doing it himself. Then he knows the sweet taste of the impressario's profits for, across a luncheon table last spring, Arlen casually advanced the negli-

gible number of pounds which made possible the production in London of that huge success, The Vortex, which Noel Coward, who wrote it, will himself play in New York in September. Also he and Frederick Lonsdale have jauntily agreed to foot the bills whenever Arthur Hopkins is minded to show London how good a play is What Price Glory? Finally, the guileful Arlcn has signed contracts to spin sundry romances for the movies. All this, mind you, in the immediate future. I do not sec how he can do much punting down Datchett way this summer or loiter over his tea under the awnings at Marlowe. I do not see how he can hope to biff off to many shooting boxes between now and Michaelmas.

THE play which Arlen has made out of The Green Hat shows no surprising irreverence for the details of that romance as he had first conceived them. But considerable simplification of manner lets the story flow directly through the four acts. The first of them is not, as you might have anticipated, set beneath the brooding elm tree where the interfering and deluded Sir Maurice once sent Iris and Napier into the world, each on a separate path. The play begins a little later at that shocked hotel in Deauville on the morning when the dead and crumpled body of Iris's bridegroom is found on the flagstones beneath the windows of her room. Thus you are eavesdropping when she faces them all that day and swears that Boy Fenwick died "for purity".

The next scene is the eve of Napier's wedding when his path and Iris's cross unexpectedly and fatefully. The next, of course, is the hallway of that chill convent hospital on the edge of Paris, peopled with the veiled and hooded nuns and the little French doctors "with cold eyes and purple beards." It is also peopled (at the cost of some breathless panting on the part of the inexperienced playwright) with all the other characters of the play until I, from my seat in the second row, began to wonder if this hospital hall was not like the terrasse of the Cafe de la Paix. Just let me sit here long enough, I said, and I shall see every one I ever knew. Finally the destinies of the Arlen puppets converge in that fine dramatic scene at the Harpenden library and the curtain falls at last when the ochre roadster crashes into the elm tree down the lane.

As for the green hat, itself, perched there on a lady's head, it is just a reminder of the book. And once in the play it looked to me a little like something else. Hilary had come back to Napier's house in Mayfair in the chill hours of the morning. He had rooted that harried young man from his bedroom and there were anger and disdain in his friendly eyes. For there -was no use in Napier's pretending that Iris had gone home. The Hispano Suiza still stood at the curb below and there, lonesome and accusing on the couch, lay the little green hat which she had taken off pour le sport. And for the space that a breath is held it looked to me less like a hat than like a fan—a fan that used to be wafted gently in the drawing rooms of the middle nineties. It belonged to Lady Windermere.

(Continued on page 92)

(Continued from page 41)

A breath is held a good many times in the course of The Green Hat, for there are several scenes of true and beautiful suspense, several scenes where the speech and the understanding glow with a distinguished beauty. Some of the play-building is gauche and artless and I think it gives evidence of being the work of a man who has not yet found himself in the theatre, who has not yet had the courage to use his own idiom throughout a play. It is so with these authors when they first step timorous through the alarming stage door. It was so with Barrie, who had to write several plays in imitation of his predecessors before it dawned on him that it would be no bad idea if he were just to write a play like Barrie.

The Green Hat is the work of a young man who has said of himself "I am only half-heartedly a realist and may yet live to be accused of shuffling humanity behind a phrase". That utterance, which will be found somewhere in The London Venture, constitutes as fine an example of understatement as contemporary letters afford, with the possible exception of that stirring moment when the husband of Melisande kicks her several times around the castle only to elicit from her such an inadequate comment as: "I am unhappy".

Such a young man has written a play, fashioning it on the outline of a fine, glamorous romance of his own telling and boldly letting his characters don the cothurnus of newminted, lovely Speech—speech as remote from the true talk of the realistic theatre as are the inverted monotones of Pelleas or the lyric rapture which leaps from Romeo under the balcony in the Capulet garden.

"When I look at you," cries Napier, enchanted on a Mayflower rug at midnight, "it is as though this world, this England, the laws and the land of England, fade and pass from me like phantoms. They can't be phantoms, Iris."

"They are," she answers in her desperation, "they are, they are— cruel, bullying phantoms."

"Yes," he goes on, "and when I look at you, it's as though everything but you was unreal. Who are you? You're Iris, my first playmate, and then you're Iris, a woman with magic eyes and a soft white body that beats at my mind like a whip. It's as though you came from an undiscovered country, where the men are strange and strong, where the women wear their souls like masks on their faces and their souls know not truth nor lying, nor honor nor dishonor, nor good nor evil. In the land you come from Iris, the women are just themselves—towers of delight in the twilight of the world. Iris you are a dark angel."

Which suggests, by the way, that Alien only loaned Guy Bolton the title of that play and suggests, too, that when the author calls himself a halfhearted realist, he is indulging in a wild exaggeration. He's a tenth-hearted realist. And since it is an idiom which no other playwright is trying to employ in this drab and sooty day, and since beauty and truth and glamor can be the fruit when such a scene is played by such players as Miss Cornell and Mr. Howard, I trust Mr. Arlen will seek and find a technique of playmaking and decoration that will sound his warning note from the rising of the first curtain and not leave any playgoer laboring for one moment under the suspicion that after all he may have come to see a piece by Mr. Galsworthy.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now