Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowIn the Path of "Pauvre Rachel"

ALEXANDER WOOLLCOTT

A Comment in Retrospect Upon the Failure of Rachel in This Country, as Compared with Duse's Triumph

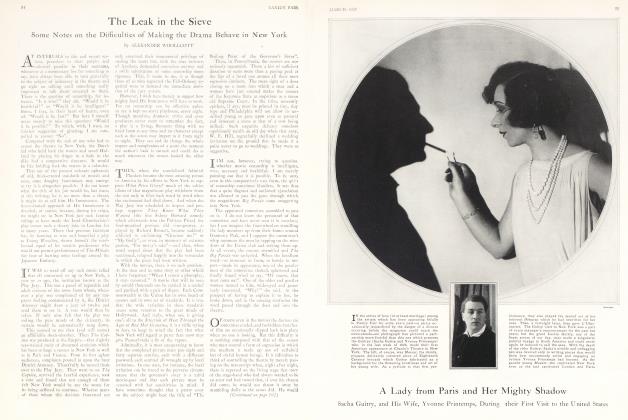

DUSE has proved a t rouper. Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington, Chicago, New Orleans—these came after New York. And then—since she was following in the footsteps of Rachel, she moved on to Havana, where the first and last American tour of the great French tragedienne went finally on the rocks. But for the fragile, exquisite old actress from Italy, one who on her return to us was of such frail aspect that her very shawl seemed too great a burden, Havana was but a wavstation. Back she sailed to New Orleans, and moved on to Los Angeles and San Francisco, which most of our own players never reach at all. So many of the younger ones are quite prostrated by the thought of touring as far as Philadelphia.

Duse's management, in luring her westward, took the precaution to include the well known climate of California among their blandishments. There would be orange trees in flower on just, such fair and sunlit hills as cup her own city of Florence. Her response suggested that she had more human interests.

"Perhaps", she said eagerly, in the tone of one who is all for packing the old trunk at once, "perhaps thev will let me meet Mary Pickford."

Her spring schedule called for a jaunt through the midland cities—Cleveland, Cincinnati, Detroit, and the like. Then Boston, of course; and, by way of farewell, New York again. Somehow a study of this formidable route brought suddenly back an afternoon in the June before Bernhardt died. Some of us were calling on her in her cluttered, raffish, old house in the Boulevarde Pereire. In a room all flowers and afternoon sunshine, there she sat, withered and jaunty, a mutilated but gayly clad ancient who was, of course, abrim with plans for a return to America. But, she added ruefully, she was too old, too tired for one of the long tours. Just New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington, Cleveland, Chicago, and a fewr such places. But not a long tour.

Rachel's Ambitious Program

THE energy of Duse's tour has been no more astounding than the readiness and the wholeheartedness of the American response to her unspent magic. In auditoriums too vast, with penurious scenery and a sometimes paltry repertoire, the greatest actress of them all has held our people spellbound. She is playing in an America somewhat changed from the one in which Rachel's ambitious tour came to so abrupt and so melancholy a conclusion.

That tour was undertaken seventy years ago. It was Rachel's brother, Raphael Felix, who kept enticing her with promises of a vast fortune to be made out of the gaping savages across the Atlantic. Even to this day, if the Guitrys ever come to us. it will be for that alone; and there is not a French player alive who believes that American approval would add a cubit to the stature of his artistic reputation. The argument appealed especially to one whose anecdotal history bristles with tales of ravenous greed. But even the contract promising her 1,280,000 francs (plus hotel expenses) would probably have failed to lure her to so remote and barbarous a land had she not been furious at the acclaim with which Paris welcomed the art of her rival from Italy, the great Ristori—acclaim which appears to have been somewhat guilefully fomented. At least, Mr. Dickens wrote home to the folks that he had seen the flowers which had been impulsively hurled at Ristori's feet after the first act being sneaked back into the auditorium, so that they could be hurled there again at the end of Act Two.

A French Artist's Reception

A GOOD many factors served to keep Rachel's American receipts considerably below the level on which she had counted. A good many mishaps served to impair her enjoyment of the tour. From the very hour of her landing, little things went wrong.

For instance, her ship came in a good ten hours before it was expected, to the immense irritation of the Lafayette Guards, who had chartered a launch to go down the bay to meet her. It was to have been a mixed party. According to the New York Herald of the next day (August 23, 1855), "large numbers of enthusiastic females had been occupied for weeks in training their laryngeal organs to enunciate the French language correctly, and were anxious to know if Rachel could polk, and was she pretty?" Others of a more practical turn of mind, who remembered the Glen Cove regatta, where 1500 persons were fed on a pound of corned beef and three boxes of crackers, anxiously inquired if there would be anything to eat. "This party, resplendent with uniforms unstained by war and gay with flounces and bonnets and bretelles, assembled at noon only to hear the newsboys in the streets shouting: 'Extry! Extry! Rachel's come, and Sebastapol ain't taken.'"

Then, the prices proved a little dismaying. The best seats were, flagrantly enough, four dollars each; and this in a day when one dollar was the price usually paid only by the more squanderous—a day when, according to all the historical economics we have learned by attendance on costume plays, eggs cost two cents a hundred, plumbers worked from dawn till midnight for fifteen cents, and bricklayers just didn't, charge anything at all. Certainly, the Rachel prices left unused tickets each night at the old Metropolis Theatre, where her first performance was given before an attentive but plainly dressed audience. "Although", according to the Ilcrald. "a few people, owning large quantities of jewelry, did dash out a little." These exceptions, however, according to the candid observation of that lively journal, were probably in the trade.

Foreign Reports of Rachel's Tour

WHAT New York looked like to Rachel, already exasperated by the fact that the Lafayette Guards came nightly to her house at 5 Clinton Place to demand that she sing the Marseillaise, can best be gleaned by a glance at the account of the tour which a minor member of her troupe, Leon Beauvallet, wrote with great gusto and some acerbity for the Figaro, back home.

"The houses are literally covered with immense placards. From the cellar to the garret, you see nothing but highflown advertisements, colossal canvasses, and monstrous bills, all ornamented with huge figures of men having nothing human about them, imaginary animals, and a thousand other representations made solely to draw the simpletons and loafers of two continents into the shops.

(Continued on page 102)

(Continued from page 54)

"And can you think what all this makes the city look like? A gigantic handbill of a mountebank company. These are here, also, as well as with us. Broadway, the Boulevard des Italiens of this place, is inundated with them. Quacks, dentists, breeders of learned dogs, exhibitors of branded negresses, wild beast tamers, all are in abundance. One could fancy himself in the fair of an immense village. What a hubbub! what tumult!

"Cries and laughter, songs and oaths; the yells of newsboys, mixed with the noise of carriages; the trumpets of charlatans, confounded with the bells on the mules who drag entemally, on the thousands of railroads which furrow the streets, trains of cars, thirteen feet long, like ours. Add to all this, carts which get locked together; horses running away; the people one crushes; the loafers to fly from; the drunkards who are being ill-treated, and all the loungers in white vests, who parade at the doors of hotels, smoking gravely, their heads down and their feet in the air. Do not forget, above all, the hundreds of prostitutes, with large hands and feet, false teeth, painted cheeks, sunken breasts, who encumber the sidewalks, in the very face of policemen and the sun, and you will have a very small part of the picture which New York presents to the bewildered eyes of the traveler 1"

Rachel's Repertoire

THUS speaks Mr. Beauvallet, considerably embittered, it is true, by the price the bus driver charged for taking him over the cobblestones to his hotel in Broome Street, by the vermin with which that hotel was infested, and by the fact that Rachel was the only member of the troupe of whom America seemed aware. But his notes reveal a strange city for a showman to select as likely to be enraptured by the fossil tragedies of Racine and Corneille.

Rachel, you see, was the first player from overseas to challenge America in a foreign tongue. And on her first night, Rachel, standing in the wings for her first cue in Les Horaces, was first puzzled and then stricken by a swishing, rustling sound, as of wind moving through underbrush, as of rain on a steel helmet. The greatest actress of her time had to play her first scene in America to a sea of downturned faces, to the incidental music of turning pages. Every one at Les Horaces was dutifully reading a translation. When, the other day, a certain bewilderment marked the somber countenance of Helen Westley during Frau Triesch's performance of Rosmersholm, history was repeating itself. Explanations in the lobby unearthed the fact that Mrs. Westley, while willing enough to be impressed by the German actress's art, had thought she was attending a performance of The Master Builder. And one old gentleman at Rachel's first performance, having brought a translation of the wrong play, was led out into the night under the impression that he was losing his mind.

A Comment Upon the Barbarians

IT was when Rachel returned to New York after the Boston engagement that the relations became most strained. On this return visit, she played out at the Academy of Music, so remote from the center of town that one had to go there by mule train. And all New York's vanity had just been rasped by the latest packet from Paris, which brought over Jules Janin's appeal in the Journal des Dtbals for her return from the barbarians. In impassioned paragraphs, he asked her to desist from desecrating the classics of French tragedy by presenting them before black and white audiences of bloomer-clad women and whistling, lounging, whittling men.

"For", cried Janin, "though they resist Iphegenia, though they go to sleep before the furies of Orestes, though they call Corneille stupid; yet, at the beck of Barnum, they rush to see a stuffed mermaid; or, seated in her filth and her drivel, an old, black, idiot mummy, whose hideous teats suckled the great Washington! And these heroes of equality, though they believed the old woman to have been really the nurse of their great man, their saviour, not one of them thought of snatching the poor old thing from the hands of the showman. Say to Frenchmen, on the contrary, 'Here is the mother of Voltaire', and they will fall on their two knees before her. Rachel must already have felt, and every day she will feel it more keenly, that it is she who is the barbarian, because she is not understood. Soon she will, I trust, leave the country to the bears, the streetpreachers, the tumblers, the Barnums, and the usual amusements of the American people."

The Difference Today

IT was to a sensitive New York, made sulky by this famous article, that Rachel was then obliged to play; and, soon after, having given but 38 of the 200 performances called for by her contract, she harkened to Janin's cry' and, from Havana, sailed at last for home. "Pauvre Rachel!" murmured Bernhardt when, a quarter of a century later, she, too, sailed for home after the triumph of her first visit to America.

Since then, the players of all lands and tongues have found the way easy in America; and this very season troupes have played here nonchalantly in French, German, Yiddish, Italian and Russian. Nay, our stage has grown so frankly polyglot that Duse's bland performance of a Norwegian tragedy in Italian for a patient American audience was immediately followed by the Moscow Art Theatre's performance of an Italian comedy in purest Russian. The dramatic critics, those once carefree lads, trot now from theater to theater with a small stack of books under each arm, wearing, one and all, the harried look of the schoolboy who has too much homework.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now