Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowSome Program Notes For Ruth Draper

An American Phenomena Who is an Entire Art Theatre in Her Own Person

ALEXANDER WOOLLCOTT

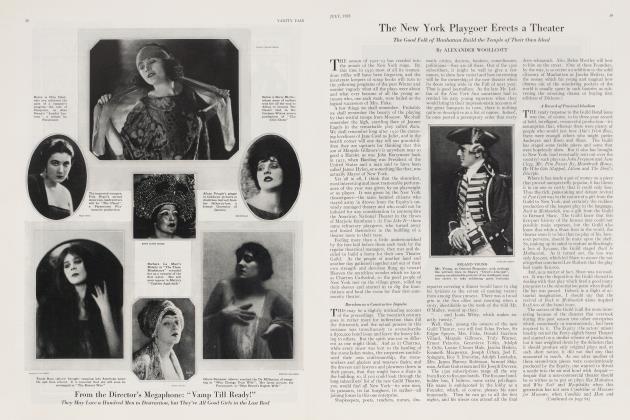

A PACKED theatre humming with expectancy, an empty, muted orchestra pit, a stage hung with curtains but bare of furniture except for a single chair. Without preliminaries, a lean, dark woman somewhere in her thirties walks stiffly on. This is Ruth Draper on her way to work.

She has a sudden, brilliant smile and just the faint suggestion of a Spanish ancestor lurking about her somewhere. She glances almost imperceptibly over the crowded auditorium as if wondering where on earth all those people came from. Next she bows—a formal, starchy little bow full of an ugly threat that she is about to recite something.

Then abruptly, without any trick of lighting or face-paint, with no properties or shenanigan of costume beyond, perhaps, a shawl to throw over her head, she turns before your bewildered eyes into some one else. And then some one else. And some one else. A New York debutante, perhaps, rattling away at a dance. Or a French dressmaker bamboozling a helpless American matron. Or a thin-voiced squire's lady playing guide to the herbaceous borders of her garden in Kent. Or a Dakota woman cutting wedges of pie for the travelling salesman at a station lunch-counter.

And as the spell begins to work, it takes a conscious effort of your mind to remember that the salesmen are not really there bantering across the pie, that the harried Mrs. Guffer from whom the hostess in that English garden plucks the exploring caterpillar is not actually sharing the scene with Miss Draper. In the sketch she docs of the young Philadelphia mother escorting her four recalcitrant progeny to a children's party, you not only develop a faint distaste for any one so ostentatiously competent in the management of tots and kiddies. You not only see the four rebels themselves, but the stage becomes populous with the whole rambunctious swarm of youngsters raising hell in that distracted house, which stands (unless my ear for dialects deceived me) somewhere in Germantown a trifle to the west of Main Street.

IT IS an endless pageant of creation, each figure startling in its truth, each uncannily accurate in the finest distinctions of the American language. For Ruth Draper knows that the speech of Madison Avenue, New York, for instance, splits into two dialects about half way up the street and that a quite different language is spoken behind the austere blinds of Rittenhouse Square a hundred miles to the south.

Her gift at self-starting impersonation, her knack at all the familiar wiles of what is known in the two-a-day as the "proteen artiste," is so dazzling that it has, I think, obscured and delayed the recognition of her more remarkable gift. I am speaking of Ruth Draper as a writer, which she is of course, although, as it happens, she fashions her dramatic portraits aloud without ever committing them to paper except afterwards and for purposes of copyright.

Whoever gave birth to that "Italian Lesson" (the only successful capture in contemporary art of that faintly fabulous creature, the New York society Woman) and whoever wrought that State of Maine crone (the one that takes her twilight half hour of vacation from her husband's sickroom, by rocking on her verandah and, in her discourse, saying more about New England than most writers can get into a full-length novel)—whoever wrote these things belongs I think in the great company of William Dean Howells, Willa Cather and Mr. Tarkington.

Now that Ruth Draper is recognized by the public as an indisputable institution like the Philadelphia Orchestra or any other recurrent boon, I detect in other gazettes a tendency on the part of even the critics to discover her. If this process has been a trifle lethargic, perhaps there was some discouragement in the fact that it is not easy to report her. There is, you see, no ready vocabulary wherewith to describe her. The words "recital", for instance, and "monologue" had horrid connotations. In Life recently Mr. Benchley spoke of her as a "diseusc," a lamentable term and one I myself have avoided nervously ever since the New York Times employed it to describe Miss Rosalind Fuller and was betrayed by its own composing room in the embarrassing plight of having described her as a disease.

Then she has no exact forerunners to whom one can hitch her. In a London journal recently, E. V. Lucas went way back to the late Charles Mathews (died 183 5) for her precedent, though 1 myself think one comes nearer the matter in the readings (which were not readings at all) wherewith Mr. Dickens used to hold vast audiences enthralled. Glance, if you will, at the letter Carlyle wrote home on April 29, 1863. One passage read:

"I had to go yesterday to Dickens's Reading, 8 P. M., Hanover Rooms, to the complete upsetting of my evening habitudes and spiritual composure. Dickens does it capitally, such as it is; acts better than any Macreadv in the world; a whole tragic, comic, heroic theatre visibly performing under one hat, and keeping us laughing—in a' sorry way some of us thought—the whole night. He is a good creature too, and makes fifty or sixty pounds by each of these readings."

But, after all, I think it also dawned slowly on Miss Draper, herself, that this gift of hers was sui generis, an art form and a career in itself, no mere symptom of a talent, no mere indication that she was due for triumphs as an actress on Broadway or, let us say, as a writer of short stories, but was itself the thing in this world she was clearly meant to do. At first, and for a long time, even after her name had begun to take on a little lustre in her own land and day, no such notion possessed or animated her.

SHE had drifted into it quite casually. It all began, I have been told, at a house party on Jekyll Island.

"And, my dear, we'll get up an entertainment," said someone in the ghastly fashion of such conclaves, the inevitable someone, who, whenever convenient, should be carefully assassinated on the eve of every party.

This time the ensuing program is not a matter of record. Who firmly sang The Gyfsy Trail (followed, I suppose, by a brave assault —nay, battery—on Temple Bells) who metrically and painfully confessed to being less of a man than Gunga Din, who fetched a saw from the woodshed and laughingly played a tune upon it, I cannot say. But when Miss Draper's turn .came, she walked on in the manner of Beatrice Herford, whom she had seen and admired, and with a knack for mimicry which she had always had about the house, there reproduced for the other guests the look, the manner, the tone, the idiom, the very flavour of the little Jewish tailor who occasionally invaded the Draper household armed with pins and tape measure.

Continued on fage 104

Continued from page 43

Thereafter the invitations to do him again and more like him came thick and fast—for charity bazaars, at parties, at Miss Spence's school in New York and the like. Small wonder that Miss Draper thought of it as a kind of macaroon for society to nibble at. Ahead of her, if she thought about it at all, she must have seen just spasmodic repetitions of this uninteresting pattern—her little parlor stunt duplicated endlessly to the gloved applause of a mannerly audience seated uneasily in semicircles of gilt chairs.

It was Paderewski who led her aside on one of these occasions.

"But my child," he said, "I see something much bigger for this. I see great distant cities. I see long, patient queues at the box-office and acres of motor-cars parked outside the theatre where your name is in the bills."

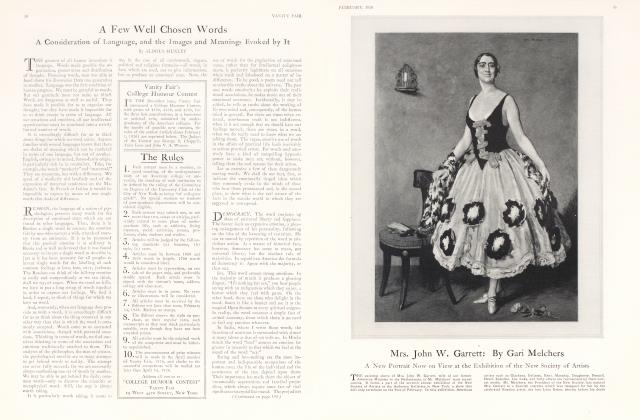

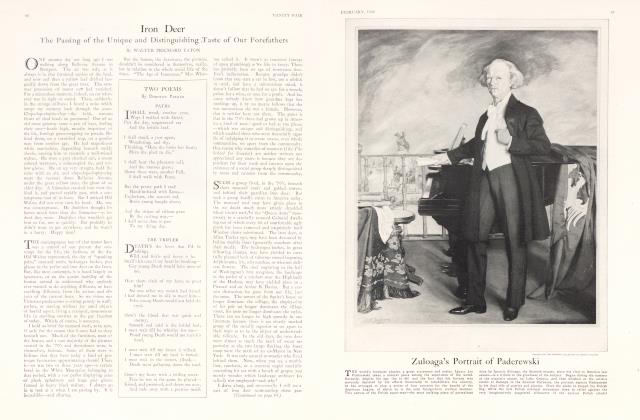

At which mild prophecy, Miss Draper went into gales of innerlaughter, wondering, I suspect, if the mighty virtuoso had gone out of his mind. Yet now when her name goes up on the bulletin board beside the door, say, of the Academy of Music in Philadelphia, that vast and draughty temple is packed to the doors. And when, a year or so ago, she stepped off the train in Madrid and walked into great posters which, in flaming capitals proclaimed her as "LA MAS ILUSTRE ARTISTA DE LA AMERICA DEL NORTE" and when, after her season there, she boarded the train again, her kit bulging with the only Spanish doubloons any American ever took by conquest, I hope she gave a thought to Paderewski back in that drawingroom long ago.

It w'as after she had served her turn in the Y huts of the A. E. F. (despite a widely induced notion to the contrary, there were others engaged in this work beside Elsie Janis) and had appeared before the King and Queen of Spain in London, that the outburst of editorial excitement about her in the London papers drove her into the conviction that this was the row she was supposed to hoe and hoe it she should to the end.

Before that, I think, it had always been in the back of her mind that she would "go on the stage," that she would play roles in plays like any other actress. Once, indeed, in a short-lived Harcourt comedy called A Lady's Name, she did play a Cockney parlormaid in the company supporting that ageless soubrette, Marie Tempest. That must have been in 1916., or thereabouts. But she had tried for several such engagements, always to be met by the manager's firm decision that she was not the type. I suppose ^hat in the chronicles of that madhouse, the American theatre, nothing more wildly comical ever happened than the decision that this woman (who, at will, can seem to be a Scotch immigrant girl or a Down East crone or an enrhumee German governess or what have your)—that such a one was "not the type".

It was the late Henry James who admonished her to seek no further than the talent which she held there in her two hands.

"My dear," he said, "you have woven for yourself a very beautiful little Persian carpet. Stand on it."

The kindly James, by the way, was enormously interested in the art of this young compatriot of his. Back in that gritty and perplexing America which he avoided, his father and her grandfather had been friendly neighbors. For Ruth Draper had a great grandfather—the Mr. Dana who forged iri The New York Sun that used to be such a newspaper as we shall not soon see again. Then perhaps James vaguely discerned in her an outlet for his repeatedly discouraged impulse to write for the theatre. He had tried his graceful but unpractised hand at several plays and had suffered the bruising experience of hearing his Guy Domville boohed with simple earnestness by a London pit. At all events he was fired to write a monologue for Ruth Draper, the only one fabricated by another than herself which she ever even tried to learn.

The James attempt was brought by the postman to Miss Draper's lodgings in Cheyne Walk, accompanied by a highly characteristic letter. Speaking of James, Thomas Beer says: "There yet welled on gifted folk those pools of tender correspondence and those courtesies, a trifle tedious, one hears, but rendered with such grace." This pool flowed somewhat as follows:

I am posting you herewith, separately, the monologue stuff that I wrote you a few days since that I was attempting. It has come out as it would or could 5 and perhaps you may find it more or less to your purpose. I don't really see why it shouldn't go: and I seem definitely to "visualise" you and hear you, not to say infinitely admire you very much in it. It strikes me, going over it again, as a really, practical doable little affair; of which the general idea, fortee and reference will glimmer out to you as you study it. It's the fatuous, but innocently fatuous female compatriot of ours let loose upon a world and a whole order of things, especially this one over here, which she takes so serenely for granted. The little scene represents her being pulled up in due measure; but there is truth, I think (and which you will bring out) in the small climax of her not being too stupid to recognize things when they are really

Continued on page 114

Continued from page 104

put to her—as in America they so mostly are not. They are put to her over here—and this is a little case of it. She rises to that—by a certain shrewdness in her which seems almost to make a sort of new chance for her glimmer out—so that she doesn't feel snubbed so very much, or pushed off her pedestal, but merely perhaps furnished with a new opportunity or attribute. That's the note on which it closes; and the last words will take all the pretty saying you can give them. But I needn't carrycoals to Newcastle or hints to our Ruth; who, if she takes to the thing at all, can be trusted to make more out of it by her own little genius than I can begin to suggest.

The monologue thus heralded proved an amusing and subtle one about the self-propelling American matron arranging brusquely for her presentation at the Court of St. James's, arranging it with a tapping foot and a mounting eyebrow as if to say to the harried and unaccountably laggard secretaries at the embassy: "My good men, what do you think we pay you for:" If you would read it, search the files of the London Mercury, for Mr. Squire published it in 1922. The thing was written with no conception of the economy of words Miss Draper practises, no appreciation of her unequalled capacity for implication. She did learn it and I believe she even recited it for James. But it has found no niche in her repertoire. And after all one doubts if she could be at ease with any material that did not have its origin within her own observation. She could no more be happy using one of Beatrice Herford's monologues, let us say, than she could be in using one of Beatrice Herford's toothbrushes. A Draper performance—to filch Lawrence Gilman's rule for similes —must be as self-sprung as a beard.

Why any one should be less than content with such a gift as hers is and such an outlet for it, I cannot imagine. Her independence is complete. She needs no stagehands, no orchestra, not even a theatre. For I have heard her hold a ship's company entranced in the dining saloon and when, for the first and only time in the 113 years of its history Hamilton College broke down and in 1924 gave a degree to a woman (Ruth Draper is now a Master of Arts, if you don't mind), she was able to rear her theatre on the speakers' table at the commencement dinner with no more burdensome preliminary than permitting Elihu Root to give her a hand up and perhaps kicking over a salt-cellar or two.

Yet the old discontent still works like yeast within her. It takes the shape now of seeking new fields, rather than new forms. London, Paris, Madrid, these followed the conquest of her own home town. This winter she is invading Texas. And in the spring—well, it would be no great surprise if April found her playing in Rome.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now